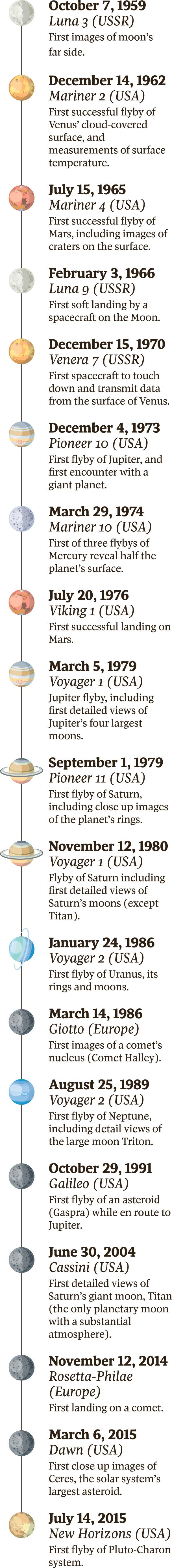

It was no tall ship – just a metal cylinder about the size of an oil drum – but on October 7, 1959, a Soviet space probe named Luna 3 ushered in history’s second age of discovery.

Launched three days earlier, Luna 3 looped around the Moon’s far side to reveal part of the surface humans had never been able to see before. Telescopes couldn’t do it; it required spaceflight.

In the era before digital cameras, Luna 3’s photos had to be shot on film, automatically developed on board, scanned and radioed back to Earth using using a Rube Goldberg-type contraption. The image quality was poor – like looking through gauze – but it was brand new territory to explore.

Over the next several decades, robot avatars with names like Mariner, Voyager and Cassini would do much more, delivering entire worlds for scientists to map and the rest of us to marvel at.

This remarkable phase of exploration has given us canyons on Mars, volcanoes on Venus and lakes of liquid methane lapping up on the frozen shores of Saturn’s giant moon, Titan. But after 56 years, humanity’s reconnaissance of the solar system has reached a turning point.

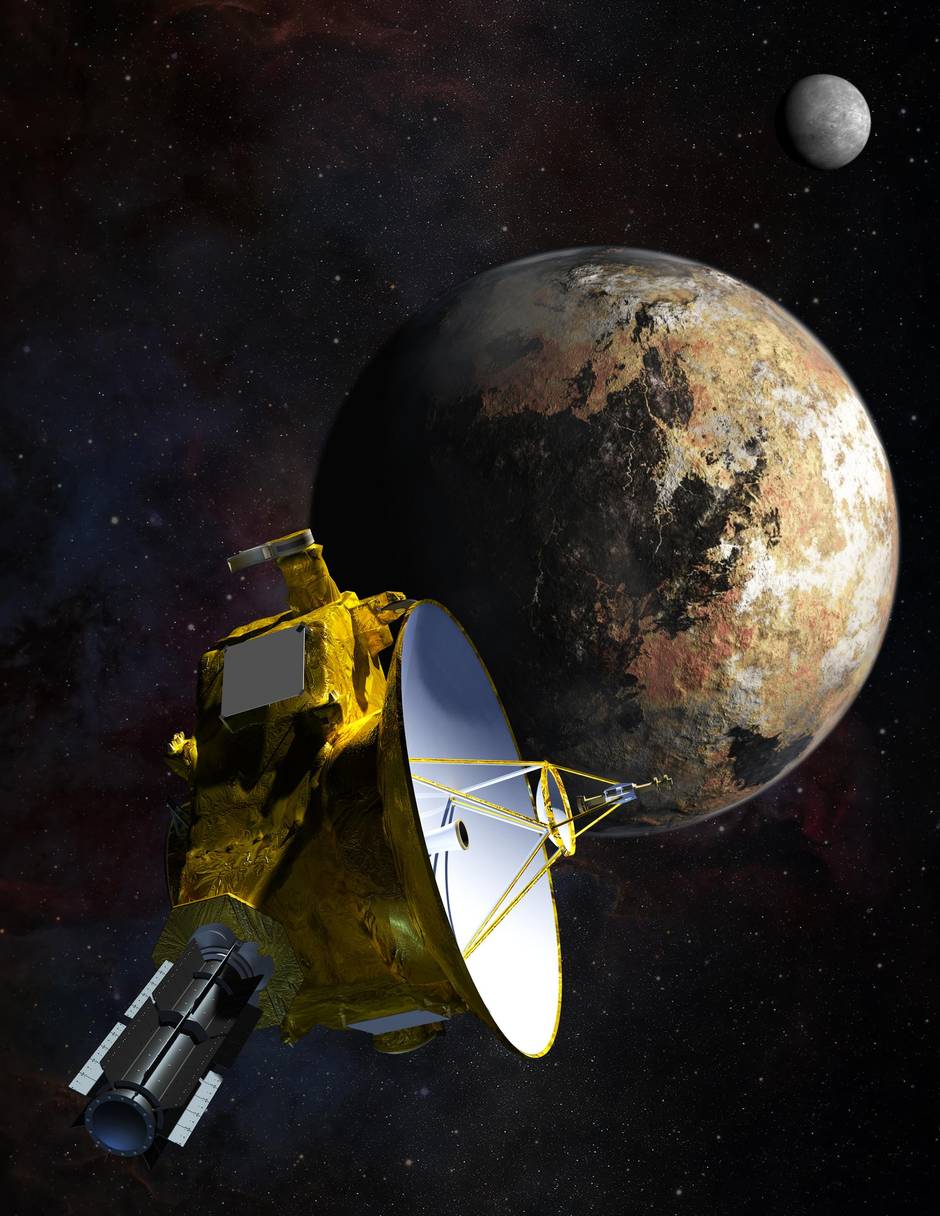

On July 14, NASA’s New Horizons probe will sail past Pluto, the most distant object ever visited by a spacecraft, and the one that completes our initial look at what’s out there – at least until we head for the stars, centuries from now.

As Alan Stern, the mission’s principal investigator puts it, “we’ve made it to the farthest place.”

Whirlwind tour

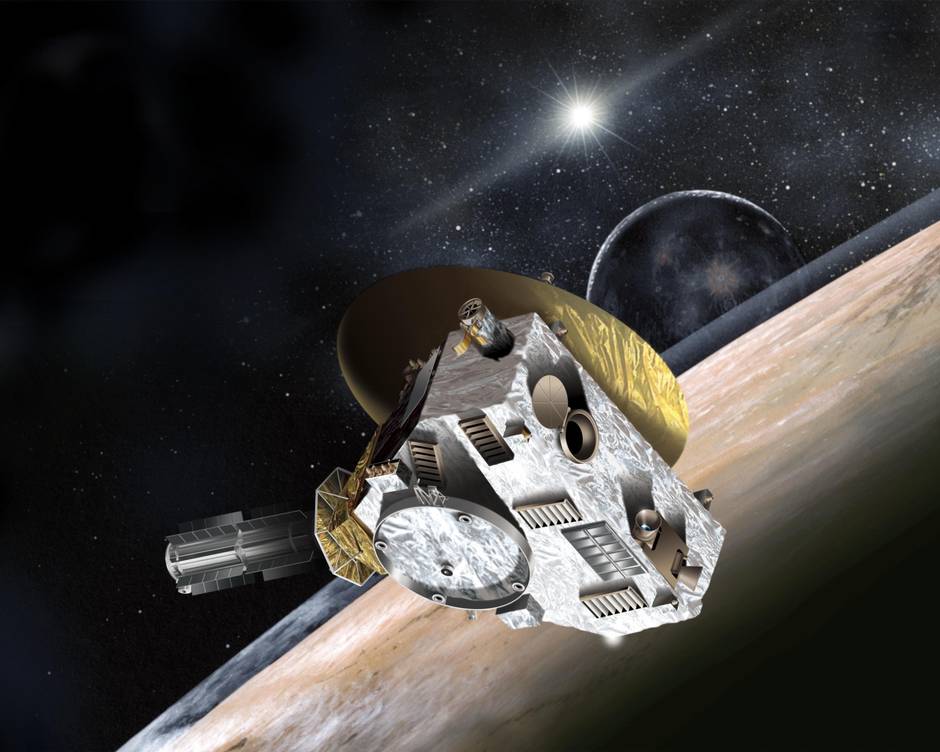

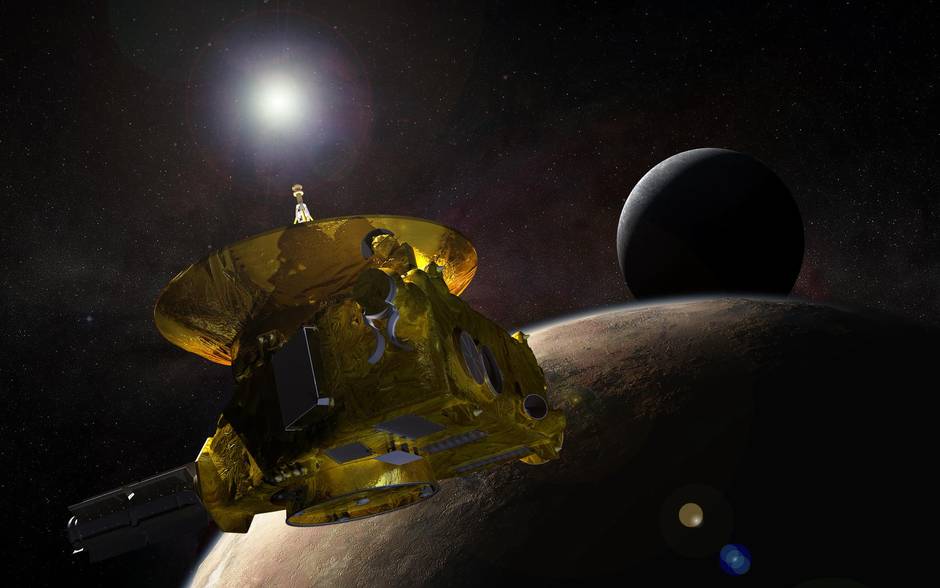

Looking a bit like a grand piano with a satellite dish sitting on top, New Horizons is the fastest spacecraft ever to leave Earth. Even so, it has taken nine-and-a-half years to get to Pluto. And because it has no way to stop or slow itself down once it gets there – that kind of trip requires far more fuel and a much slower approach – its view will be a fleeting one.

Preparations for the encounter have been an exercise in extreme planning. New Horizons is now over 4.75 billion kilometres away from Earth; the round trip signal time for directly communicating with the spacecraft has grown to about nine hours.

That means there’s no practical way for mission controllers to guide the spacecraft in real time. The last day for a course correction was July 4 – coincidentally, the same day that a software glitch silenced New Horizons for a nail-biting 79 minutes. From now on, the encounter will pretty much run on autopilot.

The most valuable data will be gathered during the few hours when New Horizons makes its closest approach, then cuts through Pluto’s shadow and swivels around to see its thin atmosphere, backlit by the Sun.

During that interval, most of the spacecraft’s instruments – a battery of cameras, spectrometers and other detectors – will be taking measurement and capturing images like a busload of frenzied tourists. Scientists expect the spacecraft will gather about 100 times more data during this part of the flyby than it can transmit back to Earth over a single day.

Our first encounter with Pluto will be brief, but the replay will last for months.

The point of all this is not to check off the last box on the “been there” list, says Dr. Stern. Pluto is special. So special that going there will seem less like completing our view of the solar system and more like discovering an entirely new one.

Decades of searching

As many a third grader can tell you, there are eight universally acknowledged planets orbiting the Sun. The first four, including Earth, are small, rocky and close to the centre of the solar system. The next four are big, gaseous and widely spaced. Then there’s Pluto: a world so strange, scientists are still arguing over what it is.

“We are going to the third zone of the solar system, beyond the terrestrial planets, beyond the giant planets…where every discovery we make is is mind-blowing,” says Dr. Stern.

Pluto is not a single destination but several rolled into one. It has a large moon, Charon, that is over half Pluto’s diameter but with a surface brightness and colouration that suggests it’s going to look very different up close. Four smaller moons will provide additional targets for study and New Horizons will also search for signs of rings around Pluto.

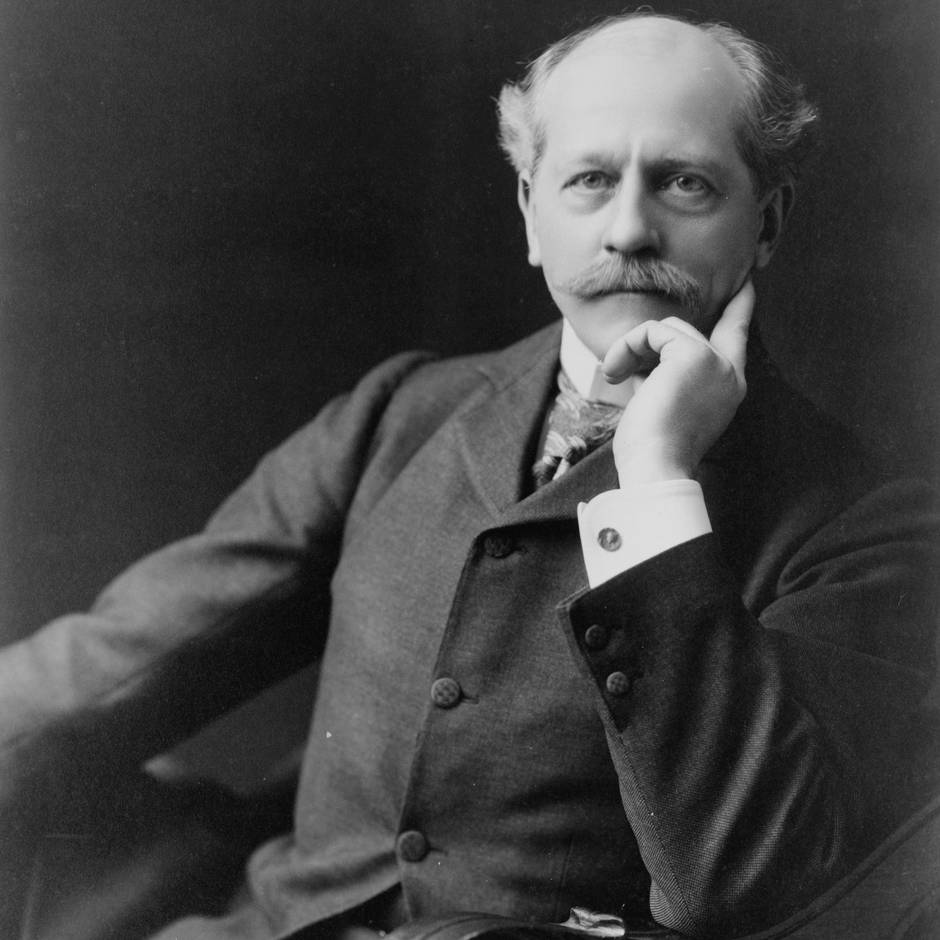

The fact that Pluto was discovered at all can be chalked up to the determination of one man: Percival Lowell, a Boston Brahmin who, in 1894, used his fortune to establish a major astronomical observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona. Today Lowell is best remembered for mistakenly believing he’d discovered canals on Mars, which he attributed to an alien civilization. He was also convinced that the eighth planet – Neptune, discovered in 1846 – was not the end of the solar system. On that score, he would turn out to be absolutely right.

Lowell conducted several searches for a so-called “Planet X” beyond Neptune, but died in 1916 without having found anything. His will stipulated that the hunt should continue; the search resumed in earnest in 1929, when a new telescope was installed at the observatory.

The task fell to Clyde Tombaugh, a 22-year-old with no formal training in astronomy who landed a job at the observatory on the basis of technical skill and sheer enthusiasm. For a year, Tombaugh sifted through hundreds of photographic plates of the night sky, and in February, 1930, he spotted a faint dot jumping back and forth between a pair of images taken of the same star field three days apart. The dot’s motion was exactly what might be expected from a small planet orbiting out beyond Neptune. Barely able to contain his excitement, Tombaugh walked over to the director’s office and boldly announced: “I have found your Planet X.”

The discovery made headlines around the globe. Falconer Madan, head of the Bodelian Library at Oxford University, read the story over breakfast to his 11-year-old granddaughter, Venetia Burney. In a burst of inspiration, she said the new planet should be named after Pluto, god of the underworld. Madan told an astronomer friend, who cabled the idea to Lowell Observatory. Burney’s suggestion stuck. It obeyed the long-standing convention of naming planets after Roman gods, and perhaps more importantly, her proposed name happened to start with Percival Lowell’s initial.

Burney, who died in 2009 at the age of 90, lived to see New Horizons launched to Pluto.

A planet or a whole new realm?

The new world was an oddball from the start. It was far too small and dim to be a gas giant planet, and its eccentric orbit occasionally brought it closer to the Sun than Neptune.

Things got even curiouser in the 1990s, when a number of other faint objects began turning up in telescope searches of the outer edge of the solar system. It appeared that Pluto had company.

Astronomers had a reason for looking. In 1951, Gerard Kuiper, a Dutch American researcher, speculated about the existence of a large population of small, icy bodies beyond the giant planets. To date, a handful of Pluto-sized and over 1,300 smaller bodies have been spotted in what is now called the Kuiper Belt. There may be as many as 70,000 more.

The Kuiper Belt transformed our view of Pluto: it was no longer a loner but instead the most famous example of what is likely to be the most common type of object in our solar system – or any solar system, for that matter. But it also generated a widely publicized debate over how to categorize Pluto. How could it be a planet if there were potentially so many others like it? Where to draw the line?

In 2006, with New Horizons already en route, the International Astronomical Union revoked Pluto’s status as a planet, instead putting it in the newly created category of “dwarf planet.” That decision has never sat well with Dr. Stern, who maintains the demotion doesn’t do justice to Pluto’s size and complexity.

Whatever its official designation, it may be hard not to think of Pluto as a planet once New Horizons reveals it in all its glory. The probe has already sent back images of a mottled, peach coloured orb with tantalizing hints of geological features and surface processes at work. And that’s just the preview.

In 1989, Voyager 2 stunned scientists with its close-up views of Triton, a large moon of Neptune that is thought to be a captured member of the Kuiper Belt. Images revealed a strangely patterned terrain reminiscent of the surface of a cantaloupe, draped in a layer of nitrogen frost and scattered with signs of geysers spewing gas from somewhere below.

Scientists expect Pluto will prove to be every bit as interesting – and their suite of cameras and other instruments are three decades more advanced than anything that was aboard Voyager 2.

During the closest approach, on July 14, “we’re going to be hitting Pluto with everything we have,” says Cathy Olkin, New Horizons deputy project scientist. “That’s going to be show time.”

Ivan Semeniuk is The Globe and Mail’s science reporter. He is covering the flyby of Pluto from mission headquarters at the Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland.