Two years ago this week, Ray Carlberg was in seventh heaven.

The University of Toronto astronomer had just learned that then Prime Minister Stephen Harper was about to commit Canada to help build the Thirty Meter Telescope, one of the largest and most ambitious instruments ever conceived for peering into the cosmos.

As the Canadian point man for the $1.5-billion science megaproject, Dr. Carlberg had spent years marshalling support for just such a decision. He had campaigned hard to bring colleagues and bureaucrats onside, making the case that partnership in TMT, as the telescope is known, would give Canada a role in the next big wave of cosmic discoveries – from potentially finding another Earth to capturing the light of the universe's first stars.

Tight federal budgets and a disinterested government had seemed certain to doom his efforts. But within weeks of a final deadline for Canada to join the project, an 11 th-hour decision from the Prime Minister's Office cleared the way. Canada would allocate $243.5-million to the giant observatory, Mr. Harper announced on Easter Monday, 2015. The money would go toward building TMT's enormous dome and supplying part of the telescope's advanced optical system developed by astronomers at the National Research Council. Astronomers and the Canadian firms most likely to be part of TMT's construction were ecstatic.

Today, Dr. Carlberg finds himself openly questioning the arrangement he worked so hard to cement. In a surprising reversal, he now advocates that Canada take a hard look at what it's gotten into – an opinion that triggered his ejection from the TMT board late last year.

"This project is in a lot of trouble," Dr. Carlberg said in an interview with The Globe and Mail. "Part of the reason I raised the alarm is I wanted to give the community time to think about this."

Many of his colleagues disagree. They remain emphatic that the best future for Canadian astronomy lies with TMT.

At its roots, the unforeseen controversy is about one thing: Location, location, location.

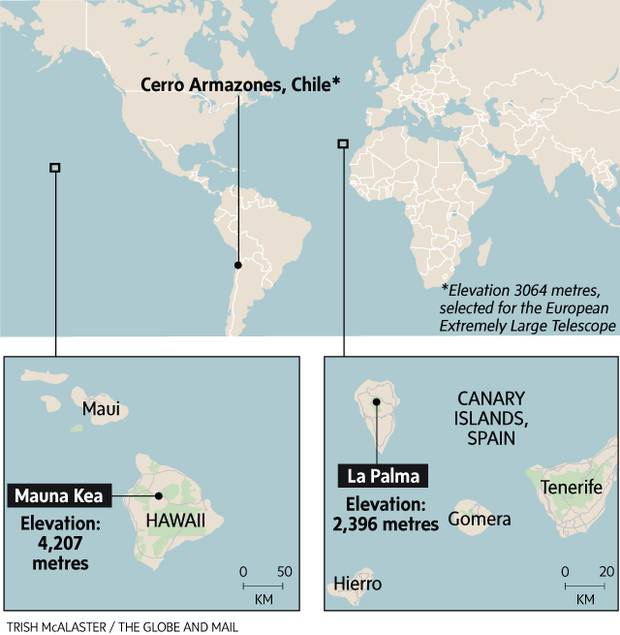

When Canada officially signed on to TMT, the telescope was slated for construction atop Mauna Kea. The Hawaiian peak rises 4.2 kilometres above sea level and is already home to several major observatories, including the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope. It is universally acknowledged to be the best site for astronomy in the northern hemisphere.

The Thirty Meter Telescope plan has prompted protests because native Hawaiians say the mountain is sacred and should be off limits to further development.

Todd Mason/Thirty Meter Telescope Project

But

TMT's plans at Mauna Kea have been stalled by protesters who regard the mountain as sacred to native Hawaiians and who seek to prohibit further development of scientific facilities there. For many, the issue has become part of a complex and politically charged discussion over Hawaiian identity.

On March 4, a Hawaiian court wrapped up nearly five months of hearings in a contested case to determine whether the project can proceed as planned. It will likely be months more before a decision is reached, after which additional proceedings and appeals could follow.

Meanwhile, financial pressures are mounting on TMT's California-based consortium, to the tune of millions of dollars a month, while the planned observatory is sidelined. The leaders of TMT have stated that they must determine by October where the telescope is going to be built so that the decade-long construction project can begin without incurring further costs due to delays.

Last fall, the group selected a site at La Palma, one of the Canary Islands, as a backup in case the situation in Hawaii cannot be resolved in time. La Palma, which belongs to Spain, hosts other observatories and would welcome a major international research facility. On Wednesday, TMT executive director Ed Stone announced the group had signed an agreement with the institute that oversees the La Palma site, which ensures that there will be a place to build TMT "should Mauna Kea not be feasible."

This has dismayed Dr. Carlberg and some other long-time Canadian advocates of the project – for the simple reason that the peak of La Palma is 1,800 metres lower than Mauna Kea. The difference amounts to a significantly thicker layer of air and turbulence between the telescope and some of the faintest and most distant objects in the universe. Additional worries have been raised about dust blowing in from the Sahara. The air over La Palma also holds more moisture, which blocks light in the mid-infrared part of the spectrum, where certain astrophysical targets, including the atmospheres of Earth-like planets, are best observed.

These are serious downsides, Dr. Carlberg says, particularly if it means that TMT is less likely to attract the additional partners it needs in order to be fully funded. If TMT goes to La Palma, he says, Canada should consider jumping ship. But while everyone agrees that Mauna Kea is the better place for TMT, many do not share Dr. Carlberg's dismal assessment of La Palma.

"It turns out to be a really excellent secondary site in many respects," said Doug Welch, a McMaster University astronomer who replaced Dr. Carlberg on the TMT board.

According to Dr. Welch, the technical stats on La Palma's viewing conditions are far better than its detractors suggest. On average, dust levels compare favourably with Mauna Kea, and the stability of the air flowing above the site makes it well suited to the TMT's adaptive optics – a technology that astronomers use to cancel out the effects of air turbulence on coming starlight.

Even the mid-infrared work can be achieved, Dr. Welch said, with protocols in place to prioritize those kinds of observations when conditions are just right.

U.S. astronomer Charles Telesco of the University of Florida has been observing at precisely those wavelengths for many years, both at La Palma and Mauna Kea. While the Hawaiian site is generally preferred, he said, "If TMT cannot be sited on Mauna Kea, then, in my opinion, La Palma is a reasonable alternative."

But the debate among Canadian astronomers is not just about how La Palma compares with Mauna Kea. More to the point is how it will stack up against its chief competitor, the European Extremely Large Telescope (EELT), now being built on a high, dry mountain top in Chile.

From the outset, TMT was always going to be a bit smaller than the European scope. As its name suggests, its vast primary mirror will measure thirty metres across, compared to the EELT's even larger 39.3-metre aperture. But TMT's participants have always maintained that theirs will have superior technical performance, making it equal or superior to the European scope.

Dr. Carlberg said this equation no longer holds at La Palma. If TMT ends up going to the Canary Islands, then the bottom line is that Europe will have "a bigger telescope on a higher, better mountain," leaving Canada as part of an astronomical also-ran.

Instead of settling for La Palma, Dr. Carlberg says Canadian astronomers should be ready to make a pitch to join the European telescope. Canadian astronomers discussed the European option years ago but ultimately chose TMT, in part because joining with Europe's astronomy enterprise would require the Canadian government to pass a treaty in Parliament, an even higher political hurdle than it took to get TMT approved. And it's not clear at this stage whether Europe needs Canada as part of its telescope – at least not the way TMT needs Canada, including the Canadian dome and optical systems.

A laser on the Thirty Meter Telescope will help the observatory take space-quality images.

Roberto Abraham, president of the Canadian Astronomical Society, whose U of T office happens to be just down the hall from Dr. Carlberg's, dismisses the European option because he says it would leave Canada with relatively little influence in a much larger research collective. And, he predicts, even at La Palma, TMT will outperform Europe's giant telescope.

"My plan is to crush them like bugs," Dr. Abraham said.

Others warn that Canadian astronomers might risk losing everything if they push the federal government to switch tracks and re-allocate the money it set aside for TMT. That money could just as easily be spent in another field of science, they say, or moved away from science entirely.

For now, the National Research Council, which oversees Canada's participation in the project, says it backs TMT and its selection of La Palma as an alternate site. Charles Drouin, a spokesman, also said that the NRC would continue to consult with Canadian astronomers "to ensure our participation benefits Canadian researchers, students and industry."

"We are aware that there are various opinions out there," Mr. Drouin added.

The debate has generational overtones. Those who say Canada is better off sticking with TMT, even if it is forced to give up on Hawaii, tend to be mid-career astronomers and younger. Those with the strongest doubts are among the senior scientists who were the earliest champions of TMT in Canada.

For example, Luc Simard, who is currently overseeing the development of Canada's optical contributions to TMT for the NRC, says he is confident the telescope will perform well at La Palma. In contrast, Rene Racine, a professor emeritus at the University of Montreal who is widely respected for optimizing the astronomical returns of the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope, said that building TMT at La Palma would be a "great disappointment."

Dr. Racine said Canadian astronomy would lose too much if it follows TMT to La Palma, but concedes that his opinion "is not the majority view in the community."

A 2004 artist’s concept of the Thirty Meter Telescope.

Todd Mason/Thirty Meter Telescope Project

In January, University of Waterloo astrophysicist Michael Balogh was tasked with chairing a committee to address questions about the TMT project and the La Palma site on behalf of professional astronomers across Canada. The committee is now holding web seminars to inform the community on various technical details.

"If we have to go to the alternate site then we need to understand what the impact will be on the science performance of TMT," Dr. Balogh said.

In the coming months, the committee will issue a report that will be taken on board as a recommendation from the community to help steer Canada's long-term goals in astronomy.

Meanwhile, Canada's rank-and-file astronomers who are hoping to some day make discoveries using TMT are wondering how it will all play out. Many expressed mixed feelings.

Kim Venn, an astronomer at the University of Victoria, said that, for her part, TMT at La Palma would perform well for the kind of research she does on metal-poor stars. But she also wonders what other big and possibly unforeseen discoveries might be precluded if the giant telescope ends up there.

Asked what outcome she is wishing for, Dr. Venn paused and said, "I wish for TMT on Mauna Kea – period."