They had more than a year to prepare for the highest-profile sexual-assault trial in Canada in recent memory. But as it unfolded, prosecutors were blindsided again and again by evidence in possession of Jian Ghomeshi's defence.

"You kicked my ass last night and that makes me want to fuck your brains out," complainant Lucy DeCoutere said in an e-mail to the former CBC Radio host written just hours after he allegedly sexually assaulted her in 2003 – although she had told police she'd had only incidental contact with him afterward.

And so the defence turned the tables. On Day 1, the trial morphed – in the view of some law professors and sex-assault crisis centres – into an old-fashioned flaying of Ms. DeCoutere and the other two alleged victims who testified. "This is and remains a trial about Mr. Ghomeshi's conduct," Ms. DeCoutere's lawyer, Gillian Hnatiw, said, taking to the courthouse steps. And to the annals of myths and stereotypes involving women and sex assault, they say, was added a new one: that there is a right way and a wrong way to behave after a sexual assault.

In a case keenly followed on Twitter and in law schools, justice itself was on trial for how it balances the treatment of alleged victims against the presumption of innocence. But the trial some people expected, focused on Mr. Ghomeshi's conduct, never materialized. Instead, one after another, the women came under an onslaught of evidence about their own behaviour and inconsistent statements.

"It is absolutely astonishing how poorly the Crown and the police prepared the prosecution," said Toronto criminal lawyer Christophe Preobrazenski, who was not involved in the case.

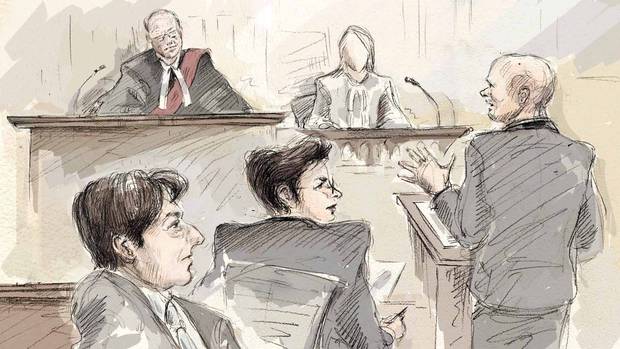

In this courtroom sketch, witness Lucy DeCoutere, right, is cross-examined by defence lawyer Marie Henein, centre, as Jian Ghomeshi, bottom left, and Justice William Horkins listen in court in Toronto on Friday, Feb. 5, 2016.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Alexandra Newbould

But the question is what they could have done differently. Crown attorneys speak bluntly to sex-assault victims about the need to tell everything they know, according to Rick Woodburn, the president of the Canadian Association of Crown Counsel. They meet several times before the trial, to build a rapport and prepare victims for what they will face in the witness box. (Sometimes, they even take them to an empty courtroom to sit in a witness box.) The Crown lawyers have all the notes and videotapes prepared by the investigating officers, usually from a highly specialized sexual-assault unit. And an investigating officer joins the meetings.

"One of the most important things I say is, 'Look, the accused knows everything we know. But we don't know everything the accused knows,'" Mr. Woodburn, a Halifax prosecutor, told The Globe.

"'We only know what you're telling us. So if there's something else, you really have to dig in your mind, you have to go back through your e-mail, you've got to look at your phone. Because this stuff is going to come up and grab us.'"

Something did come up and grab the prosecution in this case: e-mails, letters and photographs, some more than a decade old, in Mr. Ghomeshi's possession. The result: One of Toronto's ablest criminal defence lawyers, Marie Henein, a protégé of the late Eddie Greenspan, was now in the driver's seat.

The first complainant testified she couldn't bear to hear Mr. Ghomeshi's voice or see his face after the alleged assault. But then Ms. Henein showed the courtroom a picture the complainant later sent Mr. Ghomeshi of herself in a bikini. Then came Ms. DeCoutere – reading, at Ms. Henein's request, from a letter she had written Mr. Ghomeshi: "I love your hands." And then the third complainant, shortly before testifying, revealing to police that she later engaged in sexual activity with Mr. Ghomeshi at her house – although she had initially told them she saw him only in public because she was afraid of him.

The Crown has had a constitutional obligation since a 1991 Supreme Court ruling to disclose relevant evidence to the defence; but the defence does not need to show its hand in return (unless it has an alibi as the defence). "At least as far as the defence is concerned, it can still sometimes be trial by ambush," criminal defence lawyer Eric Gottardi of Vancouver said.

There was another surprise, too: 5,000 electronic messages between Ms. DeCoutere and another alleged victim. "A defence lawyer's dream," a senior lawyer calls the trove. Because the 5,000 messages created a possibility of collusion, Crown attorney Michael Callaghan could not argue, as he had intended, that, because the women's stories were similar, an inference could be drawn that they were true.

The alleged victims' credibility and reliability – or honesty and accuracy – were suddenly under open attack by Ms. Henein, armed with evidence.

"You just wait and see how well the witness withstands it," a retired Ontario prosecutor said in an interview, describing how Crowns try to limit the damage in such situations. "Do you want to go back in and dig any further or just leave it? Can you call any further evidence? Are you going to start calling psychologists? It's a hard one to be calling your expert after the fact to prop up your witnesses." The Crown countered in this case by adding a witness, late in the trial, who said that Ms. DeCoutere had told her about being assaulted.

Jian Ghomeshi makes his way through a mob of media with his lawyer Marie Henein at a Toronto court on Nov. 26, 2014. It was the former CBC host’s first time in public after being fired by the broadcaster.

Darren Calabrese/THE CANADIAN PRESS

Compounding the credibility problem, not only Ms. DeCoutere but a second alleged victim had retained lawyers – making it more difficult to claim they didn't understand the process. (Victims have no legal "standing" in criminal courts in Canada; the only parties are the Crown and the defence.) "A person in my position would not be acting ethically if they in any way suggested that a person hide information, change their information or in any way not be truthful, accurate or forthcoming," lawyer Jacob Jesin, who represented the first woman to testify, said in an interview.

But why do some alleged victims not tell everything to police investigators, even in sworn statements, which are deemed so reliable they can be used in court even if their source dies or refuses to testify? Hilla Kerner, a spokeswoman for the Vancouver Rape Relief and Women's Shelter, cautions that even trying to answer that question is "exactly what the defence wants us to do. They want the court and the public to question women's behaviour."

But then she offered an answer. "After a traumatic event, our memory is not operating in a consistent, comprehensive way."

Whether women continue to be attracted to their attacker is irrelevant, she said. "They are really trying to make sense of something that is hard to make sense of. Sometimes we hope he will understand and offer some remorse. We are human. We have mixed feelings."

If the trial was a showcase for Canada's modern rules for sexual-assault trials, aimed at encouraging victims to come forward to police, some felt that the system's failings were on display. The federal rape-shield law generally forbids questions about an alleged victim's sexual history. (Parliament passed the law in 1983, the Supreme Court struck it down in 1991 as unfair to accused individuals and then Parliament revised and passed it again in 1992.) University of Calgary law professor Jennifer Koshan argues that a complainant's discussions of sex should be treated like her sexual experience, and kept out of trials.

"We should not consider her more likely to have consented on the occasion in question, or to be less credible, simply because she has engaged in sexualized communications with the accused after the fact," she wrote in a blog during the Ghomeshi trial. "Our focus must still be on whether there was consent at the time of the alleged incident."

The trial put a spotlight on the vigorous cross-examination of sex-assault complainants.

Dirk Derstine, a Toronto criminal defence lawyer, asks whether people who make sex-assault allegations should be immune from a challenging cross-examination. "I would say no, otherwise we proceed from an assumption of guilt. We can't have people coming before the court be presumed to be telling the truth. That would stand the entire system of justice on its head."

The consequences for an individual convicted of sexual assault are enormous, Ottawa criminal defence lawyer Michael Edelson said. "They're on the sexual offenders registry, sometimes for life. They can't get employment. They have restrictions on their ability to travel. They're giving their DNA. They are literally walking around with a scarlet letter in the community."

In her summation to Ontario provincial Justice William Horkins, Ms. Henein said it was the complainants who made their post-offence conduct relevant by claiming they were too traumatized by the sexual assaults to have any further contact with Mr. Ghomeshi. "It was a lie," she said. Quoting the American jurist John Wigmore, she called cross-examination "the greatest legal engine for discovery of truth ever invented." Mr. Callaghan said the three women remained, however, "unshaken in their allegations."

Justice Horkins, in a 2008 sexual-assault case in which testimony from an accused man and two alleged victims were completely at odds, explained that such cases are not a simple credibility contest; the Crown must prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt.

"I consider it understandable that both consciously and unconsciously some essentially honest witnesses may edit or 'spin' their recollection of past events in the hope of being believed on the central truth of their evidence," he wrote in that case. "Such behaviour will not always be fatal to the credibility of the witness," but when combined with "lack of candour, this may contribute to uncertainty as to the general sincerity of the witness and contribute to the creation of a reasonable doubt." He acquitted the man in that case.

Violence against women not about women’s behaviour: lawyer in Ghomeshi case

1:35