Facts & Arguments is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide.

Well, I thought, just the other day, it’s official. At the far-too-young age of 56, I have become an old fuddy-duddy. And the strangest thing about this life-altering realization is that it came to me as I was thinking about fishing.

I have enjoyed the sport of fishing for as long as I can remember. There’s even an oft-repeated bit of family lore about how, when I was a toddler, my dad gave me a toy fishing rod and reel made of plastic, complete with ordinary household string for fishing line, in order to distract me while he went about the real business of fishing for bass in the other end of our rowboat.

And, of course, you can guess the ending: When Dad finally looked away from his own undisturbed line, he saw that I was in very real danger of being pulled out of the boat by the monster bass that had somehow swallowed the bit of meagre worm on a rusty fish hook that Dad had tied to my string. My equipment, as no doubt advertised on its packaging, was not up to reeling in a real fish, and Dad had to pull my three-pound-plus largemouth in hand over hand.

When I think now about the essence of fishing, it is to those first outings with my dad and my brothers that I return to. They were stripped-down, low-tech affairs: a rowboat that had to first be bailed with a rusty can; bait worms that we dug ourselves while swatting away mosquitoes; short rods with simple reels for the boys and a longer rod for Dad, equipped in later years with what we thought an uncommonly extravagant Garcia Mitchell reel.

There were clear rules, too – though I don’t remember ever being given the full list. One had to be quiet while fishing; the fish, it was well understood, did not like talking and would rapidly evacuate talk-infested waters for quieter spots. What little talking was allowed was almost entirely functional in nature: “I got one,” “I broke my line” and “Please pass the worms.”

But ours was never a sullen boat. We were all very happy, bound together in our common – albeit quiet – pursuit. And the quiet enhanced our connection with our natural surroundings. We could feel the gentle ebb and flow of the water, see splashes and swirls on the lake’s surface as unseen bigger fish pursued shiner minnows and hear birds in the trees on shore. There was also a strong esprit de corps as all but the lucky fisherman who “had one” were required to bring their lines in immediately and help with the landing of the fish (although truthfully, we watched as Dad netted the fish – but only when it was sufficiently played out not to make a sudden surge that could break the line).

Over the years, a great body of stories accumulated: “fish stories,” if you must. Such as when my older brother caught a large bass that actually jumped into the boat while Dad tried to net it. Or a fishing spot so unfailingly reliable that it was known only as the Hole. Or Big Fred, a bass so wise that, night after night in the very same spot, he would take our bait and then escape beneath dense layers of seaweed from which we could not dislodge him without breaking the line.

It is to these wonderful memories that I compare the modern fishermen (I suppose I should follow the CBC and say fishers) that I see on the very same lake. Often, I am awoken early by the thunderous start of Armageddon, only to realize that it is the unbridled roar of a 200-horsepower bass boat arriving at 80 kilometres an hour to fish nearby. Inevitably, it will be joined by other overpowered, undermuffled boats in a kind of muscle-car reunion at the local drive-in.

I am aware that many of these memories are now half a century old and that evolution mandates that both fish and fishers must “evolve.” But can it really be that the bass species, with its former need for absolute quiet, has so evolved as to now have a strong attraction to the blared strains of Bruce Springsteen and Nickelback?

Communication between fishers has similarly changed. No longer is talking only on an as-needed basis. Now, it is constant – a veritable running series of verbal tweets providing moment-by-moment commentary of every action to their companions – and all others in the vicinity. The unrestrained howls of jubilation that accompany the actual catching of a fish would, in my dad’s opinion, have ensured it was the only fish caught in that spot that day!

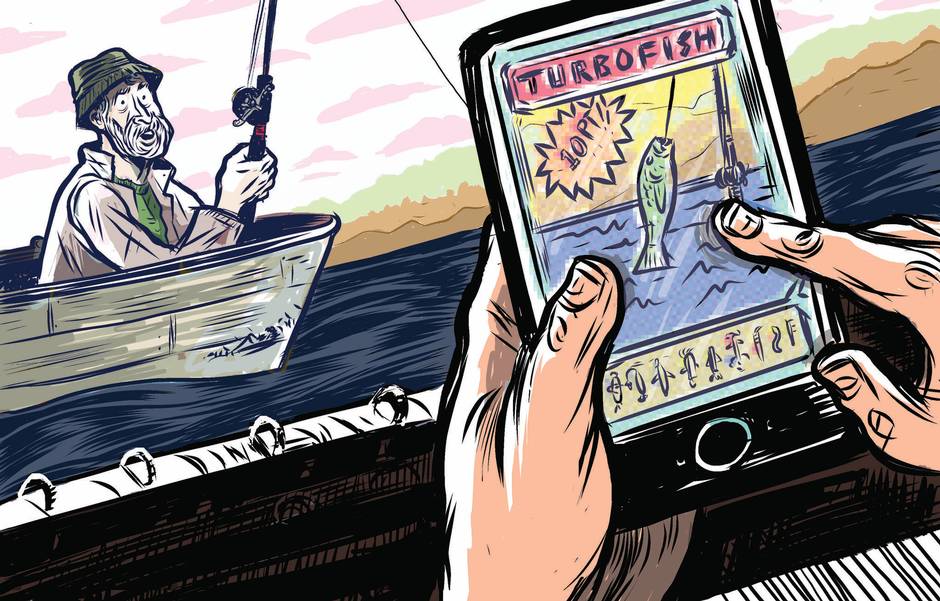

The whole communion-with-nature aspect of fishing also seems to have been lost. To my jaundiced eye, most of these fishers are no longer trying to escape their urban lives for a few hours; they now insist on bringing their urbanity with them. Or is it a new app that alerts of a pending fish strike that these anglers, fishing lines in the water, stare and tap away at so intently on their smart phones?

Lost in nostalgic thoughts, I make my way one evening to my dock to check on my boat. As I step on the dock, I am surprised by the sight of a trio fishing quiet as mice just offshore. A father, son and grandfather, I think to myself. “Beautiful evening,” the father calls to me softly as their fancy bass boat drifts silently by. “Yes,” I say to myself as much as to him. Even for old fuddy-duddies like me.

Michael Freeman lives in Beaconsfield, Que.