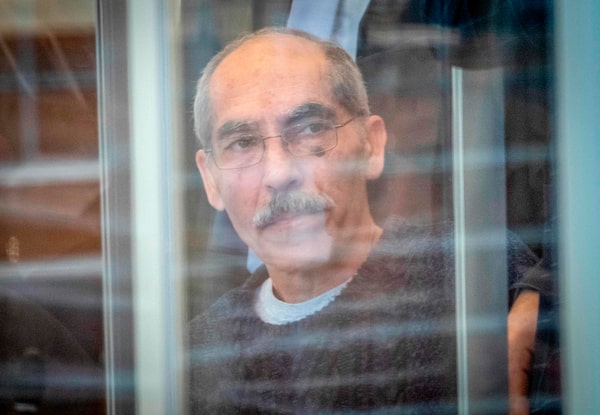

Anwar Raslan arrives at court in Koblenz, western Germany, for an unprecedented trial on state-sponsored torture in Syria, on April 23, 2020.THOMAS LOHNES/AFP/Getty Images

At first, Anwar al-Bunni did not recognize the man who had jailed him in Syria many years before.

Remarkably, the two Syrians had been assigned six years ago to live in the same refugee settlement on the edge of Berlin. When they would pass each other on the street, Mr. al-Bunni, a human-rights lawyer and outspoken opponent of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime, felt he knew the other man’s face, though he couldn’t remember where from.

“I ignored him and he ignored me,” Mr. al-Bunni recalled this week. Faces from the past were out of context in his new life in Germany.

He only connected the dots when a Syrian friend called him with some curious news: “Did you know that Anwar Raslan is in the same camp as you are?” the friend asked.

That was the familiar stranger on the street: Anwar Raslan, whom Mr. al-Bunni remembered as the head of investigations in the notorious Branch 251 of Syria’s General Intelligence Directorate, a key cog in the Assad regime’s security apparatus – a place where torture was rampant. Mr. al-Bunni said it was Mr. Raslan who oversaw his arrest and imprisonment in 2006 after he had spoken out in favour of democracy in the country.

His chance encounter with his former jailer in Berlin led to a remarkable moment Thursday, when Mr. Raslan heard the charges against him as they were read out to a courtroom in the German city of Koblenz. The 57-year-old was accused of crimes against humanity, as well as multiple counts of murder, rape and sexual assault in connection with the deaths of 58 people who are alleged to have died under his supervision. Clad in a sweater and wearing spectacles, Mr. Raslan kept a tight-jawed silence throughout the first day of the trial.

Syrian human rights lawyer Anwar al-Bunni is seen in his office in Berlin, on April 9, 2020.JOHN MACDOUGALL/AFP/Getty Images

Eyad al-Gharib, a 43-year-old who is alleged to have worked for Mr. Raslan in Branch 251, stood as his co-defendant at the hearing, accused of aiding and abetting crimes against humanity.

The lawyers for the accused declined to speak to reporters who were present. The proceedings are expected to last at least a year – longer if the defence seeks additional adjournments because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The trial is a key moment not just for the pursuit of justice in Syria but also for the work of the Commission for International Justice and Accountability, a Canadian-funded non-governmental organization – led by former war-crimes prosecutor William Wiley – that has been working with anti-Assad rebels since 2012 to assemble evidence against the regime in anticipation of such trials. Evidence collected by the CIJA is expected to be presented in the Koblenz court, which will then rule on its admissibility.

It’s also the highest-profile application to date of a 2002 German law that gives its courts universal jurisdiction over certain crimes, including crimes against humanity, regardless of where they were committed.

“For victims of the case – the victims of torture and other crimes against humanity – it’s their first chance to confront their perpetrators in a court of law. That’s extraordinarily meaningful to our clients,” said Steve Kostas, a senior legal officer with the Open Society Justice Initiative, which is representing six former prisoners of Branch 251.

The beginning of the trial marks a rare victory in recent years for those who have been battling the Assad regime in the country’s nine-year-old civil war.

What began as a pro-democracy uprising quickly descended into a bitter sectarian conflict that has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives. Mr. al-Assad, with the help of his Russian and Iranian allies, has recaptured most of the country. Many of the areas that remain outside the regime’s grasp are controlled by either the Turkish military or jihadist groups.

Thursday was also a sweet moment for Mr. al-Bunni, who first spoke to The Globe and Mail in October, 2005, seven months before his arrest.

He had been in hiding for 10 days, worried that he would be arrested on trumped-up charges as punishment for his decision to sign a document known as the Damascus Declaration, which criticized the Assad regime as “totalitarian” and called for the country to make a peaceful transition to democracy.

He still had the look of a wanted man, unshaven and dishevelled. But he wanted to talk about the findings of a United Nations report that had just been released and pointed the finger at Mr. al-Assad’s inner circle for the February, 2005, assassination of former Lebanese prime minister Rafik Hariri.

“This type of regime cannot be accepted in the world after this,” Mr. al-Bunni said then in the kitchen of his Damascus apartment, the kitchen sink running to make it more difficult for anyone to eavesdrop electronically on the conversation. “Regimes like this have no future.”

The next day, he got a warning that he had again gone too far in his criticism. He was attacked by men he believed were pro-regime thugs on the street and hospitalized. His brother called and said Mr. al-Bunni wanted The Globe to come to the hospital and interview him again, to demonstrate that he hadn’t been intimidated. The Globe declined, explaining that it would be a bad idea for everyone.

Mr. al-Bunni was jailed in May, 2006, and later sentenced to five years in prison for the crimes of belonging to an illegal group and “spreading false or exaggerated news that could weaken national morale.” Unbowed, he told the court he was proud of his pro-democracy work. “I didn’t commit any crime. This sentence is to shut me up and to stop the effort to expose human-rights violations in Syria.”

His sentence expired in May, 2011, just as Syria’s uprising was devolving into full-blown civil war. In 2014, he fled to Germany, which led to his chance encounter with Mr. Raslan – who had defected from the regime in 2012 – in the Marienfelde refugee settlement. “Luckily or not, he was in the same town, in the next building,” Mr. al-Bunni said in a telephone interview Wednesday.

Despite Mr. Raslan’s change of heart, some in the Syrian opposition aren’t ready to forgive his past. Mr. al-Bunni said he is determined to see the entire “machine” – as he calls the Assad regime – brought to justice. “My enemy is a criminal system. [An] infernal machine that arrested, tortured and killed. Anwar [Raslan] is part of this machine,” he said. “I want to expose and condemn it … and expose those responsible.”

He said he had spent eight months helping German prosecutors build their case against Mr. Raslan, a man who had long seemed beyond the reach of such justice. Eventually, he predicted, Mr. al-Assad too would face his moment in court.

Mr. al-Bunni was on a train during the interview, en route to Koblenz to attend Mr. Raslan’s trial. The pandemic meant there would be reduced seating in the courtroom, but Mr. al-Bunni wanted to be one of those in attendance.

Mr. Raslan’s trial, he said, was “an important stage in our work – and in my life.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Mark MacKinnon

Mark MacKinnon