Streaming song and dance

Six years is a lot of time in the Internet age. Back in 2009, when people wanted to hear new music, they usually turned to download retailers such as Apple’s iTunes store. Streaming music services were just niche products enjoyed by the most hard-core of music fans. And despite releasing a best-selling album, a young country artist named Taylor Swift’s biggest news that year was getting interrupted on stage by Kanye West.

Today, Ms. Swift is one of the world’s biggest pop stars, and she has seized full control not just of her own narrative, but the whole music industry’s. All-access streaming services have become a dominating force in music consumption, and Ms. Swift has become their chief critic, regularly withholding her smash-hit albums from major players and speaking out against their poorly paying business models.

Two weeks ago, world-leading music retailer Apple announced it was entering the streaming world with Apple Music, a $10-(U.S.)-a-month service with a three-month free trial. News quickly followed that no royalties would be paid to rightsholders during the revenue-free trial period. This, to Ms. Swift, was a merciless move for the tech giant, which has at least $170-billion in cash reserves; she took to her blog on Sunday to call it “shocking, disappointing and completely unlike this historically progressive and generous company.”

Just hours later, Apple relented, with software head Eddy Cue posting on Twitter that the company would pay artists during the trial period.

#AppleMusic will pay artist for streaming, even during customer’s free trial period

— Eddy Cue (@cue) June 22, 2015Streaming, the all-access, flat-fee model of music consumption, is widely considered among music experts and industry optimists to be the next great hope. It’s been around for years – Apple, as usual, is riding the trend’s coattails – but downloads are now declining as maturing streaming services, including Spotify, Rdio, and Tidal, sign up users by the millions.

But Ms. Swift’s missive is just the latest sign that the nascent business model is on shaky ground. Artists don’t feel they get a fair cut, most consumers think it’s too expensive and legacy industry players are effectively praying for profits. If streaming is the future of music, the road ahead will be a lot rougher than the CD-fuelled high-margin easy streets of the nineties.

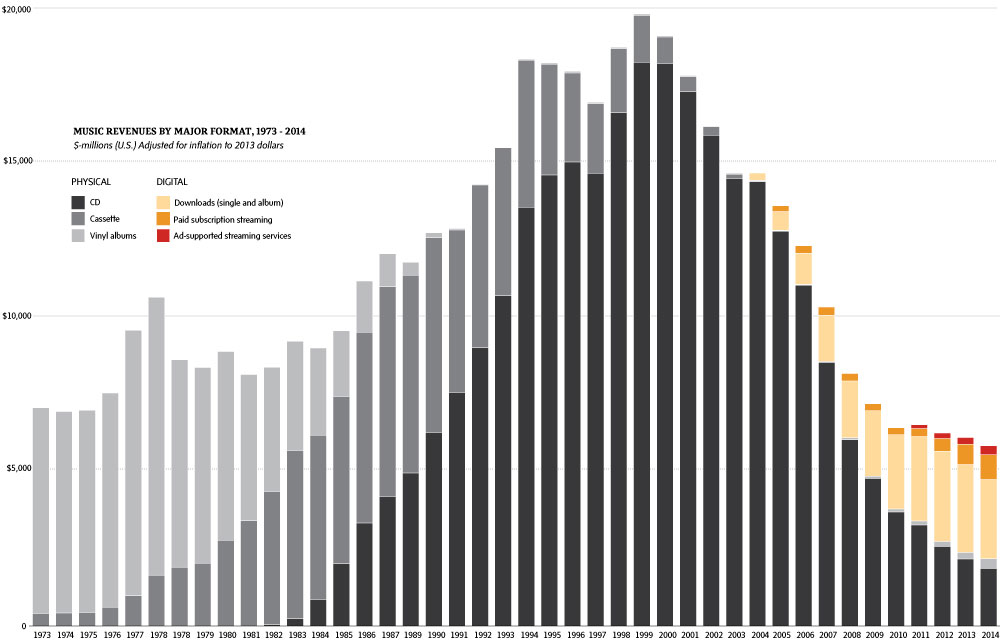

It used to be easy for the music industry to find money-making ways to solve its problems. When piracy emerged in the Internet’s early days, regulated download retailers such as iTunes were considered a salvation. But like CDs, cassettes, and vinyl before them, downloads are purchases that could be owned and used ad infinitum.

Streaming represents a far greater shift in technology and behaviour. To a growing number of consumers, music is no longer a product – “it’s a service industry,” says Catherine Moore, a Canadian-raised music-business professor at New York University. For about $10 a month, usually, consumers can use Spotify, Rdio, and starting June 30, Apple Music, to listen to catalogues of 20 to 35 million songs as often as they want.

Some services have free tiers that force users to hear ads, which are growing at a similar pace, and there are playlist-based services that are cheap or free, too – though they deliver even less money, generally, to rightsholders. Apple Music, is an amalgam of both these models: users will be able to stream at will from Apple’s vast catalogue or enjoy preprogrammed stations, including Beats1, helmed by former BBC tastemaker Zane Lowe.

Revenue from subscription services grew 39 per cent worldwide last year, according to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, but the broad adoption only served to offset declining download numbers; the $15-billion (U.S.) industry saw no growth in 2014. On a conference call with reporters in April, Sony Music Entertainment’s global chief executive officer Edgar Berger told reporters that scaled-up streaming adoption is labels’ bet on bringing money back. “The irony really is,” he said, “that digital disruption through the rise of subscription services will transform the once-volatile music industry into a stable business.”

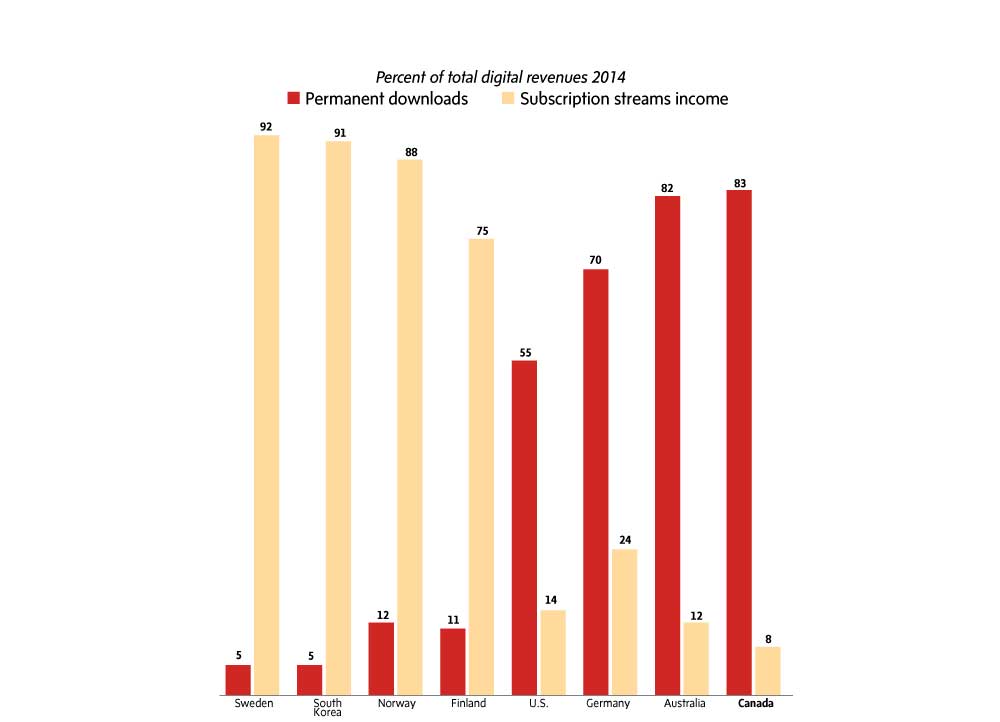

Apple, which has millions of credit card numbers in iTunes ready to convert to streaming with a single click, is poised to boost streaming adoption. Amy Terrill, Music Canada‘s vice-president of public affairs, says it “bodes well for Canada” that Apple is bringing mainstream attention to streaming. It’s one of the last major music markets to embrace the technology, with only 8 per cent of digital revenue in 2014 coming from subscription streams, versus 23 per cent globally, says IFPI data; total music-industry revenue fell 11 per cent here last year.

According to data provided to The Globe from Nielsen Music, this might be hard to pull off. Canadian music listeners say they’re willing to pay for unlimited streaming, but only $6.20 a month; they’d go up to $7.80, but only for high-fidelity audio. In reality, those services usually cost $10 and $20, respectively. With streaming companies struggling to profit, the price is tough to pare down. Rdio recently announced a $3.99 monthly tier, but it only allows 25 new songs to be streamed a day.

With Apple entering the ring, “competition will intensify,” says Rdio CEO Anthony Bay. “Over all, it’s a net positive, because awareness will go up. … It becomes an opportunity for everyone to present their value proposition.”

Artists and songwriters, meanwhile, are bracing for a change in lifestyle. Zoe Keating, a California-based Canadian cellist, calls her home “the house that iTunes built,” in homage to the mortgage-paying income she gets from the retailer, but is worried the shift to streaming will leave her searching for other income streams.

Drinking from this bottomless well is a great thing for consumers, but the flat fee means suppliers – musicians – generally make less money. There’s no limit to the number of albums you can sell, but when everyone streams at at a fixed price, the playing field gets skewed. Ms. Keating has made a-third-of-a-cent per stream on average so far in 2015; 1.5 million streams has yielded less than $5,000.

The problem comes down to proportion. The vast majority of money from pooled subscription revenue goes to high-rotation hit makers like Katy Perry and Drake, leaving the rest to be divided among millions of other artists. “People are streaming more, but I’m making less,” Ms. Keating says.

When it was first revealed that Apple Music wouldn’t pay artists during its trial period, indie labels worldwide shouted their frustrations. “I can’t think of any other industry that bases its business model on not paying their suppliers,” says Canadian Independent Music Association president Stuart Johnston. He’s happy Ms. Swift threw her voice into the fray, but says paying artists “should have been a decision they made right from the start.” (Apple declined to comment for this story.)

Leaked contracts between labels and streaming services show that artists’ interests aren’t exactly top-of-mind as the industry adjusts to the new normal. The Verge obtained an early contract between Sony and Spotify that outlined millions of dollars in advances to the label with no clear indication of how much flowed to musicians. Many artist contracts were drawn up before streaming services matured, so while the details may be legally sound, they’re not necessarily fair for talent.

Safwan Javed, an music-focused lawyer and drummer for the band Wide Mouth Mason, says it’s crucial that contracts become more fair and transparent to all players. “It goes without saying that you want an ethical model to ensure everyone in the value chain is getting their fair share,” he says. “So far, the streaming model has left a lot to be desired.”

With streaming’s current business model, there will most likely be less money in the pot for the creative end of the supply chain. This, Mr. Javed says, will inevitably trickle back to the consumer. “People who spend all their time honing their craft, that number’s going to shrink, and that means there’ll be less – and less quality – stuff out there.”

Streaming’s arms race

The world’s biggest company is late to the streaming game, and its new service, Apple Music, largely co-opts features available in existing streaming services. But because iTunes is already a destination for millions of consumers – who’ve already handed over their credit card numbers – Apple has the chance to be the world’s streaming leader in a matter of months.

YouTube is the Internet’s premier destination for music; owner Google announced the “Music Key” paid service last year that strips videos of pre-roll ads, enabling nuisance-free listening akin to audio-focused streaming services. Google also recently acquired the free playlist service Songza, and offers free and paid tiers of Google Play Music, an all-you-can-stream audio subscription service.

The world’s biggest streaming service has 75 million active users, 20 million of whom pay monthly subscriptions. In May, Spotify announced video content and customizable features to keep users in the app for their whole day. Just after Apple threw its hat into the streaming ring, the Wall Street Journal reported that Spotify had just closed a $500-million (U.S.) funding round, valuing it at $8.5-billion and giving it a huge war chest to fight the tech giant.

Available in more than 180 countries – versus Apple Music’s 100 and Spotify’s 58 – Deezer is perhaps the most widely available subscription streaming service out there. But at six million paid users, it’s a distant second to Spotify in a market that Apple is only making more competitive.

While Spotify waited until last fall to enter Canada, Rdio launched here in 2010, earning the allegiance of hungry Canadian music fans. Its new $3.99 “Rdio Select” tier, letting users stream 25 new songs each day, is geared toward bringing more casual users to the service. It doesn’t reveal user numbers, but even with that tier, it has a lot of catching up to do with Apple and Spotify.

The celebrity-owned high-fidelity service promises to put more money in the hands of musicians while offering exclusive content for paying subscribers. But it’s had trouble attracting users – less than a million – and the high-fidelity option costs $20, double the usual rate for streaming services.