Show business builds a tolerance for rejection – people say no, a lot.

During a couple of decades toiling in the music industry, variously as an agent, producer, road manager, stagehand, ticket-seller and general dogsbody, Normand Piché acquired the appropriate baggage – work ethic, thick skin, general shamelessness in chasing people for money – required for his new life.

If all goes according to schedule, he will soon be able to call himself a professional adventurer.

Piché isn’t, and has never been, a pro athlete, even if he could pass for one these days.

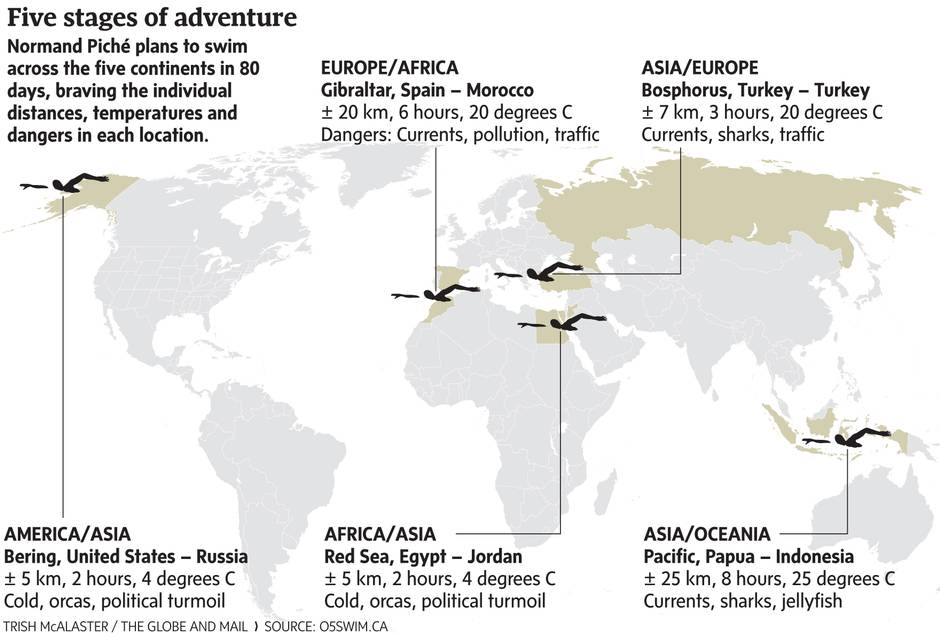

But the 44-year-old Montreal native is in the advanced stages of a plan to swim five bodies of water – the Strait of Gibraltar, the Bosphorus Strait, the Red Sea, a stretch of the South Pacific, the Bering Strait – that symbolically link Europe, Africa, Asia, Oceania and North America.

It has been done only a handful of times, and never by a North American.

The total length of the expedition – a little less than 100 kilometres in the water – tends to underestimate the magnitude of the challenge. There are sharks, glacial currents, major shipping lanes and warring militias to contend with (to say nothing of logistical obstacles and environmental pollution).

The 25-kilometre coastal swim from Papua New Guinea to Indonesia raises a particularly unpleasant possibility: encountering a nasty variety of jellyfish that proliferates in the area. “They compare it to getting stung by a scorpion. … Paralysis begins in the extremities and steadily moves toward the heart,” he said recently. “So I’m going to have to hire an emergency room doctor to be in the boat alongside.”

Managing fear is part and parcel of extreme ventures, and Piché says that, beyond the marine predators and other perils, the one thing that keeps him awake at night is the prospect of five-degree waters in the Bering Strait. “I hate the cold. I mean, really, really hate it,” he said, later adding: “But you have to find a way to do it. There are lots of examples for me to follow.”

Several are just a phone call away.

Quebec is currently witnessing a boomlet of sorts in the adventuring life.

There have been at least three or four high-profile cross-Canada canoeing odysseys in the past five years, including a group that paddled from Montreal to Inuvik, retracing the coureurs des bois routes.

Three years ago, Mylène Paquette of Montreal overcame her mortal fear of water and became the first North American woman to row across the North Atlantic by herself (the crossing was not without incident; it took five years to plan and four months to execute).

In 2015, Frédéric Dion of Trois-Rivières became the first solo trekker to reach the centre of Antarctica – he did this by kite skiing.

There are others. “It certainly feels like a bit of a movement. Or maybe Quebeckers just like to travel to strange places,” Dion laughed.

So why the sudden interest?

Dion theorizes that some of it may be linked to the broader emergence of extreme sports in recent decades.

Psychological research also has a fair amount to say about thrill-seeking behaviour. There may be a biochemical component as well: Some studies have suggested that low levels of an enzyme involved in regulating neurotransmitters may be involved.

Speaking of his own case, Dion offers a simpler answer. “I’m basically a Scout who never grew up,” he said. “I don’t believe I’m alone in this.”

Whatever the reason, it is a burgeoning industry – and it is definitely a business, complete with a well-established public speaking circuit.

Dion’s most recent contribution to it in his home province is to have co-sponsored a contest with an outdoor equipment maker to provide $10,000 for a first-time expedition.

The inaugural winner: Normand Piché.

“There were 81 proposals, and we were surprised by the quantity, yes, but mostly by the quality. There are dozens that could have won,” Dion said in an interview. “Normand’s did partly because it is so well organized. He’s done a better planning job than a lot of professionals.”

Ah yes, the planning.

Piché estimates the physical training component takes up about 35 per cent of his time, the rest is spent hustling for sponsorships and donations, organizing logistics – how does one clear Jordanian customs from the water, anyway? – and, of course, getting the word out via social media.

There is already a sponsorship in place from a large swimsuit maker, a crowdfunding effort is under way to raise $30,000, and Piché has secured volunteer help from a high-performance swimming coach, various athletic therapists, a public-relations specialist and a project-management expert.

“To get a yes, maybe there have been 99 no’s,” he said. “The music industry was great training.”

Speaking of training, Piché is stepping up his swimming regimen to 55 kilometres a week. It doesn’t give him a lot of time to spend with his teenaged daughter, but mostly the challenge is overcoming the dullness of it all. “When you’re doing eight or nine kilometres, it’s a lot of flip turns and that blue line at the bottom starts to get pretty boring. I think I know every centimetre of that pool,” he said.

He has been swimming six days a week, usually for three or four hours, at the Olympic Stadium aquatic centre; he occasionally finds himself in the pool at the same time as multiple Paralympic medalist Benoît Huot (“I wish I could swim as well as he does,” Piché said).

When weather permits, he hits the open water – the St. Lawrence River and various other lakes standing in for the swift-moving currents and chilly conditions he will face in the summer.

Piché is a direct type. The question he likes to ask people is this: What’s your dream?

He discovered his somewhat by accident in Sochi, Russia, standing in the crowd at a medal ceremony on the third day of the Winter Olympics (several Canadians accepted medals that evening).

“The first time I saw an athlete step on to the podium, the magic in their eyes, the energy of the crowd … I was completely flabbergasted by the moment. It’s when it registered what it means to reach your full potential, what it’s like in the instant where you live your greatest dream,” he said. “What it creates in other people, too. There’s laughter, there are tears, there’s pride … this is something I wanted to feel in my life.”

Piché had gone to Sochi to research a book on athletes making their dreams a reality – his partner at the time was Eric Radford, the silver-medal-winning figure skater – and simply got caught up in the theme.

He has been an avid recreational swimmer since the age of 7 – he also competed in junior meets until his teen years – so it figured the answer would feature plenty of water. “It’s been a constant throughout my life,” he said.

A few days later, in a meditative frame of mind, he sat on the patio of the house where he was staying in Sochi and jotted down a few thoughts about how he could go about it. His mind turned to swimming. “That’s when it hit me: Why not? I’m too old for the Olympics and not good enough anyway, but why don’t I define my own Olympics?” he said.

Not long after returning from Russia, he began researching unusual athletic achievements by otherwise ordinary people and came across the inspirational tale of Philippe Croizon, a quadruple-amputee from France who swam across the English Channel in 2010 and did the intercontinental divide challenge two years later.

After reaching out to Croizon’s agent to arrange a meeting, Piché read the former’s memoir and rush-ordered a DVD of the expedition (“at enormous expense,” he chuckled).

“It sat there on my kitchen counter, I could feel that when I picked it up and watched it that would be it for me,” he said. “It stayed there for a week or 10 days, when I finally put it in my computer I only watched about 10 minutes of it, then I hit pause – that was it, let’s go.”

Thinking back on the past two years, Piché said the biggest initial hurdle was to define exactly what it is he wanted to do. “I have ambitions, there are things I want, there are trips I’d like to go on, but what’s my dream? What am I really all about?” he said.

It’s a reflection he encourages everyone he meets to undertake.

He recalled a conversation on his last day in Sochi with figure skater Patrick Chan – he interviewed him for his book – where the Olympic silver medalist talked to him about selfishness.

It is, Piché said, an essential condition to wish fulfilment. “That’s not necessarily a bad thing. … Fundamentally, you have to want to do something for yourself first, that’s where dedication and motivation starts in sports,” he said.

From there, he continued, values begin to dictate the process.

“Linking Spain to Africa, well that’s a symbolic union. And that’s the message I’m hoping to spread, solidarity and togetherness. … It’s something that sounds corny and I had difficulty listening to myself say these things at first. But that’s it,” he said. “At some point, you just decide to own it, no matter how ridiculous it may sound to people.”

The cynical view is that it does indeed sound preposterous.

There is undoubtedly something New Age-y about what Piché is setting out to do – he has sometimes referred to himself online as an “explorer of human potential” – and he has his critics. After a recent television appearance, he got a note from someone via social media that said, essentially, big deal, what’s the point?

“When I got that, I was like, ‘Yes!’” he said. “People have differing opinions. … I’m very sincere about this, but I don’t expect to please everyone. I wrote back to him, and I think he at least understands what I’m trying to accomplish.”

Another critique is that adventuring has become about capitalism.

On this front, Piché pleads guilty but offers mitigating circumstances. “We’ve done a market study on revenue potential for three years, there’s a business model, if we’re able to secure major sponsors – great. If not, there will be other ways to finance it,” he said.

That said, the planning to this point has come at considerable personal financial cost.

When he announced to his family that he would be dropping everything in January of 2015 – by then he had already started training, “I basically kept the project secret for a year” – he cashed in all his savings, paid off his credit cards and began assembling the team he figured he would need to pull it off.

When the money ran out, the first sponsorships arrived. “One of the greatest challenges in this type of enterprise is to convince yourself to really believe it’s possible,” he said. “It definitely helps when you can find help just when things look like they’re going to fall apart.”

While he eventually hopes to make his living from expeditions, Piché said he isn’t particularly enthused by the prospect of pumping up corporate audiences at dinner speeches; he has pledged to give 80 free conferences to schools, youth centres and other charity groups.

Do-goodism will also be a main feature of the swim itself; the safety buoy he will trail behind him in the open water will be filled with short messages and letters – about hopes, dreams – that he is soliciting (along with a donation) through his website.

Once his expedition concluded, he will swim across Switzerland’s Lac Léman (Lake Geneva) and bring the messages to the United Nations.

Piché plans to do his metaphorical swim around the world this summer in, naturally, 80 days. Marcos Diaz of the Dominican Republic, who is credited with being the first person to accomplish the feat, did it in four rather than five legs, as did Croizon; Moroccan swimmer Hassan Baraka used essentially the same route Piché is planning, which includes the Bosphorus, but spread it over two summers.

“I may not set any records, it may not go exactly as I hoped,” he said. “But I am going to do it.”

And when he’s done, Piché already knows what comes next. A second project is already in the works. Yes, it’s a secret.