A segment of the Planpincieux glacier is seen on the Italian side of the massif area known to Italians as Monte Bianco - Mont Blanc to the French.Yara Nardi/Reuters

Ice scientists talk about glaciers as if they are animate objects. They call them “frozen rivers.” They “breathe in and breathe out” – that is, they breathe in snow and, when the temperature rises above freezing, breathe out water. Glaciers have personalities and are always on the move.

They live and die, and when they die, the scientists go into a sort of mourning, as if they have lost a dear friend. In August, scientists held a mock funeral for the Okjokull glacier, the first Icelandic glacier whose disappearance has been directly attributed to climate change.

What’s happening to the Arctic’s vanishing glaciers? As melting speeds up, we’ll find out soon

Scientists who monitor the Italian side of Monte Bianco – better known by its French name, Mont Blanc – Western Europe’s highest mountain (4,808 metres), are preparing for the funeral of Planpincieux, a glacier on the northeast stretch of the Mont Blanc massif. This lower part of the medium-sized expanse of Alpine ice has been sliding down the mountain at about 50 centimetres a day – Ferrari speeds by glacier standards. A massive destructive crash may be imminent.

The closed Val Ferret road beneath Planpincieux, on the Italian side.Yara Nardi/Reuters

The road beneath Planpincieux was recently ordered closed by the mayor of Courmayeur, the nearby Italian resort town, and a small number of houses were evacuated. “Its fall is possible any time,” said Fabrizio Troilo, a glacier geologist at the Fondazione Montagna Sicura (Safe Mountain Foundation), the glacier monitoring institute in Courmayeur that has been holding daily news briefings on the glacier’s ability to defy gravity, or lack thereof, since the late September road closing.

By Safe Mountain’s calculations, as much as 250,000 cubic metres of the glacier ice are at risk of collapse. That’s equivalent to the water in more than 100 Olympic-sized swimming pools. The glacier is being monitored by a radar system, mounted in a resort parking lot beneath the glacier, that can detect precise movements day or night, regardless of the weather (the shape of the mountain valleys means any collapsing ice would flow to the left, avoiding the resort).

Safe Mountain began worrying about Planpincieux near the end of August, when geologists spotted a fracture in the glacier. By early October, the fracture was about 150 metres long, 20 metres wide and 10 to 15 metres deep. When The Globe and Mail visited the site then, Planpincieux was, relatively speaking, galloping down the slopes. On Oct. 2, Sector A, roughly the lowest third of the glacier, had moved 80 centimetres in the previous 24 hours, while Sector B, the middle third, had moved 30 centimetres. The top third, Sector C, was stable that day but had shifted 15 centimetres in the previous daily reading.

Alpine glaciers are disappearing at an alarming rate in Italy, France, Switzerland and Austria. Most estimates suggest that 50 per cent of their mass has vanished in the past century, and scientists put the blame on warming temperatures. The immediate threat from a collapsing glacier is fatalities. The Aosta Valley, where Courmayeur is located, and Switzerland have seen several deadly avalanches in recent decades. The good news is that the glaciers most vulnerable to collapse, such as Planpincieux, are being carefully monitored with sophisticated equipment. If they show signs of fragility, any inhabited areas below can be evacuated.

The longer-term dangers of vanishing glaciers are terrifying, too. When glaciers disappear, so does their store of water. The lack of Alpine runoff could trigger a watershed crisis that would damage everything from farming and hydro power to wildlife and tourism. Warming temperatures and waning snowfall are already hurting ski resorts in some parts of the Alps and the Dolomite mountains in Italy’s extreme northeast. The Dolomite resorts are more vulnerable, as they are generally at lower altitudes than those in the Alps.

In an interview, Matthias Huss, professor of glaciology and hydrology at the Swiss university ETH Zurich, said the Alps may be close to “peak water” as glaciers melt and disappear, meaning the runoff volumes that are crucial to agriculture and river replenishment may be just a few years from going into reverse. “In the Alps, it looks like we are close to that tipping point,” he said.

Fabrizio Troilo, a glacier geologist at the Fondazione Montagna Sicura (Safe Mountain Foundation), monitors computer images of the Planpincieux glacier on Sept. 26.Antonio Calanni/The Associated Press

Marco Belfrond holds an old photo of Plancipieux near Courmayeur, a resort town in northern Italy where some homes were evacuated ahead of the glacier's expected collapse.Antonio Calanni/The Associated Press

It turns out the monks in the monastery of the Great St. Bernard Pass, the generally snow-clogged, high-altitude Alpine road that connects Switzerland’s Valais Canton to Italy’s Aosta Valley, were right. For about 200 years, the monks recorded daily high and low temperatures. Safe Mountain learned from them that the average temperature in the pass has climbed about 1.6 degrees.

The figure is roughly consistent with more recent and sophisticated scientific data. Various meteorological studies have concluded that average temperatures in the Alps have climbed two degrees since 1880 with the rise planet-warming carbon dioxide emissions. That’s about twice the global average (a recent report by Environment and Climate Change Canada said the Canadian Arctic has warmed 2.3 degrees since 1948, one of the fastest regional rates in the world).

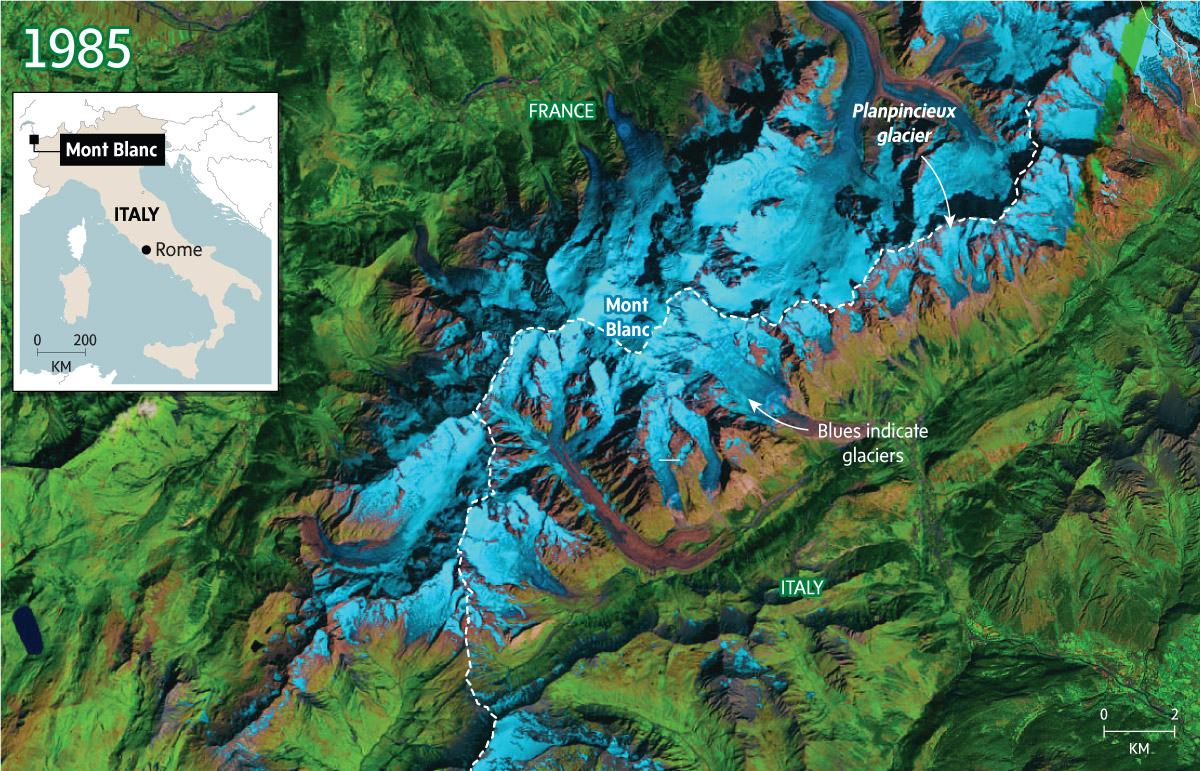

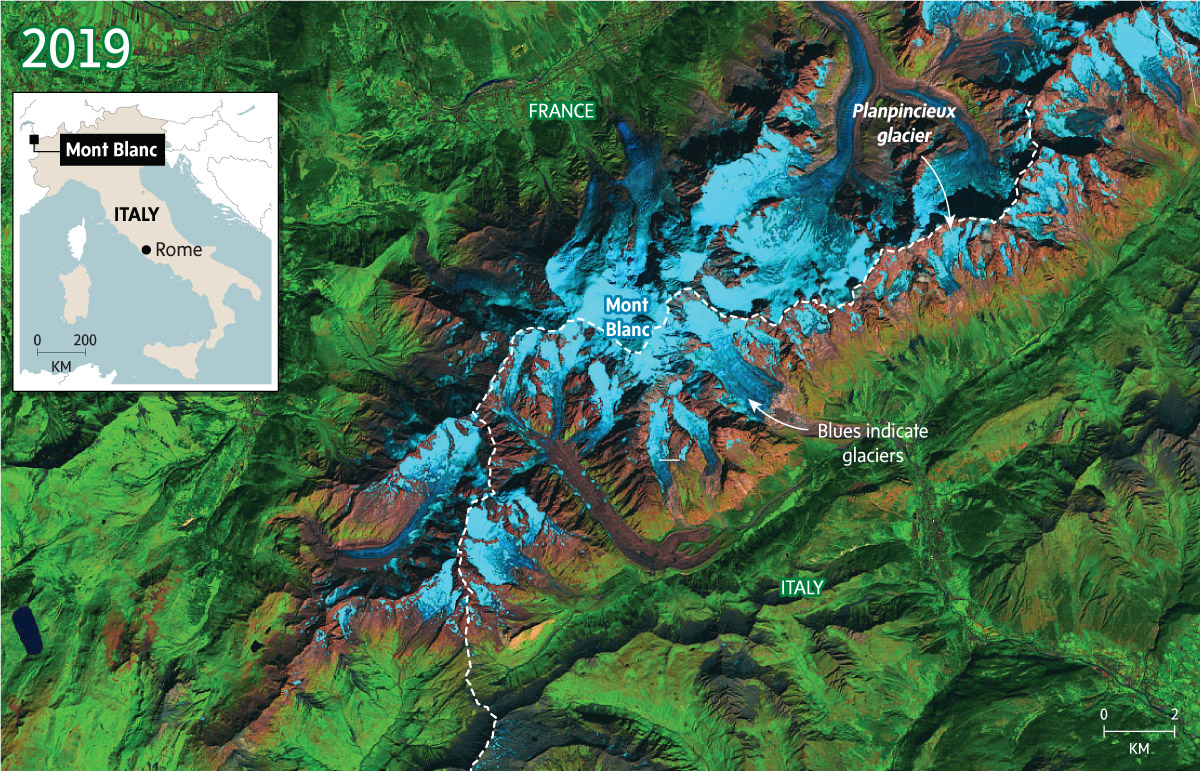

Mont Blanc is turning into the poster boy of mountain climate change. Satellite images obtained by the NASA Earth Observatory show a shocking loss of ice cover along the massif since 1985 alone. Historically, temperatures at the top of Mont Blanc almost never went above the freezing point in the summer. In the past summer, above-zero temperatures were recorded fairly often, with one reading of 7. Those readings came as Europe experienced a record-hot summer. In Gallargues-le-Montueux, near Nimes, in southern France, temperatures peaked at 45.9 degrees – a French record.

Mr. Troilo says glaciers on the Italian side of Mont Blanc and in the Aosta Valley in general – 184 in total, five of which are being closely monitored – have always waxed and waned. Records show that in the 1940s and 1950s they experienced a rapid amount of ice loss, followed by a small expansion in the 1960s and 1970s. “But since the mid-1980s, it’s been continuous loss,” he said. “There has been no inversion of the trend."

The trend has been noticed by local residents. “I remember when I was a kid that the ice would come all the way down the mountain,” said Franco Di Domato, 46, an electrician. “We were used to the ice coming and going, but now it’s mostly in retreat. Even if the winter precipitation is high, the [rising] summer temperatures melt the glaciers’ snow cover.”

Ice is vanishing everywhere in Italy. Until the 1990s, small glaciers could be found as far south as Gran Sasso (2,912 metres) in the Apennine range east of Rome, about 700 kilometres south of the Alps. Renato Colucci, a glaciologist at Italy’s National Research Council, has called many of the glaciers in Italy and Austria “the walking dead” in media interviews. The World Glacier Monitoring Service says the area covered by Alpine glaciers dropped from 4,500 square kilometres in 1850 to just under 2,300 square kilometres in 2000. Today’s glacier coverage figure is probably far less. Glaciologists think glaciers on Alpine mountains of less than 4,000 metres are unlikely to survive over the long term.

Glaciologist Matthias Huss speaks at a mourning ceremony for the disappearing Pizol glacier in Switzerland on Sept. 22.Denis Balibouse/Reuters

Prof. Huss, the Swiss glaciologist, says glaciers are vital to the watersheds of mountain regions and their downstream rivers, such as the Po in Northern Italy and the Rhône in southeast France, whose waters irrigate important agricultural regions. Once the glaciers have shrunk considerably, or are gone, their natural ability to take the hard edge off late-summer dry periods will go, too. He says that a quarter of the water at the mouths of the Po and the Rhône in August comes from glacier runoff.

“Glaciers release water when it is needed most, during the hot, dry periods,” he said. “That’s a very important role. Once the glaciers are gone, we will need to replace their water-storage capacity, maybe by building more dams.”

The scientists at Safe Mountain and the residents of Courmayeur and villages and hamlets nearby are on death watch for the Planpincieux glacier. By mid-October, its lower reaches were still sliding down the mountain fairly quickly – the Oct. 13 reading was 30 centimetres; on Oct. 25, it was 45. It could crash at any time, although the chances of its destruction can only recede as the fall temperatures drop.

In the meantime, the road beneath the glacier remains closed. The locals are well aware of the deadly power of avalanches, especially when they come loaded with rock debris. In January, 1997, a huge avalanche roared down from the Brenva glacier just beyond Courmayeur, destroying everything its path, including 200-year-old trees. Two skiers were killed, and 10 injured.

“For Planpincieux, the risk is between now and the winter freeze,” said Valerio Segor, director of natural risk management for the Aosta Valley. “This glacier is no longer immune to gravity.”

Yara Nardi/Reuters

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Eric Reguly

Eric Reguly