To his school friends, he was Lee, or on his Facebook page, Kim Chol. To the customs officers looking at his fake passports, he was Pang Xiong, a Chinese name that translates to "Fat Bear."

To more recent acquaintances, he was simply Mister Kim, the studied bon vivant with the sushi restaurant who thought Donald Trump was crazy, occasionally travelled with a pair of female bodyguards and warned friends that his brother was out to kill him.

But his death, amid bizarre circumstances in Malaysia, exposed a series of plot twists that has, so far, included an aspiring Vietnamese singer alleged to be one of the killers, a chemical weapons attack in an international airport, a rare press conference conducted by officials in one of the world's most hermetic regimes and even allegations of an attempted break-in at a morgue holding his body.

Kim Jong-nam – the eldest son of North Korea's Dear Leader – was the globe-trotting princeling and onetime heir apparent to a family dynasty that rules with vicious authority over one of the world's most cloistered nations.

He was a man of airports and casinos, whisky bars and cafés, a voracious reader with a liberal bent who spoke four languages fluently and mixed with billionaires and newly met bar acquaintances alike.

But the trappings of jet-set ease could never erase the essential condition of Mr. Kim's existence: that he spent much of his life trying to escape his past, until one day assassins caught up with him at the AirAsia check-in counter at Kuala Lumpur's discount carrier terminal.

Killed by a deadly nerve agent smeared onto his face in an attack captured by CCTV cameras and broadcast to a world mystified by the strangeness of it all, his death set in motion events that will likely further isolate North Korea. In the days that followed, Pyongyang has traded recriminations with Malaysia, a country with whom it has enjoyed good relations in recent years.

The regime's best friend, too, seems to have turned. Already under pressure from Mr. Trump to force North Korea to give up its nuclear ambitions, China has now pledged to block coal imports from North Korea for the remainder of the year.

The move threatens one of the few remaining major sources of foreign currency for Pyongyang as it pursues a nuclear bomb small enough to be loaded on an intercontinental ballistic missile.

Perhaps the most unlikely character in the tumultuous unfolding has been Mr. Kim himself, a man who by all accounts had little pretension to challenge the power of his half-brother, reigning North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, but instead dedicated his life to books, travel and bonhomie.

To learn more about him, The Globe and Mail travelled to Malaysia and Macau and reached out to acquaintances, friends, former classmates, academics and authors in more than a dozen nations.

Although Mr. Kim rejected the notion that he lived in exile, it is a measure of his nomadic existence that he touched so many places – and a measure of his desire to keep silent his private affairs that few knew much about him. Some close friends, too, worry there is danger in being publicly associated with someone who appears to have been hunted down by trained government killers.

But the portrait that emerges is of a man utterly unlike the dynasty into which he was born or the father who imprisoned, tortured and killed vast numbers of his own people.

Dressed in jeans and blue suede loafers, Kim Jong Nam, the eldest son of then North Korean leader Kim Jong Il, waves after his first-ever interview with South Korean media in Macau.

Shin in-seop/joongang ilbo via AP, File

On the week he died, friends had invited Mr. Kim to a dinner in Macau, where he lived a surprisingly open life, a regular at parties and banquets occasionally spotted in some of the region's many casinos. The friends wanted his support for a charity event to raise money for underprivileged children. Mr Kim had money and a flair for conversation.

"He seemed to have a very kind heart," said Real Hryhirchuk, an Alberta man who has lived in Macau for more than a decade, where he works for an international school with a Canadian curriculum.

He first met Mr. Kim last year at a birthday party being held for a mutual friend. The two struck up a conversation over red wine. Soon the talk had shifted to the U.S. election campaign that was under way at the time."He felt the same way as everyone else, that Trump was crazy," Mr. Hryhirchuk said. He was "just a totally typical, normal guy." They took selfies together, and "he invited us out for dinner to meet with him."

A few months later, Mr. Hryhirchuk found himself at a small Macau sushi restaurant, where a pair of Japanese chefs turn white radish into flowers and deftly slice grouper, cuttlefish, tuna and salmon into plates of nigiri sushi. The restaurant, opened by Mr. Kim and a business partner eight months ago, serves fish flown in from Japan and Australia.

Although it is open to the public – the English-speaking chef demurs when asked about Mr. Kim – the restaurant seemed less a business venture, than a place to have a good time. "I think it was sort of more for hosting friends," Mr. Hryhirchuk said.

"He felt a compassion for people. And obviously that ran into conflict with what his brother's style is," Mr. Hryhirchuk said. "I think he wanted a better future for the North Korean people, which ultimately led to his demise."

North Korean leader Kim Jong-il, front left, poses with his first-born son Kim Jong Nam, front right, and his relatives in Pyongyang in Aug. 19, 1981.

The Associated Press

Born in 1971 in Pyongyang, Mr. Kim was, from the outset, an uncomfortable fit in his own family. His mother, an actress, had been previously married and his father, who also had another wife, sought to hide the birth to avoid raising the ire of his father. Mr. Kim was hidden in a mansion in Pyongyang, where his isolation was nearly complete, living with two cousins, one of whom would go on to write a detailed account of their childhood. He was home-schooled by his aunt and largely barred from leaving the compound, which was staffed by 100 servants, 500 bodyguards and eight cooks, as author Bradley Martin wrote in Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader.

What Mr. Kim lacked in freedom, his family made up for in material extravagance. His father dedicated a special team to the procurement of birthday gifts, among them diamond-encrusted watches and toy guns that were kept in a 10,000-square-foot play room, according to Michael Breen's biography of Kim Jong-il.

Once, when a dentist informed his cousin that there was not enough gold to make a proper filling, Mr. Kim pulled a 10-kilogram gold bar out of his own safe and suggested chipping off a chunk. Another time, he refused to visit the dentist himself unless he was given a Cadillac. He got the car, painted dark blue.

His relationship with his father was good, at first. Mr. Kim was, to those who knew him as a young man, the heir apparent and loved as such.

"When he was a kid, his father said to him: 'I will give you Korea. You will be the master of Korea,'" said Pascal Dayez-Burgeon, a former French diplomat in Seoul who studies North Korea.

Kim Jong-il visited his eldest son often. To ward off the boredom of his isolation and to give him the best possible education, his father let him go abroad.

Mr. Kim did not always find foreign lands to his taste: He once left a school in Moscow because the toilets "disgusted him," said Nicolas Levi, a scholar in the Polish Academy of Sciences who studies North Korea's elites.

But as Mr. Kim spent more time outside North Korea, eventually attending a prestigious private school in Switzerland, his relationship with his home country began to change. In the early 1990s, he accompanied his father on a tour of inspection at home. Rather than luxuriate in the grovelling attention accorded a divine leader, he was struck by how badly the hinterlands of North Korea lagged behind the European centres he had grown accustomed to.

It bore little in common with the paradise depicted by the country's propaganda machine.

"This was something that led to a difference of views with his father," and a falling out, said Yoji Gomi, a Japanese journalist who spoke with Mr. Kim numerous times over seven years, and wrote a book about it.

Mr. Kim became a disenfranchised scion with a power no one could question because of his lineage, a combustible mix in a twentysomething with a taste for booze and women. Even as he started to work for the regime, with a formal party role linked to his interest in computers, Mr. Kim chafed under the strictures placed on him by his father in a country very different from Europe. He "started to lead a very wild life," Mr. Gomi said. He marched around Pyongyang in military garb emblazoned with four stars that would suggest a top military rank, Mr. Martin wrote.

Once, he got drunk and, after discovering a taxi in his parking spot, shot up the lobby of the city's Koryo Hotel. Another time, he opened fire in a night club.

"It forced him to leave the country," Mr. Gomi said. In 1995, the year his first son was born, Mr. Kim decamped to Beijing, where he had a villa on the outskirts of town, and used the airport as his launchpad for travel.

He "was a manager of slush funds for Kim Jong-il," said Mr. Levi, and did business with Japanese and German IT companies. "He was considered an intermediary. Therefore, he travelled all over the world."

That included frequent stops in Moscow to see his mother, who had moved to Russia and was receiving treatment for an array of psychological and physical ailments. It was there that Lee Sin Uck met the young man who wore the style of cheap Italian leather jacket popular at the time. Mr. Lee, a South Korean, was studying in Moscow and had a job tutoring someone at a building next door when he ran into Mr. Kim, whom he first thought was Russian-Korean.

Instead, he found himself speaking to a man born in Pyongyang with a reputation for carousing and womanizing, but also possessed of a sharp mind and an intense curiosity about what lay on the other side of the demilitarized zone. At their first meeting, Mr. Kim asked, "All South Koreans are well off, right?" and said he particularly wanted to visit Gangnam, the posh district in Seoul.

After that, the two engaged in long conversations whenever they saw each other. "We would talk on the street. He seemed to be the kind of person who gets lonely easily," said Mr. Lee, who now teaches Russian politics at Dong-A University in the South Korean city of Busan. Mr. Kim had "a great personality, like a rustic country youth."

The two first met in 1999, when Mr. Kim remained the world's best guess at the next in line to North Korea's highest seat of power. But he was surprisingly open, discussing his mother's health and his uneasy relationship with his father. He "had complaints about his father interfering in his life," Mr. Lee recalled. Those complaints grew particularly acute in their last meeting, in the fall of 2001. "He was upset about it. It was one of the reasons why he had come to his mother."

By that time, Mr. Kim had reason to be upset. He had just endured his first major brush with the global spotlight, when Japanese customs officials deported him for trying to enter the country on a fake Dominican passport. Mr. Kim, who was travelling with two women and a four-year-old boy said he wanted to go to Disneyland.

Mr. Levi disputes that, saying "in reality, he was supposed to arrange some deals with Japanese companies." And it was, in any case, at the time common for North Koreans to travel on falsified passports from other countries.

But the incident, which humiliated North Korea, was widely seen as contributing to the distance between Mr. Kim and his father, a relationship that was already strained. Rather than fly back for meetings in Pyongyang, Mr. Kim would often dispatch his wife to attend in his stead, he told Mr. Gomi.

And eventually, he moved even farther away from home, to a tiny speck of land on China's southern flank.

A flower show attended by upward of 700,000 celebrated the 75th anniversary of the birth of the late Kim Jong-Il, North Korea’s Dear Leader, in Pyongyang earlier this month.

ED JONES/AFP/Getty Images

The flaming lotus design of the Grand Lisboa Casino rises to an enormous architectural homage to a Fabergé egg. Inside, the lobby holds a museum's worth of treasures, including a golden clock that once kept time in the palace of the Chinese emperor and an intricately detailed carving of the Great Wall that took 10 craftsmen six years to etch out of mammoth tusk.

It is a monument to the excess of Macau, a gambling centre flooded with several times more gambling dollars each year than Las Vegas, a crossroads for betters, shoppers and, for many decades, a thriving underworld that secreted goods and money across borders.

It is a place so artificial that even most of its land is manufactured, built out of the sea to make space for more casinos. But, for years, it was a place where, amid the glitz and the outsized personalities, Kim Jong-nam could find a sense of normalcy.

He owed part of that to the modern King of Macau, Stanley Ho, the billionaire best known for the decades when he held a monopoly on gambling in Macau. But Mr. Ho, too, had long made Macau a safe harbour for North Korea, and grew personally invested in keeping the Kims happy.

Before he cornered the market on casinos, Mr. Ho built his early wealth by smuggling goods to China, and is believed to have extended his reach to its close ally, North Korea. In 1999, Mr. Ho opened a small casino in Pyongyang; he even served as a spokesman for the regime. In 2003, he even made public an offer, on behalf of Pyongyang, to give asylum to Saddam Hussein, then on the run from U.S. forces. North Korea, he said at the time, was "willing to give Saddam Hussein and his family a mountain."

Mr. Ho was far from the only Macanese ready to look beyond Pyongyang's pariah status. For years, the region's marble-floored luxury shops welcomed North Korea's small army of dedicated gift-buyers, who scoured the world for cars, watches and gold-plated firearms to buy loyalty among cadres. Macau banks kept safe vast quantities of North Korean cash, the proceeds of the country's illicit trade in weapons, cigarettes and counterfeit pharmaceuticals.

In 2005, when the U.S. Treasury Department accused Macau's Banco Delta Asia of being a "willing pawn" in the caching and moving of North Korean money, it alleged that the bank had accepted deposits worth more than $50-million (U.S.) from a single entity linked to North Korea. (Delta Asia chairman Stanley Au declined an interview request.)

Mr. Kim told friends he made investments and assembled deals. He had recently attempted to help a Chinese hotel magnate assemble a multimillion-dollar wine collection, said a long-time friend of his.

"That was, from what I understand, his business – being something of a consultant for Asians wanting to come to Europe, putting the two together," the friend said.

"He told me he never took money from his father since he left. I don't know if that's true or not."

But in Macau, he was living in a place that money from his father's regime did touch.

"It's so easy to move money in Macau. There's no place like it for making secret deals," a former senior North Korean official told Japanese broadcaster NHK in a 2015 documentary, in which he pointed out some of the buildings where the country's operatives worked and hid gold bullion.

Mr. Ho, meanwhile, appears to have seen value in accommodating Mr. Kim. The billionaire owns the Grand Lapa hotel, an old-world residence that was long the most opulent in Macau, its rooms graced by heads of state. For years, Mr. Kim lived there, too, say long-time local casino executives, who suspect he stayed for free as a guest of Mr. Ho.

Mr. Kim was seen as the "the potential future leader," said one executive with close ties to the city's casino elite.

"Because of his status, he should have a lot of local friends who would be more than happy to pay for the bills," the person said.

Macau held other advantages for Mr. Kim, too.

China's influence gave it a protected air, a place where North Korea would be unlikely to meddle for fear of angering Beijing. Mr. Kim held value as a potential China-friendly leader that could one day claim the throne in Pyongyang. But Macau's distance from Beijing allowed Mr. Kim to escape the people that constantly surrounded him in China – watching him or protecting him, he never knew, he told Mr. Gomi – while enjoying the pleasures of a place devoted to keeping people happy.

Here, in a former Portuguese colony that retains a European and democratic sensibility, he could also lead an approximation of normal life. His children attended local schools – his daughter remains enrolled in Macau Anglican College, although she has not been seen since her father's death – and the family lived for a time in a tony seaside community home to business and political elites in Coloane. Inside the compound, a driver points to a villa emblazoned with a small golden sun that looks out over the water. Mr. Kim's black luxury car was here as recently as December, the driver says.

But today ,the curtains are drawn and the door locked, a reminder that in recent years, Mr. Kim's sunny days in Macau hid a darker reality. His life was growing dangerous.

On the Feast floor of Kuala Lumpur's Starhill Gallery mall, vermilion escalators resemble a red carpet rising toward pillared balconies that look down on a cluster of restaurants that serve cuisine from around the world. The Prime Minister and sultans alike occasionally pass through here, in the heart of one of Malaysia's most posh shopping centres.

They come here not just for the food. They come for the peace of mind. That's what brought Mr. Kim here, too, says Alex Hwang, who owns the Koryo-Won restaurant, a place Mr. Kim visited more than a half-dozen times.

"This place is No. 1in Malaysia for security," Mr. Hwang said. Even so, Mr. Kim was usually accompanied by a pair of women Mr. Hwang believes were bodyguards, and often wore a cap pulled down over his face to hide his features. As he ate, he kept a wary look at his surroundings.

"It's a terrible life, isn't it?" Mr. Hwang said. "Dangers everywhere, and he doesn't know when he will be killed."

Mr. Kim had long ago concluded that North Korea needed to follow a radically different path, opposing the hereditary transfer of power to the third generation of Kims and, in occasional interviews, calling for North Korea to adopt Chinese-style reforms. Without such change, the country would risk failure, he warned.

"He was very lucid about the regime. He thought the old ways were over," said the long-time friend. "He foresaw problems. And he didn't want to be part of it."

Such thinking made it unlikely he would become North Korea's next leader. Thoughtful and social, he did not share the icy ruthlessness that had brought his father to power, and became a central element of his rule.

But in 2011 when Kim Jong-un, a half-brother he never met, was crowned the third-generation ruler of North Korea, Mr. Kim's thoughts toward the regime also placed a target on his back.

Overnight, Mr. Kim "said that the feeling around him became even more severe," said Mr. Gomi. "He felt he was being suspected of perhaps harbouring ambitions to eventually take over the government."

Mr. Gomi had spoken at length with Mr. Kim, sitting down for seven hours of interviews, and exchanging 150 e-mails. He was struck by Mr. Kim's appetites – "he drank whisky at a very fast pace, so fast I was concerned about his health" – and his intelligence. He demonstrated a deep, insider's knowledge of what was happening inside North Korea, and when Mr. Gomi sent him books about his home country, "he would always immediately say, 'I have already read it.' The impression I got was this was a man who was very well-read."

But when Mr. Gomi said he intended to publish their conversations in a book, Mr. Kim immediately cut off all communication. That same year, he survived an assassination attempt and, according to South Korean intelligence, wrote a plaintive letter to his half-brother, begging for mercy. One defector told Mr. Gomi that, inside North Korea, rumours had begun to spread that Mr. Kim had been critical of the regime, "and that this could be the cause for change."

However, Mr. Gomi said, "I do not really know whether that had led to an anti-establishment movement in North Korea. Most likely that was not the case."

In Macau, though, Mr. Kim told his friends he no longer felt safe.

"'My brother is trying to kill me,'" he said to Jay Chun, a local business leader. "I thought it was a joke," Mr. Chun said, in an interview with Macau Asia Satellite Television. "I didn't expect it to really happen."

AirAsia flight 8320 leaves Kuala Lumpur daily at 10:50 a.m., an Airbus-330 jet filled with young couples, middle-aged men and an occasional monk bound forMacau and its oceans of slot machines and playing tables. Hours before the flight, they gather inside the gleaming interior of the city's discount carrier terminal, where the AirAsia check-in counter sits surrounded by shops and restaurants selling sweet coffee and salted fish fried rice.

Mr. Kim, too, knew this place well. AirAsia Flight 8320 is the most convenient direct connection between Macau and Kuala Lumpur, and he came to Malaysia often. If Macau is where North Korea moves money, Malaysia is one of the places the country earns it.

Attracted in part by a border policy that allows them 30-day entry without a visa using passports that in many other countries are not welcome, hundreds of North Korean businessmen now work in the city, in fields as diverse as computer animation, construction and seafood exports. A new report to the United Nations identifies Malaysia and China as primary locations for North Korean firms used to skirt sanctions and bring money to the regime, including one Malaysian outfit that appears to be a front for a company run by the country's intelligence service, Agence France Presse reported this week.

So there was nothing unusual about a North Korean man – even the son of a dictator – striding toward the check-in counters, in a suit and open-collared shirt and towing a rolling suitcase.

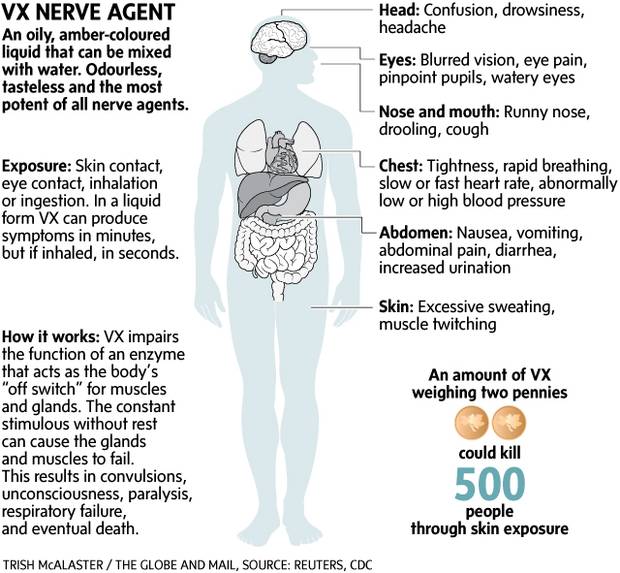

What happened next has become daily fodder for newscasts and newspaper front pages: two women approached him and smeared his face with something authorities now say was VX nerve agent, a substance so deadly it is classified as a weapon of mass destruction, potent enough that a single drop can kill a human.

It was an extraordinarily brazen act, bringing a chemical weapon into an international airport – and one that stands to worsen the economic and political plight of a country already under severe sanctions. In the days that followed, China has moved to tighten its border against coal imports from North Korea; on Friday, Malaysia's deputy prime minister ordered a review of the country's diplomatic ties with Pyongyang.

Booting the North Korean ambassador from Kuala Lumpur "is becoming a real possibility," said Shahriman Lockman, senior analyst at Malaysia's Institute of Strategic and International Studies. "I strongly suspect that government officials are looking into enforcing international sanctions with greater vigour."

Mr. Kim's death, however, fits with a pattern of pettiness and brutal reprisal that are among the hallmarks of the Kim dynasty. Numerous family members have been killed, including by reigning leader Kim Jong-un, who executed his uncle, Jang Song-thaek, a man who had frequently met with Kim Jong-nam over the years.

As a half-brother, Mr. Kim also represented a so-called "side branch" to a family tree that the Kim dynasty has over the decades often violently pruned. Kim Jong-il once pulled his daughter from school rather than have her attend the same institution as the nephew of another of his father's wives. A few years later, Kim Jong-il had the entire school blown up by a demolition squad, according to an account published by Kim Hyun-sik, who once taught the former leader.

"By demolishing the school, Kim Jong-il was effectively declaring that he, and only he, was the rightful successor," Kim Hyun-sik wrote in 2009.

For Kim Jong-nam's friends, his death has left a feeling of disgust, as they recall a man who had sought – and, it appears, ultimately failed – to distance himself from the family he was born into.

"He described serious depression he had, living in a situation of plenty where people around him were struggling. He couldn't deal with it. And he had to leave. He didn't want to stay in that. He didn't agree with what was happening," said Anthony Sahakian, a former classmate living in Geneva who saw Mr. Kim frequently in the past two years.

"I just think he wanted to live a peaceful life with his family."

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL