What is community to you? Talking to a neighbour over the fence? Or crisscrossing the country to meet people who've obsessed about bug-eyed pugs with you online?

Community is increasingly being forged virtually, where like-minded individuals can encounter each other in esoteric meetup groups on the Internet and then travel great distances to meet IRL (in real life). They aren't just geeks, but people who are no longer alienated by their interests and who challenge the long-held idea that the Web disconnects humans from one another.

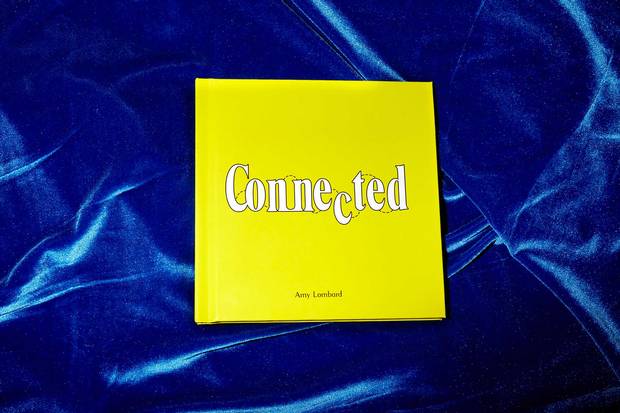

Or so says photographer Amy Lombard, who dropped in on online meetups from Oakland to Orlando for her new book Connected. From gingers to "aces" (asexuals), barefoot hikers to chihuahua enthusiasts, Lombard traces a bewildering array of fraternity. Her conclusion is that the Internet hasn't killed connectivity but evolved it.

Lombard, 26, spoke with The Globe from New York about what hyper-specialized connection brings to people that traditional friendship might not.

When I was in my early 20s using rudimentary social media – LiveJournal! – the idea of an in-person meeting with people you'd only met online seemed nuts. Back then, the Internet felt murky and risky.

It was the You've Got Mail era. I still remember logging onto AOL for the first time, hearing the dial-up Internet. People were talking to people online but nobody was actually meeting in real life. There was a period of uncertainty. I still remember my mom being horrified when I put my last name on the Internet.

I was a misfit kid: I couldn't communicate what I wanted to say in real life. The Internet was my safe space to talk with people. I was gravitating to chat rooms where I could be myself and be accepted. I watched these societal shifts happen over the course of my life: What started off as taboo is now integrated into our daily lives.

There's much hand-wringing over Internet disconnecting us and killing conversation, but your project offers a different lens.

On one side, the argument's definitely fair: you go out to dinner with your friends and everybody is staring at their phone. That can be infuriating. But then I think back to when I was a kid and I felt like such an outcast and going to really specific communities like "Mad Rad Hair" on LiveJournal. The idea of not being accepted, it has changed.

Today, what kind of connection do these online meetups give people in real life?

It changes from meetup to meetup: not every one is butterflies and rainbows. Sometimes it's not seamless socially. I describe it as like going on a date for the first time. Being able to talk with someone online or on the phone and then being able to meet with them face to face is exciting and nerve-racking, too. The jumping-off point is the hobby: there's not much to disagree on.

Tell me about the dads meetup group.

Stay-at-home dads, they're this rare breed that you hear about and you know they exist, but you don't always see them. So to see them walking single file down the Highline in New York was such a sight: 40 dads with Baby Bjorns, it was amazing.

They talked about diapers, clothing, what parks they go to. It was a way to bond over these things and perhaps the stigmas, too, the connotations people have about them. They were all very progressive and very blunt: their wives were lawyers or doctors and financially it didn't make sense for them to go to work, leaving their wives to stay home. It was cool.

What about the asexuals' meetups? Were they less open?

When it came to photographing this community, it's still a bit of a touchy subject. We've come so far with the LGBTQ community but asexuality? The mainstream acceptance and understanding of what it actually is – the idea that sexuality is a spectrum – it's still not there.

The asexual groups – Aces NYC and Aces LA – help promote, understand and connect with other aces. They brainstorm on activism, trying to move the needle toward mainstream understanding.

These groups brought the book home because their own understanding of asexuality really comes from the Internet. One woman didn't know what she identified as and was confused about it. Then she saw a viral reblog on Tumblr floating onto a message board about an asexuality meeting. She realized, "I feel that way. That's how I approach relationships." The Internet is driving that understanding.

The parrot group: tell me about those folks.

Oh my god, the parrot group. They just meet at this man's apartment in the Bronx, drink all day and have their parrots hang out with them. It was like a bunch of parents coming together to drink while the kids are in the other room, except the kids are parrots flying around, saying "Hello". They talked about the personalities of their birds, shared videos and even brought out a pet snake that we passed around the table while we drank champagne.

How do online meetups impact people's idea of what's "normal"?

I don't know what normal is any more. I don't think it exists and I hope that when people look at the book, they can see this. I told the guy who runs the Harry Potter meetup about a scrapbooking meetup that I went to in Tennessee and he said, "And people think we're weird? Scrapbookers are way weirder than us." What people perceive as weird is an individual thing.

All the squishy acceptance aside, is it narcissistic to socialize with others based on your shared hair colour or your dog's breed? Does it make people insular, to be meeting increasingly with only like-minded people?

I don't think so. You have to find the support system that works for you. That depends on what gets you down and what's going to make you feel more comfortable. Some people like shared commonality, some jumping off point to explore and deepen the relationship. What we want in a community is very individual.

This interview has been edited and condensed.