0 minute

0 minute

Here is a Scottish landscape to soothe the tortured soul. One small window looks west toward a wild and craggy bluff, its base wrapped in silky green – a golf course. The other turns the centre of Edinburgh, less than five kilometres away, into a setting for a fairy tale: a rugged coastline by the sea; tall church spires; a dark, mysterious castle atop a steep cliff.

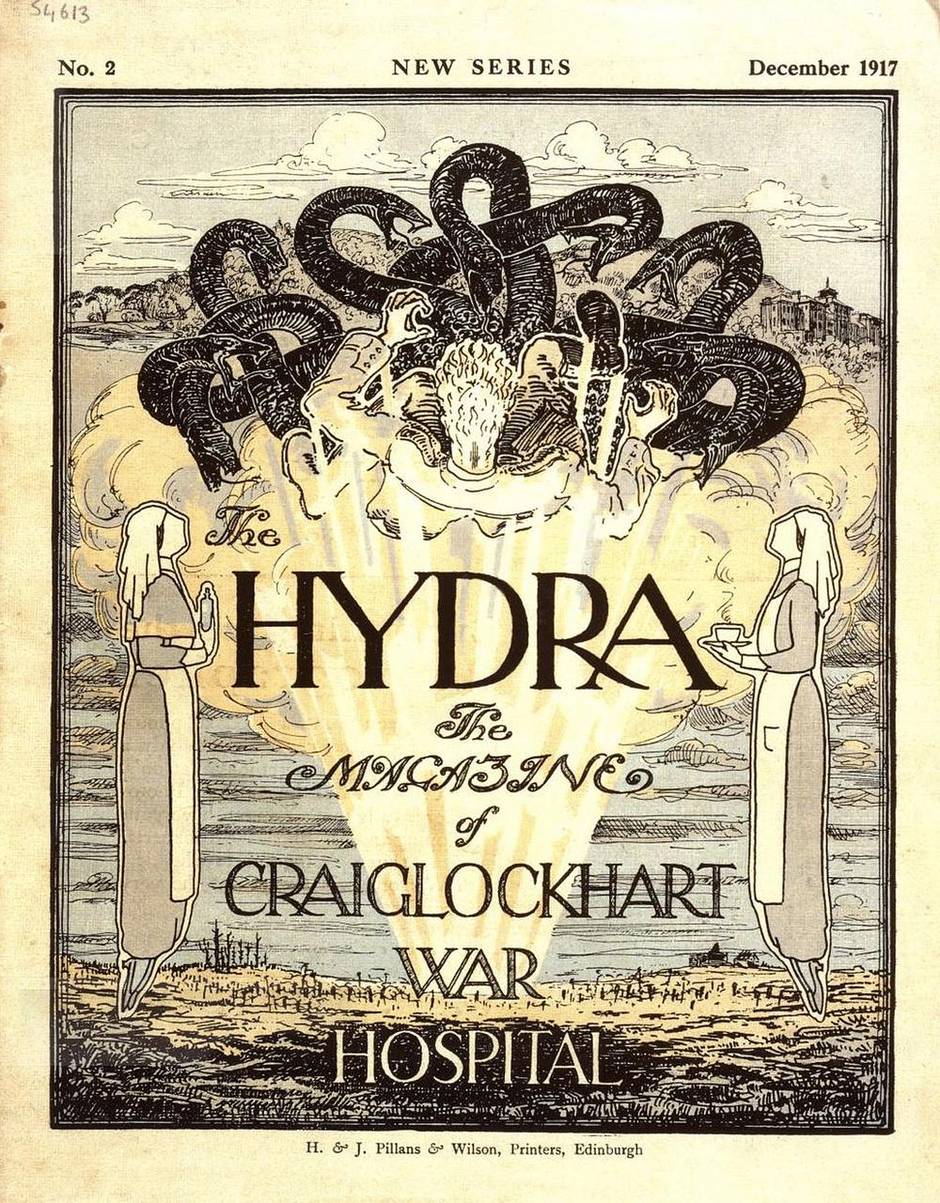

This is the view from the room Siegfried Sassoon is believed to have occupied in 1917. But his was not a happy stay – the famed poet was forced to come to the imposing Italianate building then on the outskirts of Edinburgh. He called the place “Dottyville.”

Built 40 years earlier as a medical spa, Craiglockhart War Hospital had been commandeered to battle the great mystery illness of the Great War: shell shock.

Today, photographs of soldiers taken just after they’d enlisted are a study in Victorian innocence – they had no idea what they would face. One minute, young men schooled in heroic, Tennysonian visions of warfare were erect atop their horses, gallant and cheerful, as crowds waved them off to the front. The next, they were in hospitals with bewildering symptoms – insomnia, nightmares, palpitations, headaches, tremors, partial paralysis, and amnesia – sometimes unable to talk or see, curled up in the fetal position whenever a loud noise sounded.

Shell shock was culture shock – it turned postwar Western sensibility into what U.S. literary scholar Sarah Stoeckl has called an “imaginative No Man’s Land, unable to find consolation in previous modes of understanding but uncertain how to move forward.”

It had powerful repercussions throughout society, largely because its cruel paradox was unimaginable.

At the turn of the 20th century, in an age of stolid Victorian beliefs, many based on class assumptions, who would have thought that courage may contain fragility; that our most noble instincts – a determination to serve, to be selfless – can be undercut by forces that are just as willful but not within our control? There was still so much yet to learn about both mind and body.

As we mark Remembrance Day in the centenary year of the start of the First World War – with Canadians now deployed in Iraq and Kuwait to join the international campaign against the insurgent Islamic State – we might ask ourselves: How much has changed in our understanding of war trauma?

Shell shock threatened the existing medical and institutional approach to mental illness, laying the groundwork for modern psychiatric practice in the process. One of the more progressive psychologists, W.H.R. Rivers, who treated patients at Craiglockhart, wrote that the war was “a vast crucible in which all of our preconceived views concerning human nature have been tested.” But the diverse opinions about how to treat the ailment reflected the ambivalence of the medical establishment.

One hundred years later, much of that ambivalence remains. Millions of dollars are spent in research initiatives around the world to unravel the complexity of physical, psychological and emotional trauma – in the general population as well as among veterans diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other war-related psychiatric problems.

Today, the public has at least some grasp of what’s at stake. Back then, the reaction was confusion, rejection – or worse.

Roughly 10,000 Canadians were treated for shell shock during the Great War, according to the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. But the total number who suffered was likely much greater. Many affected soldiers may have not applied for a pension for neurological or psychological disorders – one way to assess the prevalence of them; others may have recovered by the war’s end. Many may have felt too ashamed to acknowledge it at all.

My great-grandfather, William Barnard Evans, was one. Having volunteered in Montreal, he served on the Western Front for 17 months, before suffering a breakdown he never discussed or sought treatment for. His war diaries simply stop after he noted that he had asked for a leave as lieutenant-colonel of his battalion, and his commanding officer recommended a staff job. After the war, he returned to Canada and resumed, as best he could, his former life.

Others were less fortunate. Lieutenant-Colonel Sam Sharpe, a member of Parliament decorated for his service both at Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele, was sent home after falling prey to shell shock. A few days later, he leaped to his death from a window at Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal.

‘Modernity gone wrong’

Shell shock precipitated what one academic called “a crisis of masculinity,” finding expression in the literary trope of the anguished male anti-hero. But more than that, shell shock fuelled unease about the conflict and became a “symbol of modernity gone wrong,” observes Joanna Bourke, a professor of history at the University of London in England.

It would help make the war what she calls “the greatest rupture of the 20th century.”

This was a war in which explosives could reduce men “to particles so small that only the wind carried them,” as Sebastian Faulks wrote in his celebrated 1993 novel, Birdsong. Much about it was new. And at first, some wondered if some dark force, unleashed by the industrialization of war, could be penetrating the brains of men. The machine gun, which had been invented in 1884 – with the firepower of 60 to 100 rifles – dominated the battlefield for the first time. Explosive shells rained down on the men with a blast force never seen before. The largely volunteer army had little training or psychological preparation for the stresses of artillery bombardment, which kept soldiers constantly on edge. And, of course, the terror weapon of gas was used for the first time.

In addition to the strain brought on by new kinds of weaponry, soldiers didn’t do tours of duty as they do now. They went to war and were expected to see it through, with periodic rest periods behind the lines. One thing that had changed dramatically was the duration of battles – they went on for weeks, sometimes months. In his book, The Face of Battle, military historian John Keegan points out that 50 years earlier, the bloodiest battle of the U.S. Civil War – Gettysburg – was over in just three days.

The first reports of incapacitated, shell-shocked men returning to England came in September, 1914, barely more than a month after the start of the war. They were met with puzzlement about the “strange malady,” creating a powerful tension between old-school military leaders, who were widely skeptical about its veracity, and medical professionals, who had to figure out how to treat it.

Initially, some military physicians tried to associate shell shock with physical or organic injury to the brain or central nervous system. They diagnosed a concussion caused by proximity to exploding shells.

Toxins such as carbon monoxide, released from shells, could be a cause, or changes in atmospheric pressure, resulting from proximity to an explosion, could produce microscopic brain hemorrhage, they believed.

The term “shell shock,” which had come into usage through word of mouth by soldiers to express the emotional disturbance of modern war, was first used in medical circles by Charles S. Myers, a Cambridge University laboratory psychologist, who wrote a paper about it in the influential medical journal The Lancet in 1915.

But soon, it became clear that organic (or “commotional”) injury wasn’t the only possible cause. Ancillary staff and nurses who were nowhere near exploding shells often reported similar symptoms. Patients with no family history of mental illness – or “hereditary taint” as they put it – were affected.

Hard-line military leaders, schooled in traditional warfare, dismissed its significance as “malingering,” a discipline problem or character weakness, punishable often by court martial and death by firing squad.

Uncharitable social beliefs were often invoked. “They have an awful class view that ordinary soldiers don’t recognize fear because they’re just too stupid,” explains Edgar Jones, professor of military psychiatry at King’s College London. He points out that Charles McMoran Wilson, a regimental doctor awarded the Military Cross in 1916, later wrote in his book, The Anatomy of Courage, that “the best soldiers are the peasant farmers because they live on the land and are accustomed to killing animals.” But when they break down, they are “plainly worthless fellows.”

William Walton, a 26-year-old sergeant in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, was a victim of the first wave of shell shock during what’s known as the Great Retreat from Mons – when allied forces made an arduous 320-kilometre trek under continuous bombardment. Arrested four months after deserting in November, 1914, he explained that he was suffering from nervous exhaustion, but his superiors didn’t buy it. He was court-martialled and became the 14th soldier executed for desertion since the retreat began.

‘An infection in the ranks’

As far back as ancient Greece, a form of war neurosis has been documented. Herodotus described a soldier in the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC “deprived of his sight, though wounded in no part of his body.” The Romans, too, found that their bravest men, the legionary eagle-bearers, sometimes broke down on the battlefield. In 1678, Swiss physician, Johannes Hofer called it “nostalgia,” suggesting that the disturbed sleep, weakness and anxiety was similar to “the pain which the sick person feels because he is not in his native land.” It was seen in the Napoleonic Wars, when it was considered a form of insanity, according to Anthony Babington in his book, Shell Shock, A History of the Changing Attitudes to War Neurosis; and again in the U.S. Civil War. An alternate diagnosis in the 19th century – in particular during the Crimean War – was that it was “soldier’s heart,” explains Prof. Jones, co-author of Shell Shock to PTSD, Military Psychiatry from 1900 to the Gulf War.

“They thought it was a physical illness affecting the heart. Palpitations. Chest pain … It’s how you feel when you’re frightened and your heart beats faster. It’s difficult to catch your breath,” he adds. As it was seen as a physical cardiac illness, it brought no shame.

But the opening war of the modern age was different. It would be the first to have significant psychological ramifications for one simple reason – scale. And the perfect, horrific storm for shell shock arrived with the failure of the Battle of the Somme in 1916. After more than 600,000 men in the Allied forces had been killed, wounded or gone missing, after 141 seemingly endless days of fighting, it could be ignored no longer. Close to 40 per cent of the casualties at the Somme suffered from emotional disorders.

Shell shock was a full-blown military crisis, seen as “an infection in the ranks,” according to military historian Tim Cook, the author of Shock Troops: Canadians Fighting the Great War, 1917-1918. And it could cost the allies the war.

Prison-like conditions

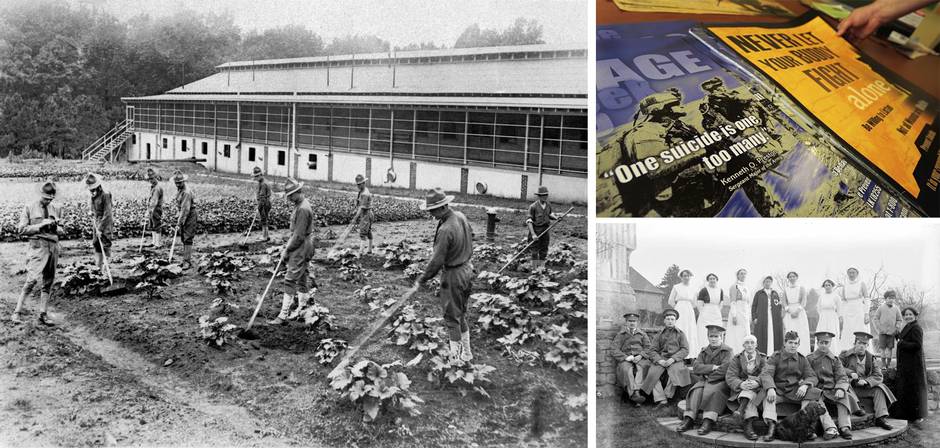

Neurologists were dispatched to the battlefields in France to investigate, and the increasing incidence of shell shock led to creative new theories among physicians in England – Charles Myers being one of them. Special hospitals were set up – by the end of war, there were 23 in the United Kingdom, where many Canadian soldiers were treated. Public outcry that shell-shocked soldiers would be sent off to asylums – the old system for handling mental illnesses, in which someone was certified insane, and sent for indeterminate amounts of time to institutions, run by local counties, in often prison-like, deplorable conditions – forced changes in institutional structure. But they weren’t made just to appease the concerns of families who wanted proper care for their loved ones and to avoid the stigma of having them incarcerated in asylums. The goal of the War Office was to get the men well enough to return to the battlefield.

That imperative – this was a war of attrition, after all; the army with the most men would likely win – was also behind the decision first to grant (in 1916) and, a year later, remove the awarding of “wound stripes” to victims of shell shock. Worn on a man’s left sleeve between the cuff and his elbow and made from strips of gold braid, wound stripes were an innovation – “a badge of heroism,” Prof. Jones explains. As an understanding of shell shock developed, and doctors saw that, in some cases, there were no physical causes for it, they deemed it an illness rather than a wound.

“You wouldn’t get a wound stripe if you got influenza, for example,” he adds, explaining that the phenomenon called “secondary gain” – the idea that a psychiatric patient wouldn’t be encouraged to get well if he was rewarded for being ill – also came into play.

Class was a mediating factor in the treatment, hospitalization and even nomenclature of the diagnosis. “Privates suffered ‘hysteria’ … whereas officers were said to suffer from ‘anxiety neuroses,’ or ‘neurasthenia,’ which has a much higher status,” says Prof. Bourke, the historian. Officers were sent to separate hospitals and often to spa-like country estates and private homes that were adapted for medical and therapeutic use. Ambivalence in the military establishment never completely abated. (Even at the end of the war, shell-shocked soldiers were being court-martialled and shot for desertion. The last was a Canadian, who had enlisted in 1914, been admitted to hospital in 1917, and still sent back to the front. He deserted in November, 1918.)

Medical thinking, however, was less rigid, Prof. Jones notes. “For the first time, a psychiatric diagnosis attracts the attention of thousands of doctors, some of whom wouldn’t normally work in psychiatry.”

One was Frederick Mott, a scientific researcher in neuropathology, who investigated the most severe cases of shell shock at the Maudsley Hospital in London, where approximately 12,000 patients were treated between 1916 and 1919.

An “atmosphere of cure” – involving rest, fresh air, warm baths, good food, and diversion – was his approach. Introspection was discouraged. One of the wards that remains today is a handsome building with big windows that overlook what was once a garden where the men planted vegetables, raised chickens, built an ornamental fountain, and laid out tennis courts. A hut was erected – still standing – for them to occupy themselves with woodworking and metalwork.

By 1916, Mott had identified three categories of shell shock: those who have a head wound and therefore suffer a physical effect of concussion; robust men who had simply endured horrific experiences; and the largest group – those who had an “inborn timorous or neurotic disposition” because of childhood trauma or hereditary vulnerability, which made them more likely to break down.

“It’s a combination of your genetics, your upbringing and what happens to you, and that position is pretty well established by the end of the war,” explains Prof. Jones, whose office is at the Maudsley.

The great insight was that every man, no matter his background, his education, his class, had a breaking point. As Mott himself wrote in 1917, “even the strongest man will succumb, and a shell bursting near may produce a sudden loss of consciousness, not by concussion or commotion, but by acting as the ‘last straw’ on an utterly exhausted nervous system.”

But if that was the prevailing sentiment by the end of the war, there were two extremes of psychiatric thought and treatment during it.

One treatment: shame

At one end was Lewis Yealland, a Canadian-born psychiatrist educated at the University of Western Ontario who qualified to practise medicine 1912 and came to Britain three years later to treat shell shock. Most of his patients were from the ranks, and he gained a reputation for facilitating a rapid recovery – and for controversy. He believed that war neurosis was within conscious control of soldiers; and he set out to solve the problem with shaming, a blatant use of paternalistic power and authority (he was known to threaten court martial) and often the application of electric-shock therapy in a locked and darkened room.

In one infamous case, Yealland treated a 24-year-old private, who had been mute for nine months after enduring many of the war’s worst campaigns. “A man who has gone through so many battles should have better control of himself,” Yealland reportedly told him. Strapped down with his mouth opened using a tongue depressor, he had electrical current applied to his pharynx and throat, “hot plates” inserted into his mouth, and the tip of his tongue burned with a cigarette. After four hours of this, the soldier managed to mumble a few words, and then was required to say “thank you” to Yealland.

At the other extreme was Rivers, a psychologist, physiologist and anthropologist among the first in England to support the psychoanalytic work of Sigmund Freud (which one pillar of the psychiatric establishment dismissed as “probably applicable to the people on the Austrian and German frontiers, but not to virile, sport-loving, open-air people like the British”).

Rivers’s understanding of shell shock reflected antiquated class assumptions. He believed it was beyond the control of officers, as their mental makeup was more “complex and varied” than that of men in the ranks, and their storied stiff-upper-lip mentality was part of the problem. But his treatment was progressive, stressing what he called “autognosis” or self-understanding through conversation, hypnosis and psychoanalysis. In some cases, after the war had ended, he encouraged the men to return to the scene of the trauma in France.

It was to him that Second Lieutenant Siegfried Sassoon was sent in the summer of 1917 amid intense media scrutiny, which reveals the ignorance and shame associated with the illness. From a prominent family, Sassoon had left Cambridge (without a degree) to lead a gentlemanly life of reading, writing and shooting. He served with the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, earning the nickname Mad Jack for his bravery after capturing an enemy trench single-handedly. He fought in the Battle of the Somme, and was awarded the Military Cross, but grew disillusioned. His brother had been killed at Gallipoli, and the Somme, billed as the Great Advance, “had been nothing of the kind,” he wrote, noting that his battalion was rendered “almost unrecognizable by heavy casualties.”

Back in England in 1917 after being hit by a sniper in the Battle of Arras, he became truly discontented, throwing the ribbon from his Military Cross (“my absurd decoration”) into the River Mersey and watching it float away “as if aware of its own futility.”

He also kept company with pacifists and reportedly hallucinated that he saw dead soldiers lying in the street. But his shell-shock diagnosis came after he decided to bring to Parliament his “Soldier’s Declaration,” saying the war was being “deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it.” Court martial was threatened – he was still an officer, after all – causing friend and fellow poet Robert Graves, who had served with him at the Somme, to intervene. He persuaded a medical board that Sassoon was suffering from “neurasthenia” and should be admitted to Craiglockhart. The media went wild, suggesting that he was invoking class privilege.

Sassoon himself wouldn’t admit to having broken down and, at Craiglockhart, often complained about “dotty” fellow patients wailing in their sleep. Rivers gave him a room of his own and much kindly personal attention. Their interesting and unusual relationship is the subject of Pat Barker’s 1991 novel, Regeneration.

Treated for an “anti-war complex,” Sassoon wrote and played golf. He also met Wilfred Owen, another convalescing soldier-poet, who recalled Sassoon encouraging him to “sweat your guts out writing poetry.” After four months at the hospital, Sassoon returned to active service – to save face, he suggested later. Wounded again in 1918, he was granted sick leave for the duration. Owen, too, returned to the front after 127 days at Craiglockhart – and was killed one week before the war ended.

The Lost Generation

The shooting stopped in November, 1918, with nine million dead or missing; but rising from it came the spectre of the Lost Generation. “Men were hidden inside their homes by their families, who were ashamed they had broken down,” explains Joanna Bourke, whose books include The Intimate History of Killing and The Story of Pain.

At officer hospitals such as Craiglockhart, “there was a deliberate destruction of medical records to protect [the men’s] reputation because of stigma,” Prof. Jones notes. Sexual impotence was a widespread symptom, according to some reports. “If the essence of manliness was not to complain, then shell shock was the body language of masculine complaint, a disguised male protest not only against the war but against the concept of ‘manliness’ itself,” writes feminist culture critic Elaine Showalter in her book about depression, The Female Malady: Women, Madness and the English Culture 1830-1980.

In medical circles, Freudian talk therapy gained ground in part because the medical establishment had to devise new ways of dealing with the psychological wounds of outpatients – clinics for whom were a postwar innovation brought on by the number of recovering shell-shock victims. Rivers, who died unexpectedly in 1922, proposed an alternative view of Freudian psychoneurosis, based on his experience with shell-shock patients. He dismissed Freud’s sexual theories as the driving factors of psychoneurosis, and suggested that, rather than sex, conflict between self-preservation and a desire to fulfill duty caused the mental breakdown.

As Prof. Jones explains, “Shell shock was a diagnosis that could save your life. It means you leave the battlefield. They’re not faking it. They’re wearing out. And there will be an unconscious wish to have the diagnosis. These are unconsciously created symptoms … and the unconscious drive would be, ‘This is the only way I can survive.’”

The debate continues

Doctors who had treated shell-shock patients during the war returned to regular practice once it was over. Some of the knowledge about stress-related mental illnesses was applied to workplace problems, but it wasn’t until the Second World War that medical science had to grapple again with shell shock on a large scale. Experts found they still had a lot to learn.

To help soldiers as quickly as possible, psychological treatment centres were set up near the action. But the military still didn’t recognize that “people can’t go on forever and that everyone ultimately will break down, however well-trained and courageous,” Prof. Jones says. That understanding didn’t dawn until about 1943 or 1944, “when commanders, fighter pilots and captains of escort vessels, who were decorated, start saying, ‘I can’t do this any more.’”

It was only after Vietnam that the term PTSD was adopted. Psychiatric problems were handled well during that war, but when veterans returned, they often suffered from nervousness, sleeplessness and irritability, thought to be exacerbated by the anti-war environment at home. Finally, in 1980, PTSD was officially accepted as a disease – only after doctors lobbied the American Psychiatric Association because they had treated similar symptoms in civilians.

Study into PTSD, which concerns more psychological symptoms as opposed to physical ones such as tremors and heart palpitations, is ongoing. In 2009, U.S. researchers reported the results of a two-year, $10-million study on the effects of blast force on the brain. Its key finding: that the blast-exposed brain remains structurally intact but suffers injury by inflammation – verifying some of the initial thoughts about shell shock . Emory University in Atlanta, meanwhile, has harnessed virtual-reality therapy to help veterans suffering from emotional disorders.

Still, questions remain, as does controversy in the military. In 2008, Canada introduced the Sacrifice Medal for wounds and death “under honourable circumstances,” including PTSD, only after public protest – as the U.S. recently decided to do for its Purple Heart.

We stand in an interesting moment, looking back 100 years, and looking forward, as Canada sends soldiers to the Middle East once again. We should pause not just in remembrance, but in thoughtfulness as well. We should think about the cultural attitudes that will greet any who return with psychological trauma. In the past, they’ve been romanticized: seen as cautionary reminders that human beings are not designed for war. Which doesn’t help. Despite memoirs about PTSD and efforts to destigmatize it, many sufferers still feel undertreated and shameful over something they cannot control.

We love cultural scripts about bravery and sacrifice; national myths are built on them. But if soldiers have limits, so do we in our ability to understand what they go through after a war. The conflict between the conscious and unconscious, the paradox of courage and fragility, is locked in the mind of the sufferer.

Where it remains a mystery.

Sarah Hampson is a Globe and Mail feature writer.