The wildfire MWF-009 was first spotted by an Alberta Agriculture and Forestry crew on Sunday afternoon, and was logged just after 4 p.m. Its technical name signified it was the ninth wildfire of the season in the Fort McMurray area, the only one burning that day. Nothing was especially remarkable about it at first: 500 hectares burning in the trees southwest of the city. But the fire was already out of control, and wildfire officials knew they were on the edge of an exceedingly dangerous fire season. All the conditions for a catastrophic wildfire were present: Hot dry weather, high winds and low humidity, set within a dense boreal forest primed to burn. MWF-009 was also unsettling because of its proximity to the city, and it was already proving itself to be a difficult fight. When MWF-010 flared up, it was extinguished quickly, but MWF-009 persisted.

By Monday, 80 firefighters were working on the fire, with tankers and helicopters attacking it from the air. Yet by 5 p.m., the fire had more than doubled in size to 1,285 hectares. Three hours later, it had doubled again.

On the morning of Tuesday, May 3, Fort McMurray Fire Chief Darby Allen updated the media on the fire outside the northern Alberta city. On the surface, the situation seemed to be improving. From thick smoke and roaring fire on Monday night, residents woke on Tuesday to relatively clear skies, almost as if the fire burning south of town was no longer a threat.

Chief Allen warned that that was not the case: "We are in for a rough day. It will wake up, and it will come back."

Within hours, his words proved devastatingly true. In a span of minutes, the sky over Fort McMurray turned black, the wind shifted and blew harder, and the fire that had been raging through the forest jumped the river into the city. By week's end, 80,000 residents had been evacuated, many fleeing for their lives. More than 1,600 structures were confirmed to be lost, whole neighbourhoods gone in the city that was once the heart of Canada's oil sands, an economic engine that grew from a series of rough-and-tumble work camps to a thriving, multicultural city in Canada's North.

It was an unprecedented disaster, with damage estimated to be in the billions. By Friday, the fire had grown to more than 101,000 hectares, significantly larger than the city of Calgary.

In a short video released late Thursday night, Chief Allen delivered a grim message to residents. "The beast is still up," he said. "It's surrounding the city and we're here doing our very best for you."

And the fire was still burning, and growing fast.

Monday:

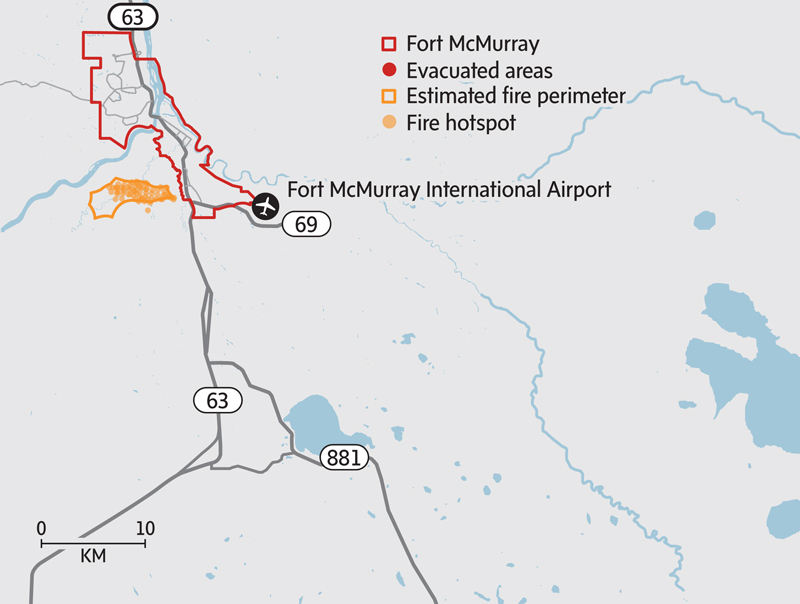

Maps by Murat Yukselir/The Globe and Mail

Maps by Murat Yukselir/The Globe and Mail

Watching the fire burn

Living within the boreal forest, residents of Fort McMurray are used to wildfire in the distance, to smoke in the air. Wildfire is a natural part of the boreal environment, and it is not uncommon for blazes to be burning in the distance during wildfire season.

"We've seen fire before," said Kwame Osei, a former Toronto Argonauts receiver who coaches football and teaches at Fort McMurray's Trinity High School.

Mr. Osei was among several residents who watched the fire burning outside the community on Sunday, but it was more out of interest than concern. An evacuation order for 500 people in the Prairie Creek suburb south of Fort McMurray was lifted on Monday, and by Tuesday morning, the air was so clear Mr. Osei went for a run. Although Chief Allen warned against complacency, it was easy to believe everything was fine. On his lunch break Tuesday, Mr. Osei grabbed a sub from Quiznos and mailed a package, and thought about getting gas, but decided to do it after school.

With smoke from wildfires several kilometres away, Sarah Naugle walks her horse Lady on the grounds of Greely Road School in the Gregoire subdivision on Monday. Aircraft dropping fire retardant are working with crews on the ground to protect homes from an uncontrolled wildfire close to the city.

Greg Halinda/THE CANADIAN PRESS

Then, around 1:30 p.m., the wind changed, and the fire that had been burning parallel to the city suddenly changed course.

From the window of his classroom, Mr. Osei watched dark clouds billowing in, spreading across the sky. Seeing what was coming, he gathered his students and together they prayed for safety, guidance and strength.

At 2 p.m., the fire was inside city limits, and houses on the edge of the community were burning. People from neighbourhoods under mandatory evacuations began rolling through town: Abasand, Beacon Hill, Waterways, and on. Long lines formed at gas stations in all directions as people hurriedly prepared to leave town, but tanks soon ran dry.

Jordan Stuffco, an Edmonton defence lawyer who grew up in Fort McMurray and has an office there, considered leaving earlier in the day, but decided against it. He and some sheriffs had watched the fire from the roof of the courthouse.

Harrowing escapes

When the wind changed and the fire roared in, Mr. Stuffco got into his car and turned onto Highway 63, joining a line of vehicles jammed on the only road heading south out of town. Mr. Stuffco watched RCMP officers direct traffic as emergency vehicles flew by, and burning embers started falling from the sky.

Large fires were raging in the trees along the road, cars were abandoned in the ditch, and sparks skittered along the highway. Thick black smoke hung low overhead as streams of cars headed slowly through the dark in both directions.

On the highway near Beacon Hill, Mr. Stuffco watched his friends' neighbourhood going up in flames. A gas station exploded as he passed. It was only then that the reality of the situation started to sink in. "Nobody is in control," he thought. "This fire is out of control. Nothing is going to stop it."

Tuesday:

Inside the city, some people were driving on sidewalks, trying desperately to make their way out of town. There were only two ways to go: South toward the fire, or north toward the wilderness and work camps.

With his gas tank on empty, Mr. Osei left his apartment on foot, but met a student whose father gave him half a tank of gas. Although emergency officials were saying to go north, Mr. Osei and his wife decided to go south, not wanting to be trapped in a northern camp if the fires continued to burn.

At the Northern Lights Regional Health Centre, doctors, nurses and staff hurriedly loaded 105 patients into buses and moved them to an oil sands site north of the city, where they could be transported to other hospitals by air. There were nine babies from the neonatal unit and their mothers, intensive care patients, and those in continuing care. A pet cat and bird from the continuing care facility were taken with the group. The last person left the hospital at 7:30 p.m., after a final check to make sure no patients had been left behind.

Social media filled with images and videos documenting harrowing escapes from the fire. In tweets and Facebook posts, people expressed their shock, mourned, begged for help. In some of the videos, people can be heard swearing or crying, other times saying only: "Oh my God."

Abandoned vehicles litter Highway 63, south of Fort McMurray as residents fled the wildfire engulfing the city on Tuesday. Fuel shortages are being reported in the evacuation area.

HO-Brian Langton/THE CANADIAN PRESS

'A nasty, dirty fire'

While 80,000 people flooded out of the city, others rushed toward the blaze. Wildrose Party leader Brian Jean and Fort McMurray-Wood Buffalo MLA Tany Yao, both residents of the city, headed north. (Mr. Jean later confirmed that his home was destroyed.)

Legions of firefighters, RCMP, and other first responders were also on their way. Among them was Slave Lake Fire Chief Jamie Coutts, who battled devastating wildfires in his own community five years earlier, in May, 2011.

"It's bad," he texted from inside the Fort McMurray blaze on Tuesday evening. "It's a firestorm. Propane popping everywhere. Sirens everywhere. Brings a flood of horrible memories."

At the time, Slave Lake was one of the most devastating disasters in Canadian history, but Fort McMurray would be far worse.

Wednesday:

By Wednesday, the fire at Fort McMurray was nothing less than a nightmare. People described it as hell, or compared it with movies, to war, to the end of the world. It had grown to more than 10,000 hectares, and was resisting all efforts to control or stop it.

"This is a nasty, dirty fire," Chief Allen said during a media briefing on Wednesday morning. "There are certainly areas within the city that have not been burned, but this fire will look for them, and it will find them, and it will want to take them."

Fire crews had worked throughout the night and made some progress putting out fires within the city, but the fire and smoke were so extreme they restricted attempts to fight it from the air, and new hot spots were flaring up outside its main perimeter. Another day of extremely hot, dry weather escalated the situation.

Video courtesy of Jordan Stuffco

Fort McMurray forestry manager Bernie Schmitte said firefighters were using "all possible tools to engage this fire," but without success. "To date, this fire has resisted all fire suppression methods."

Mr. Schmitte described the blaze as "a very complex fire with multiple fire fronts and explosive conditions.

"It's challenging all of us."

By then, about 1,600 structures were confirmed to have been lost, and the fate of many others was still in the balance. The fire around Fort McMurray was so big it was visible from space. So hot, it created its own weather system, its own wind and lightning. In addition to its technical name, the blaze would officially be called the Horse River Fire, after a river winding through the area where it started.

Its cause remains under investigation.

A Canadian Joint Operations Command aerial photo shows wildfires near neighborhoods in Fort McMurray Wednesday posted on social media.

Courtesy MCpl VanPutten/CF Operations/Handout via REUTERS

An outpouring of help

Asked whether it was possible the whole town could be destroyed, Alberta Emergency Management executive director Scott Long answered: "It is a possibility that we may lose a large portion of the town."

Premier Rachel Notley declared a provincial state of emergency on Wednesday afternoon, giving expanded powers to the province in managing the scene. Around the country, mechanisms kicked in to help the city and its residents in other ways. The Canadian Armed Forces were deployed to the scene, and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau pledged "total support" to those affected by the disaster. "It is a loss of a scale that is hard for any of us to imagine," he said on Wednesday. "As Prime Minister, I want you to know our government and all Canadians will stand by you now and when it's time to rebuild."

Mr. Trudeau also announced the federal government would match private donations made to the Red Cross, which has raised more than $30-million.

Reception sites were set up around the province to deal with the unprecedented evacuation, the flood of humans needing food, shelter and essential supplies. Many fled their homes with only the clothes they were wearing.

Other people helped in whatever way they could. Some drove north to deliver gas and supplies to those still stranded, while others offered their homes on social media or over the radio, even holding signs on the highway south of the fire zone. People bought food and bottled water to distribute, or donated diapers, personal hygiene supplies and other amenities to reception centres housing.

Companies offered free phone calls, free tire service, free storage to evacuees. Fresh off a controversial decision to stop using Canadian beef, the Earls restaurant chain offered a free sandwich and drink for anyone with a Fort McMurray address. (The beef decision was reversed mid-week.) Animal welfare groups offered help with animals that had been evacuated, and began making rescue plans for when they are allowed to enter the community. Messages of condolence and support poured in from people around the country and the world, everyone from the Queen to Alex Trebek.

The mayor of Lac-Mégantic, Que., devastated by its own disaster when a train derailed and exploded in the town in July, 2013, announced his community would make a donation to help those in Fort McMurray. "We can only feel solidarity," Jean-Guy Cloutier said.

In Calgary, Syrian refugees who have been in Canada less than six months organized their own effort to help.

"If there's a large group of people in Canada right now that understand what it's like to lose everything, it's these Syrian refugees," said Saima Jamal, co-founder of the Syrian Refugees Support Group. She said one Syrian child wanted to donate all the toys that had been donated to him.

Thursday:

'Herculean' efforts

By Thursday morning, the fire around Fort McMurray had ballooned to an alarming 85,000 hectares – the size of the city of Calgary – and was continuing to grow. People who had been evacuated to the hamlet of Anzac southeast of Fort McMurray were moved again during the night as the fire changed direction and spread toward them. In Fort McMurray, structural firefighters fended off the blaze in spots throughout the city, trying to save key infrastructure sites. Firefighters were able to keep the airport from burning and hold the fire back from downtown with efforts described by officials as "herculean."

Evacuees from the wildfires use the sleeping room at the “Bold Center” in Lac la Biche, Alberta on Thursday.

Mark Blinch/REUTERS

Additional resources continued to pour into the community to help combat the fire. By Thursday, there were more than 1,110 firefighters, 145 helicopters, about two dozen air tankers and a fleet of heavy equipment, with other fire resources arriving from Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

Plans were also being made to move the approximately 25,000 people who had either fled north or were already there when the fire spread.

Heavy smoke prevented travel on the highway on Thursday as planned, but the first convoy of 400 vehicles left on Friday morning, travelling south through the fire zone toward Edmonton. Led by RCMP and the Canadian military, the convoy evacuations were expected to last four days. The province also hoped to have another 16,000 people moved south in mass airlifts by Friday night.

Friday:

'Nothing left to give'

Although no known deaths have been directly associated with the fire, two teenagers were killed in a highway crash south of Fort McMurray on Tuesday, which in turn started a new fire along the highway. RCMP have said the cause of the crash remains under investigation. The victims have been identified as 15-year-old Emily Ryan and 19-year-old Aaron Hodgson.

"I have quite literally nothing left to give," Ms. Ryan's sister Chelsi wrote on Facebook. "I do not know what else this fire could possibly take from my families."

On Thursday, a water-tanker plane made an emergency landing after the pilot suffered a medical episode, but RCMP said the injuries were not life-threatening.

Amid the destruction and chaos, there were also reports of one birth at an oilfield housing camp on Tuesday.

Paul Spring, president and operations manager with Phoenix Heli-Flight, used his helicopters to rescue a number of people who were cut off in Draper, an area of acreages just outside the city. His EMS aircraft was used to help transfer intensive-care patients from the hospital.

"I just hope that when the smoke clears, we don't find bodies," said Mr. Spring, who lives in Fort McMurray and has been fighting fires in northern Alberta since 1980. "You have to start thinking about people who maybe were sleeping in their homes, shift workers or people who are care-bound in their homes, or the homeless people that usually live downtown along the river."

Drivers of a resupply convoy stand outside their vehicles south of Fort McMurray as a wildfire blocked the only highway to the city. Nearly 25,000 of Fort McMurray’s 90,000 or so residents fled north to isolated oil industry work camps when the city was ordered evacuated, but supplies there quickly ran low.

Tyler Hicks/The New York Times

'Not leaving without a fight'

There is currently no timeline for residents to re-enter the city, and officials have said it will not be safe for people to return for "a significant amount of time."

Officials have also repeatedly stressed that the fire around Fort McMurray remains a dynamic and changing situation, an extreme wildfire that is not yet under control, and volatile conditions persist through much of the province. On Thursday, the government announced a rare, Alberta-wide fire ban, and asked people to stay out of the forest, where even the heat from off-road vehicles can spark fires in dry conditions. On Friday, the measures were expanded to include a total ban on the use of recreational ATVs. There were 36 wildfires burning on Friday, only one of them the Horse River Fire. Five were considered to be out of control.

By Friday, the fire around Fort McMurray, grown to 101,000 hectares, was expected to be shifting toward the forested area in the north. Wildfire officials said the fire could double in size by Saturday evening.

From the safety of a friend's house in Morinville, north of Edmonton, Kwame Osei said he was confident his community will rebuild, and may even grow closer, after the disaster. He said he is thinking of those who lost their homes, and of those still inside the city trying to stop the blaze.

One of his friends, a firefighter, sent him a message from inside Fort McMurray that read: "I'm not leaving this place without a fight."

With reports from Kelly Cryderman and Allan Maki