Artist Robert Genn wanted his home studio to be a place where he could chase his muses, and his children could discover their own. At the centre stood the easel where he painted, a sort of altar, surrounded by creative stations – a Yamaha D-80 console organ, film and photography equipment, a bird feeder, a writing desk, a loft for dreaming and writing stories. Wooded trees surrounded the place; it was not unusual to see eagles nesting. This haven to creativity is where his children – Dave, Sara and James – grew up, learning to be artists themselves.

“We think that if any of us would have become doctors or lawyers, we would have been disowned,” says Dave, a composer and musician best known as guitarist for the rock group 54-40.

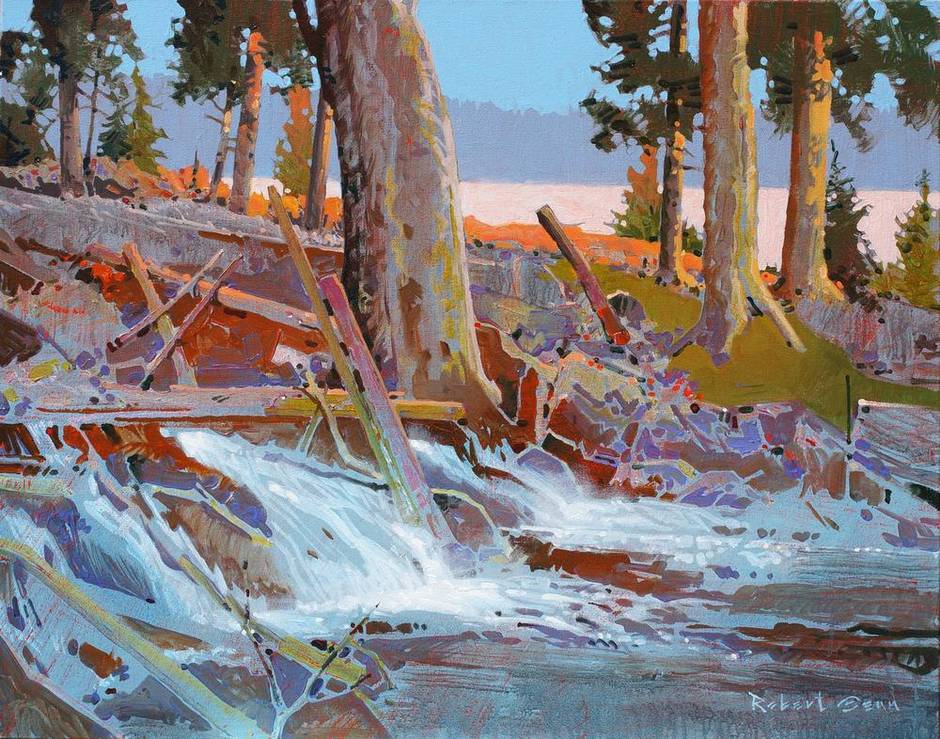

It was in the studio in the Crescent Beach community of Surrey, south of Vancouver, that Robert Genn’s long-time family doctor told him, almost exactly 12 months ago, that he had “perhaps a year” to live. He was 77, married almost 50 years, had three children, three grandchildren, and now, pancreatic cancer. And it was in his studio that he spent his final months, painting and combing over his life’s work – hundreds of canvasses depicting Canadian landscapes, especially the West, and works inspired by his travels. Since his death in May, daughter Sara, a painter and musician who lives in New York, has continued the job: cleaning, cataloguing, wrapping and communing with her father.

“Today I was on the floor of my dad’s studio, a place where I’ve painted my own paintings for decades and lay on the floor as a child while he painted at his easel. And now I’m alone in that room going over his paintings and in a new relationship with him and his imagination and his dreams and his triumphs and every stroke is his heart,” she said in a recent interview, becoming increasingly emotional. “What child has that from their parent?”

This weekend, in an unprecedented collaboration, four commercial galleries – in Toronto, Banff, Alta., Kelowna, B.C., and White Rock, B.C. – will simultaneously open a final Robert Genn show, each selling 15 paintings, selected by Sara.

“It was their idea to do that. They wanted to do it and they wanted to do it together and simultaneously and to make all the work available together,” she said. “It’s not the standard way they do things. And so I see it as a real testament to my dad and the kind of person that he was and the kind of artist that he was to work with.”

A working painter since he was a teenager, Robert Genn – Bob to his friends; Bobby to his mother – was born in Victoria in 1936. According to family lore, he began drawing – drawing well – at the age of three. Around that same age, he was driving through town with his grandfather when he saw “a little old lady sitting on the stool by the side of the road, painting.” It was Emily Carr. “That moment left a little mark on my dad,” said Sara, recounting the story.

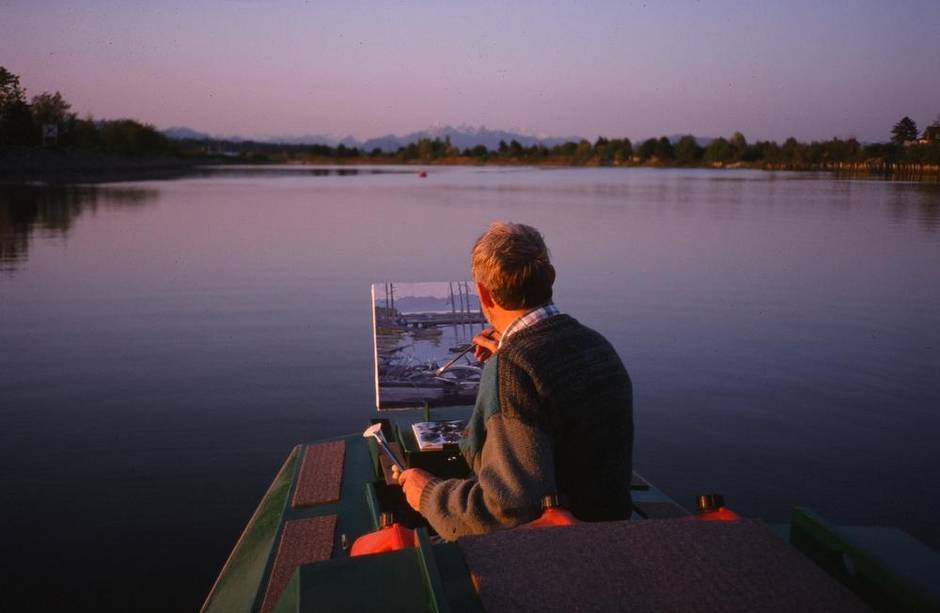

Genn, who often worked en plein air –influenced by Tom Thomson, the Group of Seven and, of course, Carr – painted around the world and kept a rigorous studio schedule at home. He was often there at 5:30 a.m., painting to classical music while his coffee went cold. With this work ethic – and his obvious talent – he was able to make a good living as an artist (and author; he also published several books). He advised his children: “Waiting for inspiration is for amateurs; professionals get to work.”

They all did; in addition to the artistic successes of 45-year-old Dave and 42-year-old Sara, her twin James is a Toronto-based director whose TV credits include Seed and Call Me Fitz. Because they are self-employed, they were each able to put their lives on hold, to some extent, after their father called to tell them the news.

They considered how to spend the time they had left together. There were thoughts of trips to Hawaii or the Galapagos, but Genn wanted to end his life as he had lived it: in his studio, making art, with his family close by. James fashioned a reclining chair so his father could continue to paint, lying down, as his illness took a physical toll. “He made it is his mission to go as long and as far as he could with a paintbrush in his hand, and he was painting small canvases right up until the last few weeks,” James said.

“There’s a thing in the culture that says, if you’re given a year to live, what would you do differently? My dad did the exact same thing in the last year of his life as he had been doing for the first 77 years,” Sara said.

But there was one thing the ticking clock demanded of Genn: He would have to deal with hundreds of works in three storage areas on his waterfront property. He did not want his artistic legacy to include anything substandard.

The difficult task of dividing his life’s work into “destroy,” “sign” or “keep” began the day after his diagnosis, and continued until his final week. It became a final family collaboration.

“He called it sad but fun to go over it all, and to see the experiments and the triumphs and failures and remembering all of our travels – paintings from trips we had taken, and paintings of us as youngsters. … It’s like looking through an album of your life but they’re paintings, not photos,” Sara said. “I’m relieved and glad that I was at a stage professionally, and maybe even emotionally equipped, to really be there for my dad and help him as a partner to cull his life’s work.”

A few weeks into the process, they loaded the van and drove to a friend’s property and threw canvas after canvas onto a bonfire. Multiple trips to the dump followed. “We were pretty joyful,” she said. “We didn’t have that feeling that it was over, but that feeling that it’s his world and his choice.”

Because of his close relationship with his children, Genn was in the enviable position of feeling no need to make amends, share wisdom or reveal secrets at the end. “We didn’t have any of that stuff to do,” Sara said. “I didn’t have to say, ‘Hey I need all the contents of your brain in the next two weeks because I’m about to lose you and you’re really smart, and I have to get some tips.’ … There wasn’t a panic for any of us in that area.”

Genn turned 78 on May 15 and died on May 27 – the twins’ birthday. Sara has since selected 60 works for his final, cross-country, show.

“With those seven months with dad culling the archive, and discussing each painting with him fresh in my memory,” she said, “the paintings were fresh to me, with their stories, their rediscovery, and the place each work holds in the overall oeuvre.”

Robert Genn (1936-2014): Honouring a Lifetime of Painting opens Saturday at 10 am at White Rock Gallery (his widow Carol Genn will attend) and Hambleton Gallery in Kelowna (Sara Genn will attend); at Canada House in Banff at 11 am (Dave Genn will attend); and at Mayberry Fine Art in Toronto at 1 pm (James Genn will attend).