The last two decades have seen a host of advances in arthritis treatment, including the advent of biologics - drugs that target and modify immune response, but doctors are still working on potential future treatments.

The general aim of treatment for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis is pain management, said Professor Jason McDougall, a professor of pharmacology and anesthesia at Dalhousie University in Halifax."It's the number one complaint that arthritis patients take to their doctor.”

Biologics, for example, have revolutionized rheumatoid arthritis treatment, but McDougall explained that they're only effective in two-thirds of patients, and their efficacy tends to diminish over time. Current research is focusing on tweaking available biologics so they're more effective.

"Now we understand different biochemical pathways involved in arthritis, so we can also better understand the downstream events associated with them," explained McDougall, who's also chair of the Arthritis Society's Scientific Advisory Committee. The next generation of biologics will selectively target these pathways, which will potentially translate into greater efficacy and fewer side effects.

Meanwhile, science is exploring other ways to improve arthritis management. Given that there are over 100 forms of the disease, McDougall insisted that there won't be a single solution for all of the different types and stages.

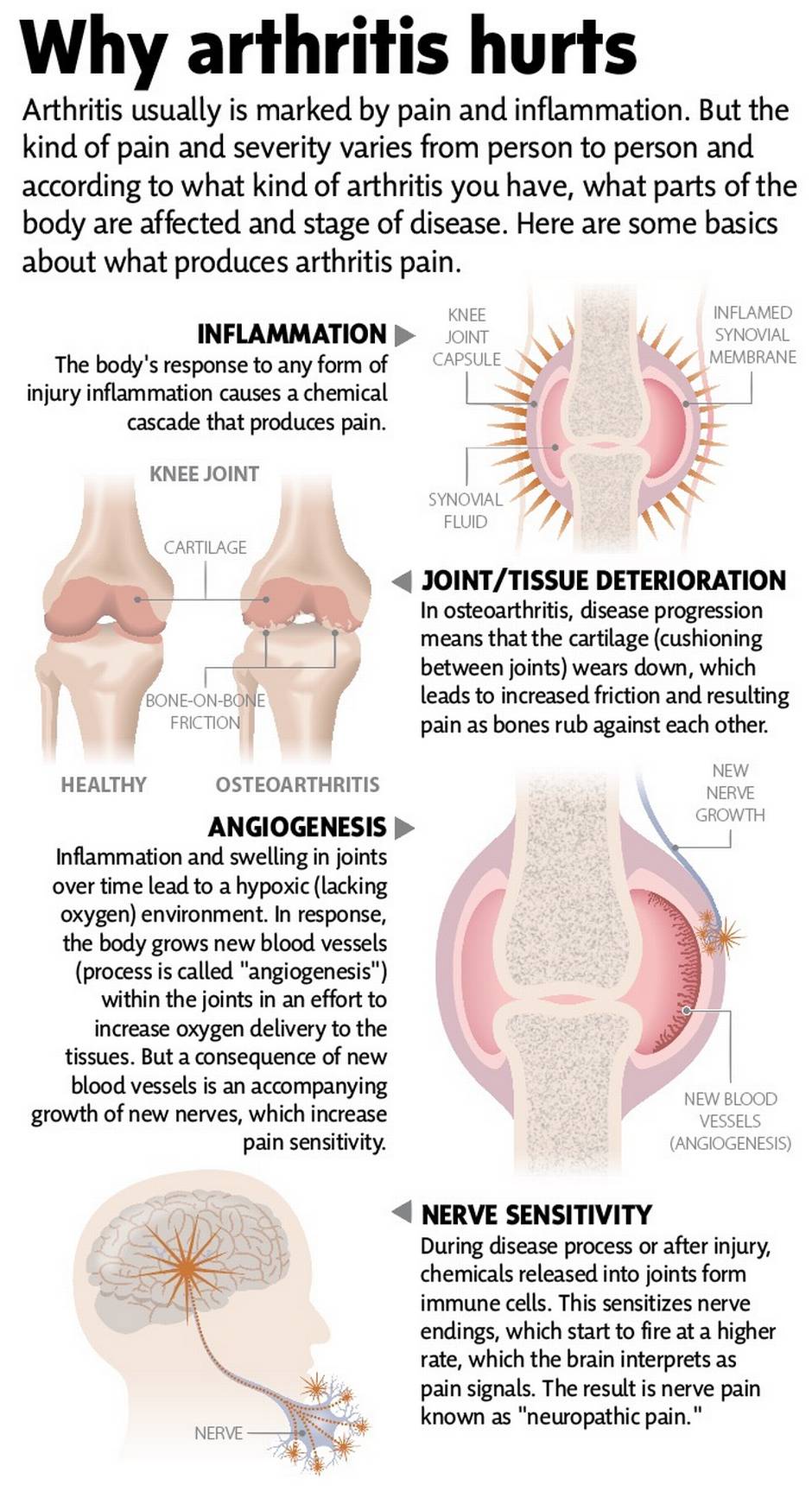

Some researchers are investigating nerve growth factor (NGF), an inflammatory culprit that's elevated in the synovial fluid of joints affected by osteoarthritis and contributes to pain. Findings on NGF-blocking molecules to date had shown significant pain reduction in OA patients; however, clinical trials were halted in 2011 when a few patients showed accelerated disease progression. Clinical trials have reopened now, which McDougall predicted will yield exciting results.

McDougall is investigating tapping into the body's cannabinoid receptors to treat osteoarthritis pain."We know now that the body produces endocannabinoids, which have anti-inflammatory properties and fight associated pain as well," he said. Two therapeutic options might come out of this knowledge. A potential big breakthrough, McDougall said, could be finding a way to target cannabinoids within the joints and blocking the enzymes that break these natural pain relievers. So far, preclinical studies in mice with arthritic knees have shown that it's very effective for osteoarthritis.

Another possibility, which McDougall is working on, is developing a spray or cream for localized pain. McDougall estimates that his work will yield a novel therapy for patients within five to 10 years.

Other potential approaches include antiangiogenic therapies, which reduce the growth of blood vessels in joints. McDougall explained,"Swollen joints become hypoxic, so the body's response to lack of oxygen is to grow new blood vessels. Unfortunately, nerves come along with them, which means heightened pain response." Blocking the unwanted blood vessel growth could help to reduce pain due to nerve sensitivity.

Gene-targeted therapy is another area being explored specifically for ligament healing. Researchers are interested in administering genes to patients that activate healing proteins. Findings from the University of Manchester suggested that a gene mutation in some individuals may determine their risk of developing RA, disease severity and response to biologic treatment. Researchers hope such insights about genes may hold the key to designing more individualized and targeted treatment for RA patients.

One of the most exciting research areas for arthritis, and many other diseases, is stem cells. A blank slate, these programmable cells in the body have the ability to regenerate and differentiate into different, organ- and tissue-specific types of cells. In the case of OA, through tissue engineering, stem cells offer the possibility of growing and replacing damaged cartilage in knees. Also, a number of researchers around the globe are investigating the potential for reversing or repairing the overzealous immune response that underlies RA.

At Toronto General Hospital, researchers are conducting the first osteoarthritis stem cell study in North America, which involves 12 patients, ages 40 to 65, with moderate to severe osteoarthritis of the knee. Extracting stem cells from patients' own mesenchymal (bone marrow) cells (MSCs), the researchers grow them for four weeks in vitro, then inject them into patients' knees.

A handful of clinical trials around the world on MSCs for arthritis have shown stem cell therapy to be safe and effective for pain relief."For OA, there's already study evidence to say that, if you inject or implant stem cells into animals, cartilage volume increases, pain and inflammation decrease, and there seems to be some regeneration as well" explained says Dr. Jas Chahal, an orthopedic surgeon at the hospital and one of the study's lead investigators.

The Toronto team's aim is to decipher how stem cells relieve pain and how they interact with the immune system, so they can optimize their therapeutic punch. If the study findings pan out, orthopedic surgeons' schedules may open up a bit, since they would conceivably be performing fewer knee replacements."But the idea would be to initiate stem cell therapy before disease progresses to late stage—you're not going to replace a whole lost knee," said Chahal.

Besides newer and better drugs, arthritis patients eagerly welcome any non-pharmacological therapies,"but this is a research area that definitely requires more rigorous investigation," said McDougall.

TYLENOL® Arthritis Pain is indicated for the fast, effective relief of mild to moderate osteoarthritis pain.

This information does not constitute a diagnosis of any medical condition or medical advice, including advice about the treatment of any medical condition. Do not substitute this information for medical advice. Always consult your physician or health care provider if you have medical or health questions or concerns.

This content was produced by The Globe and Mail's advertising department, in consultation with Tylenol. The Globe's editorial department was not involved in its creation.