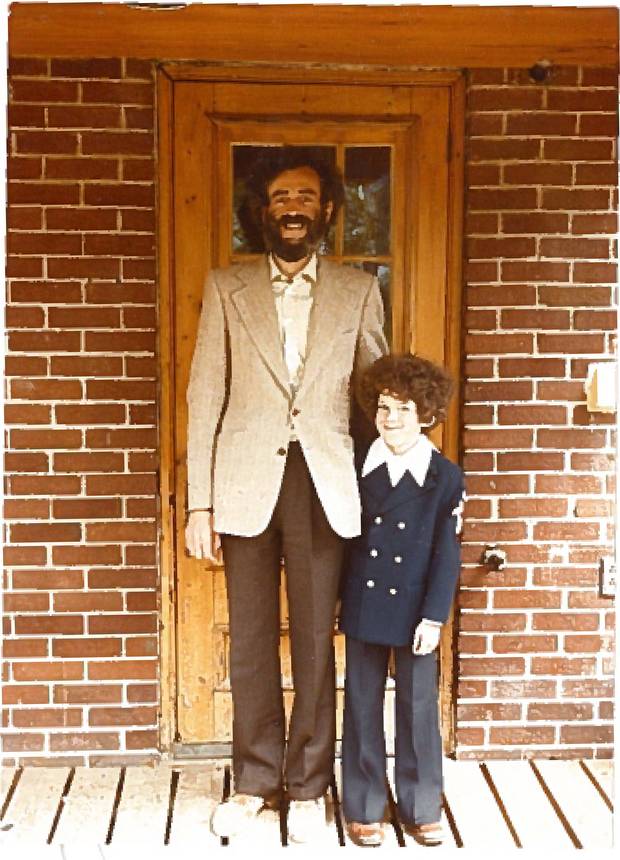

Peter Brown and Ian Brown.

Ian Brown

I now resemble my late father so closely that my wife jumped out of her skin a few months ago when she walked into the den and found me napping with my mouth agape in a rocking chair. It was a chair my father once owned, the same chair he used all his domesticated life to watch "the golf" and "the tennis," a chair in which he too napped, mouth open, and I guess the resemblance, given that he died four years ago at the age of 98, when I was 58, was a little too close for my spouse's comfort.

"It was a glimpse of my life to come," she said, "a reminder that we too are going to get old."

I suppose the balding doesn't help, and neither does the fact that both his and my nose have been broken and bent. We have the same eyes, the same coloring, the same terror of personal finance. Why wouldn't I resemble him? He was my father. I would like to have inherited his patience and self-control and decency as well, but that part didn't stick so firmly.

So there is a part of me that feels proud and lucky when someone tells me how much I am like my father. I feel kinder and cleaner and more content with the silent, subterranean sacrifices being a father entails.

But another part of me wants to run screaming from the room, because of the parts of him I disdained when I was younger: his passivity, his self-defeating caution where all risk was concerned – the very domesticity that made me and my siblings possible. This is what is supposed to happen, of course. A good father teaches his kids to be independent, whereupon they don't need him anymore and leave him. (Which is why "Happy Father's Day!" is an oxymoron.) With any luck he forgives them, and himself. Mine did, I think. I won't be unhappy if I come to resemble him that way.

Shane Dingman and his sons.

Shane Dingman

My dad used to love chasing me and my sister around the house with whatever our cat dragged in (one time it was a dead bat with only one wing). He would make insane noises and play act as if the poor creature was going to get us. I had the dual feeling of incredible exhilaration and revulsion as a kid as I ran screaming. Now, whenever I find a headless rodent or fallen bird (we have neighbourhood cats and birds of prey nearby) I feel this welling desire to torture my boys in the same way. Admittedly, this is the worst, but I love it when they collapse helplessly laughing and yelling. To date, my wife has vetoed this urge.

Joseph Gonda and Gabe Gonda.

Gabe Gonda

I was an only child and my parents separated when I was 10. Until I was 14, I would go back and forth each week between their apartments. I had a close relationship with my father, a philosophy professor who was born in France during the Second World War.

A lot of our time together was spent eating. My father has an intense relationship with food. He's a tall, slender man with a big appetite and he eats faster than anyone I know. This might have something to do with his being born on the run.

His parents were Hungarian Jews who lived in Paris in the 1920s and 30s. When my father came along, in December of 1941, the family had fled the Nazi occupation in Paris and was hiding in Cassis, a small town in southern France, surviving on sardines and condensed milk. After two years, they walked through barbed wire to Switzerland, where my grandparents were separated into refugee camps while the children lived with friends. Eventually the war ended and the family was reunited.

In 1950 they moved to New York City. My father tells the story of eating his first hamburger sitting on a curb in Brooklyn, grease running down his arms. In Toronto, my father and I lived together in a second-storey apartment in a house on Walmer Rd. In the evenings he would cook cheese omelettes or linguine with canned clams. While we ate, I was struck by a habit of his: parting his lips to mimic mine as I lifted forkfuls of food to my mouth. It seemed strange. What was he doing?

I have three boys now and we eat together all the time and sometimes I catch myself doing the same thing.

J. Gilbert (Gib) Adams, father of James Adams.

James Adams

My father had been dead just over 40 years the morning I walked into my sister-in-law's bathroom and saw his face in the mirror.

This was summer, a couple of years ago, while holidaying with my wife in Surrey, B.C. I'd just bowed my head to turn on the taps in preparation for a facial splash. But before I did, I stole a quick upward glance in the mirror and there I wasn't. Instead, there was the face of my father where mine used to be.

Of course, it was my face, just not the face I'd grown accustomed to seeing day after wearing day in the morning mirror. The sensation probably lasted no more than three admittedly disconcerting seconds before habit had me scooping the water running from the tap into my hands and onto my face. My father's face dissolved from mine and down the drain it went – a second dying to follow the first that had claimed him at 54 in 1974. Had the veils of vanity and familiarity, the delusions that make up self-image, I wondered, been permitted to slip somehow, allowing me to see myself as I really was – the double of my father?

A few minutes later I was in the kitchen mentioning the moment to my wife and her sister. "I saw my father's face on someone else today," I said. "Mine."

There was general agreement something weird had happened, then the conversation moved on. The experience, though, stayed with me. It seemed, well … Freudian somehow. (My wife likes to say everything's Freudian to me.) And, sure enough, I remembered reading many years earlier an episode Freud recounted of being on an overnight train trip. He was getting ready to sleep when he noticed an individual in a dressing-gown and nightcap coming towards him. Freud didn't like the man's appearance nor the fact he seemed on the verge of entering his compartment. Within seconds, however, the father of psychoanalysis recognized the figure he was about to repel was none other than himself, reflected in a full-length mirror.

What, I wonder, will this Father's Day bring? The return of the masque of my father? Or my familiar face turned suddenly strange?

Simon Kiladze and Tim Kiladze.

Tim Kiladze

About a decade ago, when I was still living with my parents, I caught my mum peering out the kitchen window looking a little perplexed. She'd spotted my dad doing yard work wearing faded blue jeans tucked into big rubber boots, with a cigarette hanging out the corner of his mouth. In disbelief, she turned to me and said: "Can you believe I married that?"

It was a joke, of course. But by then my dad had been mocked so frequently by my family we wondered what ran through his head. Like the time I caught him typing 'www.bostonredsox.com' into the Google search bar because he didn't understand how the Internet worked. He was lovable, but lived a little in his own universe.

His no-frills lifestyle especially used to irk me. In high school I devoured George Orwell and Margaret Atwood; he read the Toronto Sun. When I bought him nice clothes for occasions like Father's Day, he'd turn around and wear my fancy golf shirt out in the garden. And every Monday evening growing up, he made spaghetti with Ragu sauce for family dinner.

Sometimes it felt like he and I were in different orbits. I've got my mum's long and lean frame, and stand about 6 foot 3. My dad's 5 foot 8. We've also got different demeanors, which fuelled wars between us. He promised to quit smoking when I was about eight years old, but soon broke the pledge. I was so upset about his weak willpower that I took a key to the driver's side door of his 1977 Corvette. It is a miracle I'm still alive.

And yet, as I age, I feel his gravity pulling me in. Before my wedding two summers ago we went for a tasting dinner at our caterer, a Toronto BBQ joint called Barque. As we sat together eating baby back pork ribs, my dad casually mentioned he used to work there. We laughed; he wasn't kidding. The restaurant was on Roncesvalles Avenue, which used to be the main strip for Toronto's Eastern European immigrant community. He worked at a butcher counter roughly where we were sitting.

Turns out I can be pretty practical too. My husband has an affinity for nice things, and we bicker because he would love to own an Audi one day. Until it broke down in May, I drove a 16-year-old Mazda Protégé. My baby lost her power steering during the last year of her life, but I trudged on, because why waste money on a car? My dad always preached, 'They only get you from point A to point B.' Somehow that's stayed with me.

His food choices also stuck. My downtown friends mock me for happily eating at Boston Pizza, a chain I've grown accustomed to from family dinners there in Mississauga. My dad happens to like the beef dip. On weeks when I'm too lazy to grocery shop, I've proven capable of sustaining myself eating white pasta with nothing but salt.

There's more. My dad had some health scares over the past two years, including suffering a stroke. (Those damn cigarettes.) He's recovered fully, but the ordeal made me reflect on what he instilled in me. There are the frivolous things, sure, but in subtle ways he taught me there's no substitute for being there as a father.

When I broke my jaw playing football, he was standing on the sidelines and took me to the hospital screaming like a banshee in the passenger seat; when I started work at Tim Hortons at 6 a.m. in high school, he'd always wake up to drive me, in exchange for nothing but a free coffee; when I needed a ride to McGill in undergrad, he'd journey six hours to Montreal and back in a single day.

He isn't an openly emotional guy, so he'll never quite say why he was around so much. I can't help but think it had something to do with the fact that his own dad wasn't. My grandmother was Polish and my grandfather was Georgian, and they fled Eastern Europe when my dad was an infant in 1946. So close to freedom, they got caught at the border crossing into West Germany. According to various versions of the story I've heard, my grandfather allegedly paid the border guards to let his wife and son through, but was forced to stay behind, and possibly sent to Siberia. My dad grew up never knowing what happened to him; it wasn't until he was roughly 30 years old that he found out his own father was alive.

Growing up I was a keener with highfalutin aspirations, dreaming of careers that would demand long hours or all my energy. My dad's enduring presence has re-configured them in monumental ways. The act of always being there, no matter the career cost, now resonates more than I'd ever imagined it would.

Paul-Emile Leblanc and Daniel Leblanc.

Daniel Leblanc

When I think about what everyone likes most about my father, I always go back to the words of wisdom that he offers to those who seek his advice. He has a knack for listening and allowing people to determine the best course for them to chart. I'm not sure I have those abilities, but I do try to pass on the philosophy that he instilled in me to my own children. When I tell them "Do your best" and "What is worth doing is worth doing well," I'm simply repeating what I heard as a child. My father has a way of eliciting the best in all of those around him, which is good path to try and follow.

Sonali Verma, second from top right in white, with her father, Rajanikanta Verma, bottom right.

Sonali Verma

When we first got to know one another's parents, my husband and I often joked that the worst-case scenario is that, over time, he turns into his mum and I turn into my dad.

At least part of that is happening.

As a kid, I always wanted to be like my dad. He joined the foreign service after taking an exam that hundreds of thousands of Indians take every year. His rank? No. 1.

His memory is extraordinary. He is loud and funny: I realized only after growing up that our family has more "in jokes" (all created by Dad) than any other I know, rituals that bind us and remind us of what we share. He is a warm, generous host, and holds court as the centre of attention at every single party.

But once I had children of my own, I realised that it is my mum I want to be like – gentle, calm, forgiving, thoughtful, beautiful, gracious and unendingly patient.

And yet, I inevitably find myself walking at a brisk 6 kilometres an hour and having my companions wonder why I am impatient and always rushing (Dad walks like that). I find myself thinking uncharitable thoughts about people I don't like and imputing petty motives to their behaviour and then thinking up retorts that could hurt them in the worst way possible, like he does. And after spending years listening to Dad parse pieces of music on the radio, I now find myself holding forth on music theory while listening to classic rock and pop music with our boys.

What I really want to do is to be able to adopt his outwardly insouciant attitude towards children doing risky things. My dad brought up three daughters in India. And yet, he encouraged us to do things that young women never did – like taking the car to the mechanic – because he never wanted us to have to depend on a man.

When I went to university at 17, I used to ride 45 minutes in Delhi traffic hanging on to the bumper of an overcrowded public bus – and then often walk back part of the way alone, after dark. Never once he did he suggest any of this could be unsafe, though, as a parent myself, I now realise the thought must have crossed his mind. Unlike many Indian fathers, he spoke to me openly about relationships and sex and alcohol, and never with a trace of judgment. When I was a teenager, he encouraged me to study and work abroad, without a word about how hard it would be to find "a suitable boy" for me. The real gift my father gave me was confidence.

Despite some nasty fights, he always believed in me and always went out of his way to ensure that I knew I had his support. Probably because I really am just like him.

Wojtek Bielski and Zosia Bielski.

Zosia Bielski

I started becoming my Polish father in Grade 5 with the arrival of copious body hair. Now, 25 years later, his jowls are slowly taking hold on my face, a saggy pudge that marks the entire Bielski clan. Apparently I also got his legs – "nice legs!" as a female student remarked during one of Dad's high school classes when he stood by the blackboard, his furry but weirdly dainty gams on display.

These troubling physical inheritances aside, I'm slowly warming up to the things my father has always loved, hobbies I resisted hard as a kid. Like "taking the air" by Lake Ontario in January, our faces numb in howling winds, our family completely alone on the beach. Or skiing, enduring those wintry hellrides on the lift, over and over again. Now it's me pushing dad for another tear down the hill before the lifts close, even as his knees are starting to give out.

A lazier inheritance from my father has been his been his habit of cooking, buzzed, to an unhip soundtrack – Peter Gabriel, Shock the Monkey? – that blares from my wood-paneled JBL speakers. They are enormous and outdated but booming, another gift from dad. Slowly, his Neo-Luddism ("the Internet is a portal to hell") is taking root in me: when dinner party hosts crank autotuned, robot-crooners through their iPod docks, I wish I was at my dad's house instead.

More than his wariness toward modern technology, dad reserves his greatest disdain for Big Government and other authoritarian monopolies, what he refers to as "the man." This is probably residue from the daily indignities of life in Communist Poland. I have nothing so oppressive to fight against in Canada but I try to keep Dad's spunky approach in mind when dealing with "authority figures."

But really, I'm a try-hard hoping for more of Dad's freewheeling attitude. Whether he's downing moonshine or cranking up an avant garde-jazz drum solo while we're snarled in rush-hour traffic, the man is unbelievably zen.

A friend at university would explain that you slip into this type of blissful indifference as you age because your neurons stop firing as rapidly. After a certain point, this friend would claim, we are all re-programmed to stop giving a crap. Dad's never given a crap. For that he is my guide.

Mick O’Kane and Josh O’Kane.

Josh O'Kane

I'm pretty sure I was once the youngest bank teller in New Brunswick. It was my first summer job, and I had to tuck in my shirt and never wear jeans and I hated it. As if that wasn't awkward enough, as I walked one day from my wicket to the lunchroom, a man hollered at me from across the branch.

"Hey Mick!," he shouted, his face contorting in surprise as I turned around. Mick is my dad. I was profoundly embarrassed, not because of who my father is but because that mix-up seemed impossible. He was, in my teenage mind, old. I had neither attuned my eyes to nor accepted the inevitability of genetics. It was more than the grown-up costume I was wearing that made my dad's friend confuse us. It was the barrel chest, the giant head, the splayed shoulderblades, a stride more waddle than walk.

It was a long time before I acknowledged just how much I was transforming into Cool Mick. (His friends once revealed his '70s nickname, earned with a popped collar, at a family reunion.) And a funny thing happened as we both got older. The old-dude seriousness I'd attributed to him as a kid melted away as I, too, became a functional adult. We even thought the same way.

When I went away to university, all I wanted to do was live on my own and party and write sarcastic stories for the student newspaper – but also get a job and make lots of money. During our annual drives to campus, the man who once seemed like a serious adult started revealing his real character, cheering me on with a caveat: his catchphrase, repeated ad nauseam, was "work hard, play hard." (This had already been used as the motto for the gay steel mill on The Simpsons, but I never brought that up.)

Cool Mick's maxim played out for both of us: we take our work, but not ourselves, seriously. We have become the same stupid goof. Rather, I became the goof I never realized he was.

Last year, he told me how excited he was at work, managing a growing team he gets to infuse with his work-hard-play-hard spirit. So, after years of him exclaiming, "You the man!" when he was proud of someone, I got him a Yoda bobblehead inscribed with the words "YODA MAN." Now he leaves the bobblehead on the desk of his co-workers whenever they do a good job. And when he wants to congratulate a family member, we get a one-word e-mail: "YODAAA!!!" It's a simple, absurd gesture that distills the lesson Cool Mick wants to impart to everyone: you should strive to be your best self and a complete idiot at the same time.