From his ground floor office window at Boyne Public School, in Milton, Ont., principal Peter Marshall can see the line of houses moving closer.

His school already has more students than space. Sixteen portables serve as classrooms; there's room for two more on the field. Mr. Marshall knows he will fill them. Just outside the school building, yellow machinery rumbles over old farmland, clearing the path for rows of tightly packed new homes for even more young families.

"They're coming towards us," Mr. Marshall says, glancing out the window. "The rapid growth here is something that I've never seen."

In many ways, Mr. Marshall is in an enviable position. School boards in many parts of the country face declining student enrolment. Schools in Milton, on the western edge of the Greater Toronto Area, can barely keep pace with the tremendous growth. One school board official jokes that the school parking lots are as bad as Toronto highways at rush hour.

But the rapid expansion that makes Milton the fastest growing community in Canada has also brought serious challenges. There are divisions between old (often white) Miltonians and the multicultural newcomers. Roads are congested and infrastructure hasn't kept up. Schools, once small and quaint, have had boundaries routinely redrawn to keep up with the wave of new families; students have been moved multiple times; and clusters of portables have become a normal part of the landscape in Milton neighbourhoods.

"We're always in a catch-up mode," says Dom Renzella, general manager of planning for the Halton District School Board. "You have the students there, and it's not like we can plop a school in in a couple of months. It's takes us a fair amount of time to go through the planning process."

The town has seen student enrolment climb 160 per cent at the elementary level over the past decade, and another 50 per cent in high schools. The student population at one school has more than doubled in the past decade, and the kindergarteners – all 200 of them – are housed in a newly built "kindie wing." They are forced to stagger recess to avoid having a mass of four- and five-year-olds all trying to put on snowpants at once before flooding outside to their playgrounds, nicknamed kindie-pens.

For at least the next decade, Mr. Renzella knows that the pressure on schools is not about to ease.

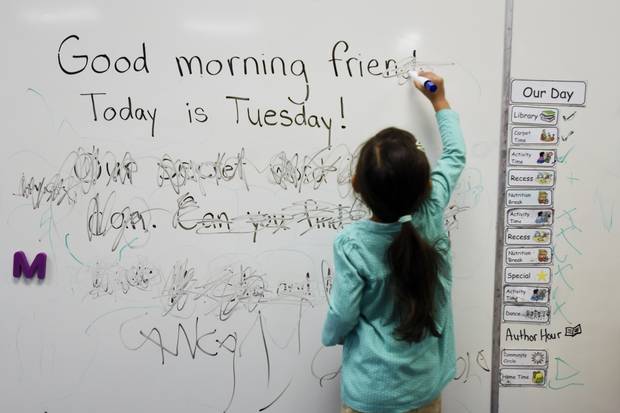

Kindergartners gather at Bruce Trail Public School in Milton, Ont.

Bruce Trail has close to a thousand students in a community that’s created a need for larger schools.

Elementary enrolment in Milton has risen 160 per cent over the past decade.

The town received funding for a new elementary school to open in September, 2018, but some fear it won’t be enough to keep up.

Milton Mayor Gordon Krantz could see the growth coming to his little mill town.

"Things move westwardly," he says. Mississauga was getting full and many former residents and newcomers to the country, mainly South Asians, were looking for reasonably priced homes that were still not too far outside Toronto. Milton was that "piece of paradise," "a nice, small community," with an abundance of undeveloped land, he says, with a smile.

The silver-haired Mr. Krantz has led the town for 36 years, making him the longest-serving mayor in a large Canadian municipality, recently surpassing former Mississauga mayor Hazel McCallion. A bobblehead of Ms. McCallion stands on a shelf behind his office chair. She's always looking over his shoulder, he quips.

Mr. Krantz, 79, says he decided to welcome the growth, rather than wrestle with it. The so-called big pipe project in the early 2000s drew water to the town from Lake Ontario. Almost immediately, developers built new subdivisions.

Last year alone, there were about 1,500 building permits issued, the majority of which were for new homes. Homes are still relatively affordable – the average sale price is around $683,444 – and newcomers are attracted to the picket-fence quality of life. Large corporations, including Lowe's Canada, have built stores and warehouses here. GO Train commuter service to and from Milton has increased, and more trains are expected over the next five years.

In 2001, Milton barely had more than 30,000 residents. Today, it is closer to 130,000. And by 2030, Mr. Krantz estimates it will have reached 250,000.

There are still signs of small-town life. When a Globe and Mail reporter and photographer were visiting on a recent weekday, Mr. Krantz had gone home for lunch. He lives just across the street from the town hall. He prints his home number on his business card. The back of his business card features a map showing major North American centres such as New York, Washington, Toronto, Montreal, Ottawa … and Milton.

He admits that despite expecting the population boom, Milton wasn't fully prepared for it. At one point, he says, the hospital shut down its maternity ward because there weren't any babies being born in Milton. It has since reopened. The hospital is only now under construction to expand the number of beds.

Still, he says, "it's gone reasonably well."

Some long-time Miltonians lament what has been lost. They are concerned about the traffic, and the new cultures moving in. Schools in Milton, for example, have seen the number of English-language learners increase, more so than in other areas of the school board, which include Burlington and Oakville.

Ries Boers lives next door to the mayor. He has lived in Milton most of his life, and raised his own children here. He understands change is inevitable, but at the same time he misses walking to the market on a Saturday and knowing everyone. Some old Miltonians, he says, have chosen to leave the town as it began to grow.

"Old Milton was a community. If you add enough colour to clear water, eventually it's going to change the culture. And that's what happening," he says. "We're a little overwhelmed. That's the way some people perceive it."

A wall by the entrance to Boyne Public School is covered in greetings written in many different languages. Milton’s growth is changing the ethnic and racial diversity of the town.

Adene Taylor remembers the racism – sometimes subtle, sometimes overt – she experienced growing up in Milton. She's black. She's lived here for 40 years.

A teacher at a nearby school board, Ms. Taylor says she appreciates how Milton has changed, not only for her, but for her two school-age children.

"There may be some old Miltonians that would prefer if the demographics hadn't changed. I'm certainly sure [that attitude] exists," she says.

Her daughters attend Martin Street Public School in the old part of Milton. But at the moment, all 200 Martin Street children are at Boyne, Mr. Marshall's school, as their school undergoes renovations that will hold more than 700 children. Many of those new students are expected to come from the new, more diverse Milton.

"As a person of colour who grew up in old Milton, I'm really happy for the diversity," Ms. Taylor says. "I'm really happy that my kids will be exposed to a broader range of people, cultures, religion."

She adds: "It's important to me. It's not something I had growing up."

Other parents echo her sentiments about the diversity in Milton, but they also worry that they are living in a town in transition. Some families don't stay in their home for very long, because a new subdivision around the corner has bigger houses. New students are constantly joining schools, making it difficult to have a sense of community.

Lisa Chemerys, a mother of three, has lived in Milton for five years. Her family bought a three-bedroom townhouse in a new subdivision after renting in nearby Oakville. She's looking to leave Milton.

"People are just constantly moving. I don't feel a high sense of community in my neighbourhood in Milton," she says.

There's another issue, too.

School boards alter school boundaries to address crowding issues at schools or if a new school is built. Ms. Chemerys's eldest daughter, seven-year-old Kira, has moved schools three times in three years because of boundary changes. Ms. Chemerys is not looking forward to the possibility of more moves.

"You don't feel connected or attached to a school. You kind of feel like you're being thrown around," she says. "Right now, I'm pretty confident that we're so close to the school, we shouldn't get switched. But with this whole neighbourhood being built, I mean really, anything can happen."

Zeeshan Hamid, a Milton town councillor and a parent, understands the concerns.

His nine-year-old son is in a portable, not the most ideal learning environment because students feel isolated from the school building, Mr. Hamid says. The school year for his son started in the library, because there were no classrooms available and the portable hadn't arrived.

He acknowledges that the school board is using portables so that it won't overbuild, especially when the population in Milton stabilizes. A better solution, he says, would be to design schools for the student population they have now, and then find different uses for the extra spaces a decade or two down the road.

School board officials say they design schools to accommodate future student enrolment so they are not faced with half-empty buildings as the community population stabilizes.

"Any school board planner will tell you – although parents won't agree with it – portables are good planning," says Mr. Renzella, the general manager of planning for the Halton board. "We don't want to overbuild because … it's happened in other jurisdictions, including our board, where we've built to meet the capacity and now those schools are half empty and trying to go through a school closure process."

Officials say they attempt to minimize the disruption to the lives of students and their parents. But there's only a limited amount of money the education ministry provides for new projects.

The Ontario Ministry of Education does not have regional funding priorities. Instead, it funds projects based on assessments, and those with accommodation pressures receive highest priority. "We are aware of the growth projections of Halton region, and will continue to invest in school capital in growing areas of the province," says Ministry spokeswoman, Heather Irwin.

Milton has received funding for a new elementary school to open in September, 2018, and a high school that is expected to open its doors in the fall of 2019.

It won't be enough to ease the growing pressures, Mr. Hamid says.

"We're a well-off-enough province where kids should at least be comfortable in a school," he says.

Students sit outside Boyne Public School while waiting for their buses to arrive. One school board official jokes that the school parking lots in Milton’s are as bad as Toronto highways at rush hour.

At dismissal time at Boyne Public School, in a crowded gymnasium, new and old Milton sit alongside each other.

The students have poured into the gymnasium to wait from their school buses. Mr. Marshall is the on the microphone calling bus numbers.

Boyne students, mostly brown, sit in rows toward the front of the gym. Martin Street students, temporarily housed here and mostly white, sit at the back. Some mingle with each other. But mostly they stick to their bus lines.

Within a few minutes, the gym is cleared out. "Come, listen," says Mr. Marshall. It's quiet. He stops and smiles.

It won't be that way for long.

Follow Caroline Alphonso on Twitter: @calphonso

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL

In Toronto, this eight-year-old Syrian refugee is learning English in a new land