of China

Little Jie, in a yellow cap and grey hoodie, darts out the doors of his school and across the road to where his mother is waiting to pick him up for lunch. He jumps up and down in excitement. “My favourite food is French fries,” the nine-year-old says. His favourite period at school is xiake, when class is dismissed. “Because after xiake, you can have fun outside.”

While his mother, Lu Cuiping, steams vegetables inside their small apartment on the outskirts of Beijing, he brings out a Lego navy frigate, which in his hands becomes a Chinese vessel mounting assaults on the enemy. “I want to be a military expert,” he says, “researching naval weapons.”

“He’s very patriotic,” Ms. Lu says. Usually, “the enemy is Japan. … But sometimes he will aim at the family-planning committee.”

For most Chinese, a child who dreams of attacking the state would be horrifying. But Little Jie is not Chinese – at least not according to the country in which he was born and lives. To China, he is no one. A ghost.

Forty-five years ago, China inaugurated an era of population control, amid fears that too many people would bring catastrophe. In 1980, it officially announced a national one-child policy, forcibly limiting the size of families. But there have been, inevitably, second (and, rarely, third and fourth) children: children who go unrecognized by the government, have no official identity – who are left to live outside the institutions of regulated society. Little Jie is one of them.

Since 1971, China has seen a total of 336 million abortions, completed 196 million sterilizations, and inserted 403 million intrauterine devices.

More difficult to count are the ghosts: the ones who were born, but have no official status. China’s 2010 census estimated that there were 13 million people without official documentation – a population almost the size of Ontario’s.

China’s one-child policy has been called the “most spectacular demographic experiment in history,” and “one of the most draconian examples of government social engineering ever seen.” It has also been, according to the best available evidence, a failure even on its own terms.

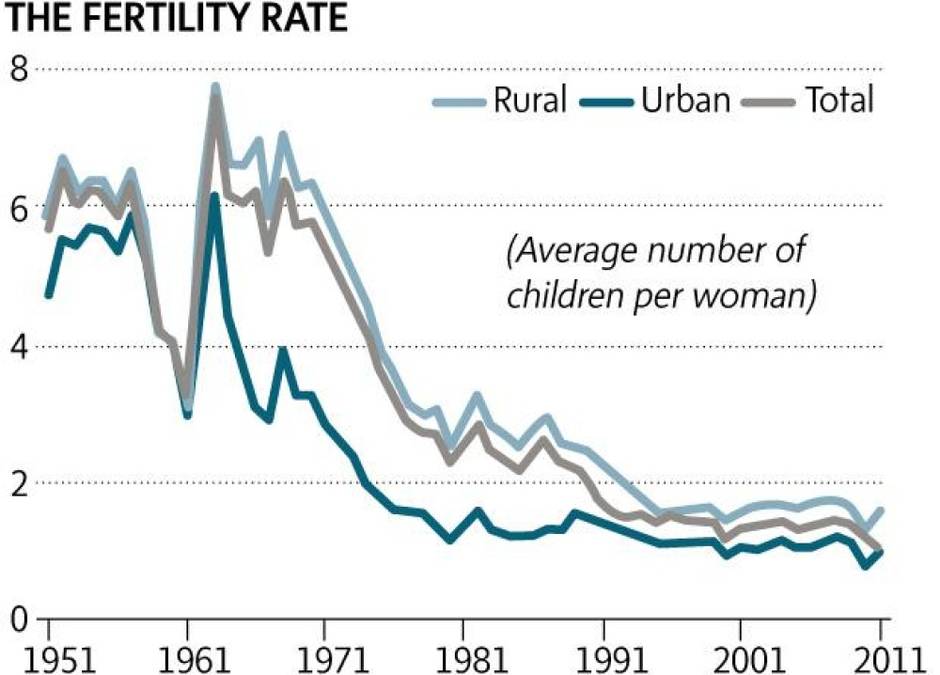

It did little to alter birth rates – much of the decline had come earlier, under a 1970s-era two-child policy. Meanwhile, the most significant purported economic benefit of the one-child rule – that women who bear fewer children would be better able to join the work force and boost national productivity – is being offset by the mess China faces today, due to its vast forgone population.

While population restrictions fundamentally reshaped China, the one-child policy itself, which coincided with a time of growing wealth that brought natural declines in birth rates, didn’t do China much good. Instead, by artificially cutting families to just one child, it brought decades of pain — and the millions of ghosts it has created are still without official home or respite.

Life as a ghost

The foundation of Chinese civic life is the hukou, a maroon-and-gold household-registration document. It is a form of identity used to control people’s movements inside the country, set up by the Communist regime, and similar to systems used in Soviet Russia and imperial China. With it, a person can secure a national-identification card, attend school, access basic medical services, find a place to live, board a bus or train, open a bank account, get a job, and secure a passport. Without it, each of those things becomes difficult and, for those with too little money or too few connections, often impossible.

There is, for those with fat enough wallets, a way around it. Although families are limited to one child, Chinese authorities allow them to simply pay a fine – that, if unpaid, grows over time – for any extra offspring; the wealthy, in other words, can buy for themselves as many children as they please. Pay the fine, and your child gets a hukou, becoming indistinguishable from any other child. Those with more modest salaries, meanwhile, struggle with sums so punitive that they are effectively impossible to pay.

The last time Ms. Lu checked, in 2012, her fine was at 333,466 yuan (about $67,500). Before Ms. Lu lost her job recently, she earned 2,000 yuan a month (about $400). It would take 166 months – nearly 14 years – of her entire salary to pay off the fine.

She lost that job, in part because she turned down her boss’s request to move to a new location, a neighbourhood where she knew she would not find a school with a sympathetic administrator – the only way Little Jie (the name his mother calls him) is able to attend elementary school right now. Even if they stay put, his education won’t last: Little Jie won’t be allowed to write the standardized exam that provides entry to middle school.

Ms. Lu, who is 42, has grown consumed by a desperation that she has cursed her child merely by giving birth to him. She tried to sell a kidney to raise money to pay the government fine, but was told she was too old. “I have thought about robbing a bank,” she says. “But I don’t have those kinds of skills.”

For the most part, she hides her feelings from Little Jie, but he already feels his situation keenly. When he found out about bird flu, he stopped eating chicken, afraid it would make him sick and that a hospital wouldn’t help him without proper documentation. For his last birthday, he begged his mother not to get presents or a cake. At the grocery store, he tells her not to buy anything unless it’s on sale. He wants her to save money in hopes of paying the fine.

Over a lunch of shredded potato with chili peppers, bok choi and dry tofu, Little Jie suggests another solution. “Maybe you can marry a big official, so he can kill Mr. Ji,” he says, with childlike naïveté. In Chinese, “ji” is the first syllable in “family-planning office.”

None of this was supposed to happen.

In 1993, Ms. Lu had her first child, a daughter. Six years later, she divorced; her husband got custody of their child. Then, she fell in love again, and although they didn’t marry, she became pregnant. She was thrilled – a new child might help assuage the pain from the girl she had lost. Fears of violating the one-child policy did not enter her mind; she has Mongolian ancestry, and minorities are largely exempt from birth restrictions. Besides, her first child had already been taken away.

But after Little Jie was born, she was asked to show marriage credentials. She didn’t have any. A court eventually deemed her legally married to Little Jie’s father, who himself had lost custody of another child from a previous marriage. “So the family-planning office judged that [Little Jie] is my third kid,” Ms. Lu says.

She is so crushed by the thought that she has ruined her son’s life, she is willing to give him up if it can give him a better one. “Find me some family to adopt him, so he can go to school,” she says. “Otherwise, I’m going to destroy him.”

A new population theory

There are lions of history inside the curving halls of Beijing’s Millennium Monument: 40 men and women cast in life size, each a towering contributor to the country’s culture. Confucius and Sun Tzu are here, as are those who invented paper and movable-type printing, founded Taoism, pioneered railroads and performed new styles of opera. Among them is Ma Yinchu, a man born in 1882 and identified as an economist, educator and demographer.

“Ma advocated birth control for China,” the plaque reads. To many, he is the father of the one-child policy.

Mr. Ma’s own family is horrified at that association. It “patently was not Ma Yinchu’s theory,” says Ma Size, his grandson, during an interview in Beijing, where he showed photos of the sprawling courtyard house in which he grew up with his famed ancestor. “Actually, my grandfather’s demography theory called for families to have two children,” he says. “And he opposed abortion. He saw it both as the killing of a life and bad for women’s health.”

Ma Yinchu’s story is, nonetheless, in many ways the backdrop to the grand narrative of China’s attempts to control its population.

When the Communists took over in 1949, Mr. Ma was among China’s most prominent academic voices. He served as president of Peking University and was friends with Zhou Enlai, the first premier of the People’s Republic of China. And Mr. Ma was worried about babies. The first census of Communist China, in 1953, counted 600 million people, a shocking rise from 450 million in 1947. The prospect of the population cresting a billion was suddenly possible – and frightening. If China wanted to make each of its people wealthy, Mr. Ma reasoned, it would be easier to do so if there were fewer of them. Besides, he added, China didn’t have the land to feed so many new mouths.

As a fix, he proposed a “new population theory” that embraced the widespread use of child-restraint propaganda, encouraged birth control, offered incentives for small families, and called for bureaucratic dissuasion of large families.

China was not the only country wrestling with these questions. For different reasons, the U.S. military began to sound the alarm in the 1950s, worried that burgeoning Asian populations would provide fertile ground for Communist revolutions. In the 1960s, after the global population passed 3 billion, environmental concerns also arose internationally. The United Nations and the World Bank both advocated population control, the latter deeming unchecked population growth a detriment to economic expansion. Richard Nixon called it a “world problem which no country can ignore.”

The world took notice, often in problematic ways. India oversaw a campaign that forcibly sterilized 8 million women in the 1970s. (Coerced sterilization remains a concern there today.) Bangladesh paid women to be sterilized. Indonesia set reproductive targets for local leaders to enforce.

For a long time, China had resisted these ideas. When Mr. Ma unveiled his theory to the public in 1957, it was met with hostility; he was called “a lifelong opponent of the Party, socialism, and Marxism-Leninism.” Mao Zedong famously believed that more workers meant more production, and that a big enough population would make the country invincible in war. “The more people there are, the stronger we are,” he once said.

But just over two decades later, when China’s population surpassed 800 million, Beijing began to warm to the idea of taking action, and in 1971, China set explicit goals for reducing the growth rate. Under the slogan “Later, longer and fewer,” the country set rules for delaying marriage (with specific age requirements for men and women) and required couples to wait at least four years after the birth of their first child before having a second. In cities, families were cut off at two children. Officials had already started handing out birth control for free in the 1960s.

Then, in the 1970s, great numbers of Chinese women were forced to use intrauterine devices. Compliance was not optional. A campaign of forced abortions and sterilizations was also launched, though not implemented to the extent it would be later on.

Propaganda played a part, too. People were told about their local community’s financial situation, as a way of creating peer pressure on couples not to burden the system with additional children. A famous 1979 state-newspaper editorial suggested the country had erred grievously by ignoring Mr. Ma. Its headline: One Individual Wrongly Criticized, 300 Million More Births.

The next year, the full-fledged one-child policy was introduced, amid fears – based on faulty science – that without more drastic action, China’s population risked growing to 4 billion, and its people risked running out of water and food. At the time, medical groups rallied around a slogan of “having only one child for the revolution.”

Immediately, the use of coercive tactics spiked. In 1983 alone, 20.7 million Chinese women were sterilized, and there were 14.4-million abortions. Many were not done by choice.

Losing faith in the system

Mr. Feng was a senior engineer at a rocket-research institute. It was a coveted job, a high position at a state-run organization in Beijing. He and his wife tried for years to have a child, eventually resorting to in-vitro fertilization, at a cost of roughly $10,000. They had a girl in 2009, and thought they were done.

Then his wife, against all odds, got pregnant again, this time naturally. And their lives began to unravel.

“I knew for certain that I was going to lose my job. But then we talked about it and thought, ‘Maybe we can have the baby in secret,’” says Mr. Feng, 42, who asked that only his surname be used because of continuing sensitivities around violating the one-child policy. That decision launched his family into a cat-and-mouse game with colleagues, friends and neighbours that would shake his loyalty to the very system that had once brought him such success.

As his wife began to show, she stayed inside. But someone – he still doesn’t know who – reported the couple to his local work unit, who called Mr. Feng to ask about the pregnancy. He denied it to them, and then denied it to the leader of his research institute, who asked as well. “They said, ‘Okay, then call your wife here. Let’s have a look.’”

He lied again. “My wife is not in Beijing,” he said, “she’s already gone back to Nanjing,” her hometown. The stakes were high: As an employee of a state-owned firm, he had to confirm each year that there were no additional pregnancies in his family. If he was found to break the rules, he, his boss and all his colleagues would forfeit their bonuses and, potentially, chances at promotion. Mr. Feng made plans to have his wife stay with a friend in a village outside the city. Within 48 hours of the first phone call, he had taken the afternoon off work to drive her there.

On the way, his cellphone rang. Another work leader wanted to meet. “Come back quickly,” he said. Mr. Feng stopped at a small public park where his wife could hide, and drove back to work. He was told to pledge in writing that his wife was not pregnant, and that he would have to accept all possible consequences if she was. He signed.

That night Mr. Feng drove his wife and daughter away. More than a week passed, and he started to breathe easy. Then he got another call from a boss at work. This time, they needed proof that his wife was not pregnant. Mr. Feng offered to provide it from afar, then had his sister-in-law pose as his wife for the test.

The ruse didn’t work for long. Ten days later, a colleague came by and said it was imperative that his wife return to Beijing. When Mr. Feng said that wasn’t possible, the colleague revealed he had already booked two tickets to Nanjing, saying: “You and I will go to see your wife and get her tested at a hospital. If it’s negative, okay. But if it’s positive, she has to have an abortion.”

The tickets were booked for that night.

“There was nothing I could do to hide any more. I said it was impossible to take him to Nanjing with me. I said I would accept whatever decisions they made.”

His colleague got up and printed a resignation letter, saying Mr. Feng was leaving for personal reasons. Mr. Feng signed it; they took his security pass, and that same afternoon he was gone.

At home, neighbourhood authorities visited daily, pressing for Ms. Feng to obtain an abortion. When their second child, a son, was eventually born, he was told it would cost 370,000 yuan – $75,000 – to buy him proper registration. “We don’t have that kind of money,” he recalls telling them. “I can’t even raise that by selling my house.”

Mr. Feng had spent his life chasing success in the Chinese system, from his days as university student-union chairman onward. But the experience of having a second child was deeply jarring. “Isn’t it natural for humans to have a child,” he asks, “and isn’t it reasonable to do so?”

“I used to be a person who believed we shouldn’t make trouble for the party,” he says, in an interview at a cafeteria outside his new workplace – a private company where he works as a software engineer. Neither the benefits nor the job title match his old status, but at least he has work. “But this has made me rethink not only the family-planning policy but also broader issues such as people’s rights and the construction of our civil society. I started rethinking the whole system.”

His is a common sense of disenfranchisement.

Second children are conceived and born for all sorts of reasons. Some parents want a larger family badly enough that they consciously flout the law. Often, though, second pregnancies are accidental, and carried to term by families that cannot countenance an abortion, and then cannot afford the fine that follows forgoing one. The policy poses little obstacle for the wealthy, some of whom simply skip the system altogether by giving birth in places like Hong Kong, the United States and Britain. It’s the middle and lower classes who find themselves without hukou. Unable to game the system, their experiences often breed a dark cynicism.

A failure on its own terms

China credits the one-child policy with avoiding 400 million births. Without it, family-planning officials have said, the population would be 30 per cent larger than it is today. Outside China, green groups have called it the country’s single greatest environmental contribution to the planet’s health, while economists have suggested it has contributed greatly to the immense wealth the country has amassed in recent decades.

But demographers have been less certain: Some 70 per cent of the decrease in China’s child-bearing rates actually came in the years before the one-child policy was launched, under previous efforts at curbing family size through less-severe restrictions, such as delaying marriage and second children. And although the 1970s-era two-child policy led to unmistakeable human-rights violations, the one-child policy constituted a major increase in birth restrictions and fast accelerated the pace of forced abortions and sterilizations. It also lasted far longer than a single decade – and much longer than needed, according to demographers, who point to China’s Asian neighbours, where a rise in wealth has by itself led to much lower birth rates.

Some of the most striking criticisms of the policy come from Chinese academics who have looked at the whether the policy really did prevent 400 million births; some suggest a more accurate number would be 100 million. “Most of the births averted, if any, were due to the rapid fertility decline of [the 1970s], not to the one-child policy that came afterward,” demographers Wang Feng, Yong Cai and Baochang Gu wrote in a recent paper. History, the demographers concluded, will “likely view this policy as a very costly blunder.”

The only explanation they can conjure for the policy’s continued existence is bureaucratic: Maintaining the one-child regime now employs so many officials – in the hundreds of thousands, perhaps more – that China hasn’t been willing to put them out of work.

A desire to avoid catastrophic population growth initially lay behind China’s strict controls. But after nearly a half-century of artificially altering birth rates, China has created long-term demographic problems that are prompting a rethink of the entire grand experiment. Though estimates vary, the population is expected to peak between 2020 and 2030 at around 1.45 billion. By 2030, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences expects China to be the greyest society on Earth: Today, the country counts almost five taxpayers for each person drawing a pension; by 2030, the ratio will fall to roughly 2:1.

Academics and blue-collar workers alike fret over China’s growing old before it grows rich; at the same time, the country’s GDP expansion has already slowed to its lowest level in 24 years, and is expected to continue dropping. China has reached a “post-Yinchu era,” Mu Guangzong, who is with the Institute of Population Research at Peking University, recently wrote. The country stands at the “crossroads of history” and needs to depart from “the myths of ‘overpopulation’ and ‘strong family planning’ ” as soon as possible.

As a result, China is reconsidering the one-child policy so seriously that many believe it is only a matter of time before Beijing does away with birth restrictions altogether; in some cities, there is already talk among officials of baby bonuses to spur more children. The country has resisted any explicit concession of wrongdoing, saying in 2013 only that the policy will be “adjusted and improved step by step.” At that time, it was relaxed to allow families two children if even just one parent is a single child (before then, both had to be single children to be allowed a second child).

In publicly grappling with the problems, China’s elites have tacitly acknowledged that the one-child policy has gone too far. What they haven’t done is grandfather in changes that would alleviate the pain felt by the policy’s most acute victims: the ghosts.

‘Social maintenance fees’

Max Wong, 48, was a long-time pastor, a man for whom the notion of abortion was anathema. So when his wife unexpectedly got pregnant a second time, and then a third, there was never a question they would carry through to birth. What he didn’t expect was the upheaval such births would cause.

He was fired after their third child was born. “Since, as a pastor, you have broken the Chinese law, you are not a good example,” he was told by other church leaders. At home, his second son was retreating into himself, telling his family, “Because I have no identification, I don’t want people to know me.” The depression was serious enough that Mr. Wong returned to his old hometown to look into paying the fine – it would be cheaper there. He was told to pay 100,000 yuan, or roughly $20,000, up front for his children’s documentation. He was told “you are going to get it soon.”

That was more than a year ago. He still hasn’t received anything, though he expects to soon. He is critical of the system. The penalties, he believes, are a convenient way for officials to pad their own pockets. For him, that helps explain why the policy has been so persistent. “That money becomes grey income for the local government,” he says.

In response to written questions submitted by The Globe and Mail, China’s Health and Family Planning Commission replied that local officials must make public their rules about one-child-policy fines, as well as information about how much money they collect. The law requires local officials to submit those fines – which China calls a “social maintenance fee” – to the national treasury, although they are then returned to local budgets. As a result, there remains an incentive for neighbourhood officials to use second children as a revenue source. It’s not small change: In 2012, a report that tallied such fees in two-thirds of China’s provinces found that they had brought in $2.6-billion in fines from violators of the policy.

Despite the shifting attitudes in the Chinese government, in its response to the Globe the commission defended the necessity of maintaining family restrictions, writing that “some of the fundamental realities of China are not changing, such as the country’s large population and the heavy pressure it places on economic and social development.” The commission also said that the fine would be assessed at “three times or less” the average per-capita disposable income in a given area, per parent.

The Globe and Mail interviewed a half-dozen parents who, together, had eight “ghost” children. Those parents told us the fines were up to 14 times the average annual salary in a given area, and that they rise every year.

Raine Ma, a 34-year-old accountant, has seen the fine for her second child – a daughter who is now 6 – increase from 300,000 yuan ($61,000) in 2012, to 430,000 ($87,000) in 2014. That’s nearly 10 times the 45,052-yuan average annual income last year in her neighbourhood of Beijing.

Paying it would leave her family destitute for years. “This policy is not fair,” she says. “Isn’t giving birth a basic right?” Besides, she points out, neither Bill Gates, Warren Buffett – nor even Mao Zedong or current president Xi Jinping – were first-born children. “How many outstanding people were planned out of existence?” she asks. “I think the policy right now is just to control people like us, living decent and honest lives.”

The Globe also asked the Commission about the prospect for further easing restrictions. There is “no timetable to make it wide open for a second child for every family,” came the reply. And “cancelling the social maintenance system would be unfair to the people who have answered the call of the state and strictly obeyed the family-planning policy.”

A world passing her by

From the small confines of Li Xue’s chilly house in downtown Beijing, talk of reform seems awfully distant. Over her lifetime, a new China has crept up around her, but for Ms. Li little has changed in the 21 years since she was born as a second child. The loosening of China’s one-child policy has done little to give legal standing to the “ghosts.” Officially, she still does not exist.

Ms. Li did not come from wealth. Her father cut leather at a state-owned company, for 100 yuan a month. When her mother became pregnant a second time, with Ms. Li, a cooking injury left her with an infection that, doctors said, prevented her from having an abortion. Her mother, who had polio as a baby, lost her job at a collectively owned neighbourhood company when Ms. Li was born. At the time, her father was told to pay a 5,000-yuan fine for her birth – 50 times his annual salary. “If we pay this penalty, who will pay for my family to live?” he asked them.

Ms. Li was never vaccinated, and has no formal education. As a child, she raided neighbours’ old books and gave herself a basic education, teaching herself math, reading and writing. She traces the subsequent years through a sheaf of documents that scrupulously document the attempts she and her parents made to reverse her situation: official notes, letters and petitions that catalogue a lifetime of frustration, with countless trips to police stations, the family-planning office and courts – a grand game of jurisdictional Ping-Pong.

She cannot buy basic medicines, which require an ID card. She cannot board a train or long-distance bus without proper documentation; her life has been confined to just the few kilometres around her house.

Her status, or lack thereof, has also meant social exclusion. “Parents would like to have their kids socialize with people who are well-educated or have good scores, instead of me, who hasn’t studied at all,” she says. Others are nervous to be with her, too, since for years her local neighbourhood committee, seeing her as a troublemaker, has kept watch, making her look suspicious. She knows this because in 2009 her father found a paper in the trash showing the 10 people – a mix of police and neighbours – organized into shifts, 24 hours a day, to monitor the family’s comings and goings. “Basically, I don’t have friends,” she says.

She hasn’t dated, either, because she knows no one would want to marry a “black child,” as the Chinese call ghosts. Besides, dating belongs to talk of a future she tries not to contemplate. “I don’t think too much about dreams,” she says.

More recently, she has spent much of her time caring for her ailing parents – cooking food and accompanying them on doctors’ visits. Her father’s weak health was compounded by the times he was roughed up for advocating for his daughter, and last year he was hospitalized. When Ms. Li spoke with The Globe and Mail in the fall, the hospital called to say others were in greater need of the ventilator that had supported him. It was pulled out, leaving Ms. Li “afraid that without the ventilator, my dad will die.”

A few days later, he passed away. With him went his 1,260 yuan ($255) in monthly state support. In its place was roughly 15,000 yuan ($3,000) in medical debt.

Sitting on the spartan queen-sized bed she shares with her mother, Ms. Li is largely stoic as she recounts the details of her many indignities. But as she contemplates her father, her voice grows pinched. “He suffered so much for me,” she says. Tears roll down her face. “I feel like I should never have been born.”

Among the papers she has collected are decades-old internal family-planning-commission documents, dog-eared from years of being pored over, including one from 1988 with rules that suggest Ms. Li should have been awarded a hukou, and that her parents should bear the punishment, not her. Ms. Li has poured much of her time into studying law, researching her case and handwriting legal petitions, but has failed to convince a court to side with her. She has lost two lawsuits against the local family- planning office.

Still, she holds on to hope. She plans to file a new appeal in late March. And in January, her life suddenly took a turn upward. A foreigner in Beijing hired her as a waitress at a new restaurant. She didn’t know how to make coffee or mix a drink. It’s an illegal job, and she whispers about it at home, lest her neighbours find out. But for now, she is making money that she can use to buy her mother medicine. “My burden,” she says, “has lifted a little.”