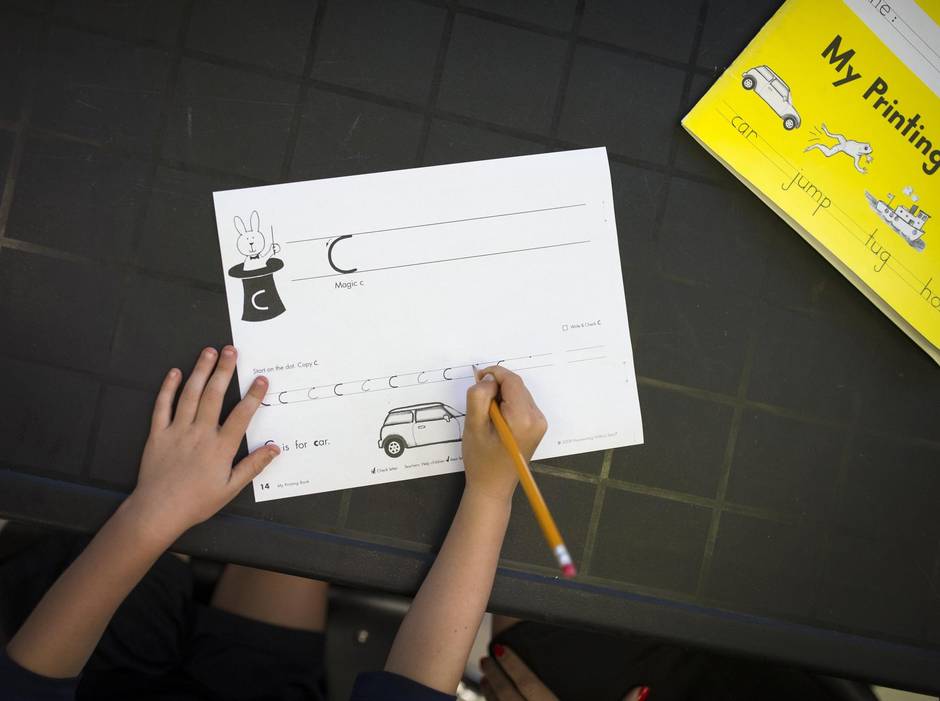

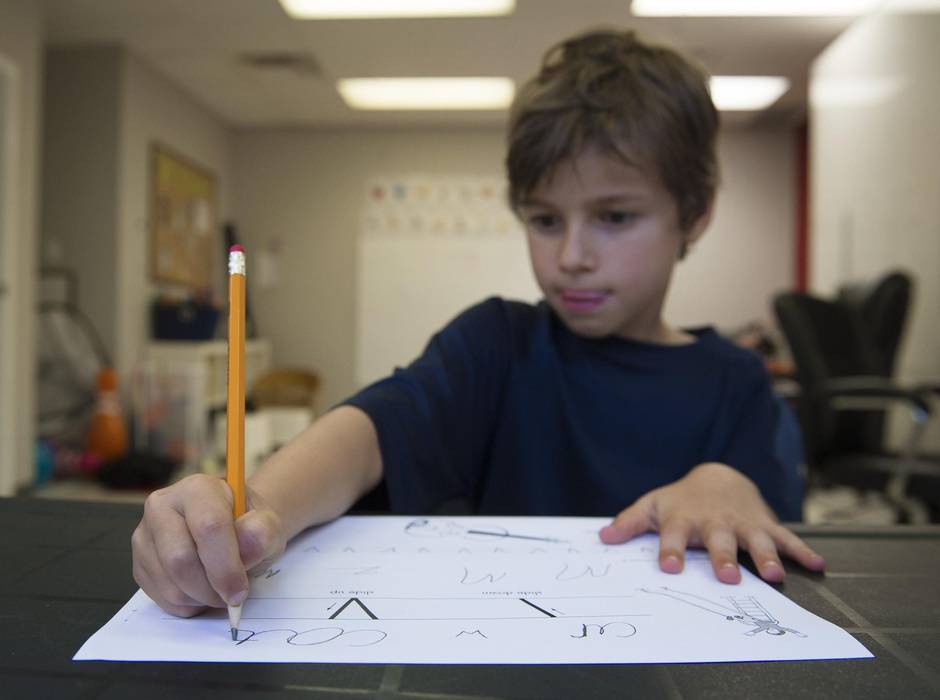

With a pencil still in hand, eight-year-old Mitchell Cait-Goldenthal takes a break from the handwriting exercise he’s working on to explain why it’s important to have good penmanship.

“When you’re older, if your writing is sloppy for something really important – like if you’re playing Major League Baseball and you’re writing your contract – and you don’t know how to write, people might not understand what you’re writing,” says Mitchell, who is taking a class at Ruth Rumack’s Learning Space in Toronto. I don’t tell him that any such contract will probably be typed. After all, he’d still have to sign it.

Considering the pace of technological change, there’s no guarantee any of us will use pens or pencils a decade from now. It doesn’t take clairvoyance to know that in many people’s eyes, pencils already look like feather quills compared to keyboards and touchscreens. Schools around the world are either minimizing time spent teaching cursive writing or eliminating it altogether as a relic, arguing there are more important skills to teach students in the 21st century.

Not all of us, however, are willing to write it off.

Sandra Wong enrolled her daughters, eight-year-old Felicity and seven-year-old Chloe, in a new cursive writing class last month at Wonder Pens, a store in Toronto. “I see it as an opportunity from two vantage points,” says Wong, a health-care manager. “Academically it’s inspiring because it will help them with learning, but it’s also a lost art.”

She’s not alone. Wonder Pens co-owner Liz Chan says the class for kids was created after parents kept asking if children could attend the store’s calligraphy classes. There were approximately 10 kids in that first class, who spent an hour learning to write letters with the same shape – think a, c, and d – in flowing script.

“The kids we get in our handwriting class are just printing. They have no real concept of how to form cursive letters,” Chan, a former elementary school teacher, says. “Just teaching the idea that you form it all in one stroke was a little bit new. For kids who are just learning it, they need a lot more time.”

The time needed to teach cursive may explain why it’s being marginalized, if not outright ignored, in public schools. South of the border, at least 41 states do not require public schools to teach cursive writing. Finland made headlines around the world last year when it announced that cursive would be dropped in favour of teaching typing as of 2016.

Here in Canada, the trend is following the same direction. In Quebec, cursive is no longer an expectation in the curriculum. In Ontario, it’s still on the curriculum from Grades 3 to 5, but individual teachers say they often don’t have time to teach it. It’s not on the syllabus in Halifax and earlier this year, a Winnipeg school asked parents if teaching looping letters should be dropped (more than 90 per cent said it’s a skill still worth teaching).

Cursive is still a staple at private schools and many parents turning to Wonder Pens said their interest wasn’t purely aesthetic. Chan says that some parents expressed concern that as cursive becomes less of a priority in public schools, good handwriting may become a marker of a higher class of education.

Toronto kids can also learn cursive at Ruth Rumack’s Learning Space, an academic coaching and tutoring company in Toronto. “For a number of students we see, their handwriting is an issue,” Rumack says. “It really goes deeper than just legibility of writing. It goes in to self-esteem and academic success. If you don’t have legible handwriting that’s definitely going to hamper your ability to be a productive adult.”

Mitchell’s parents began sending him to the Learning Space in 2011. “He’s the youngest in his class, so we wanted to give him that extra boost,” his father, Howard Goldenthal, says.

The boy likes to write – he’s already penned a book about zombies at the Learning Space – and improving his handwriting has helped him express himself according to his mother, Cheryl-Anne Cait. “You need to be able to get your thoughts out,” she says.

Even if the importance of good handwriting diminishes with every text sent and emoji searched for, legible cursive is still an important mode of communication. There is nothing like getting a handwritten note, says Wong, who believes that it’s personal in a way e-mail will never be. It’s a big part of the reason she wants her children to learn cursive. “I have a very strong interest in the beauty of penmanship,” she says.