Despite it’s economy of means, Genizot: Repositories of Memory has a density of intellect, gravitas of presentation and intensity of feeling

It takes a bit of effort to locate Genizot: Repositories of Memory at the Royal Ontario Museum. It’s a small, temporary show by Toronto illustrator/painter/writer Bernice Eisenstein, tucked into a third-floor roomette just across from a display of medieval armour and hockey gear, near the entrance to the Weinberg Judaica Collection and Bernard and Sylvia Ostry’s collection of art-deco masterpieces. Even with signs pointing the way, I strode by it twice the other day before finally zeroing in.

In terms of layout and constituent parts, the exhibition is the soul of simplicity: two walls, both painted grey, each hung with five same-sized framed portraits, nine of them in gouache and charcoal, one in pen and ink. In the space between (the walls, that is), Eisenstein has positioned a modest-sized vitrine, its interior an artful clutter of objects, “found” and made. Yet for all this economy of means, Genizot has a density of intellect, gravitas of presentation and intensity of feeling greater than some exhibitions 10 times its size.

The show takes its title from the plural form of the Hebrew word for the temporary spaces, usually in synagogues, in which Jews store worn-out or damaged Hebrew-language books and papers of varying degrees of religious content before their formal burial in a cemetery. (Judaism forbids the discarding or destruction of any writings containing the word of G-d.) Eisenstein, 65, perhaps best known for her 2006 graphic memoir, I Was the Child of Holocaust Survivors (her parents, in fact, met during the liberation of Auschwitz in early 1945), prepared the installation last year while serving as artist-in-residence at the Neuberger Holocaust Education Centre in Toronto.

It’s a decidedly European exhibition in that the portraits, most limned in plangent tones of grey, black and white, their eyes so far away, are of Western and Middle European figures born in the late 19th or early 20th century. They include the photographer David (Chim) Seymour and writers Marcel Proust, Stefan Zweig, Robert Walser and Felix Salten, the last the author of Bambi: A Life in the Woods. Stylistically, Eisenstein works in an expressionistic key that, in terms of antecedents, looks to Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Ben Shahn while echoing contemporaries such as Maira Kalman and Mark Ulriksen.

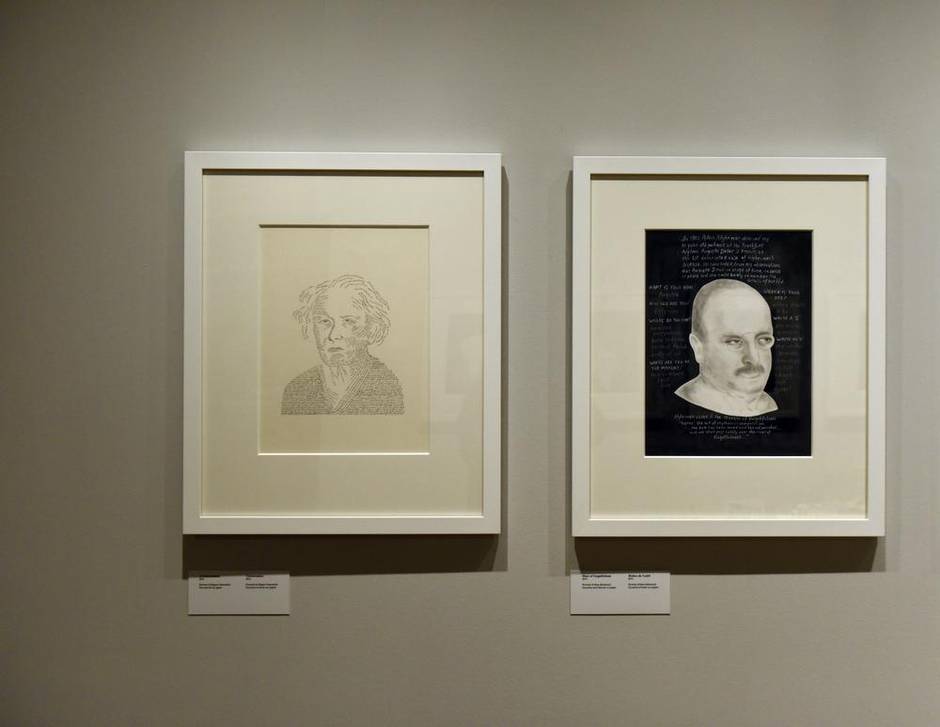

Most, though not all, of Eisenstein’s faces are Jewish. Yet each is linked, by preoccupation or occupation, with a concern for memory – the preservation and transmission of its contents, its slipperiness and fragility, its bittersweetness, its fragmentation, deterioration and loss. So you have the portrait of aviator/author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry positioned alongside that of Léon Werth, the French critic/novelist/essayist, to whom Saint-Exupéry dedicated his most famous work, The Little Prince, in 1943. Similarly, the gouache of Alois Alzheimer, the German-Polish doctor who, in 1901, provided the first description of the disease that bears his name, hangs beside Eisenstein’s portrait of her (still-living) mother, Regina, the face rendered in winding strands of minuscule, inked words and sentences (reads one: “For a while I would visit and we would play cards while she could still remember to hold them”).

All the portraits, in fact, are filled with words: That of Zweig, who fled Nazi Germany in 1934 only to kill himself in exile in 1942, is backgrounded by the names of the artists featured in the infamous “degenerate art” exhibition the Nazis curated in Munich in 1937. Proust’s face is surrounded by a cascade of almost 1,000 words, written right-side up, upside down and sideways, derived from Remembrance of Things Past; Chim’s is flanked by an inventory of the personal effects found at the time of his death in 1956, his suit jacket a weave of the words from the obituary issued by Magnum, the illustrious photo agency he co-founded.

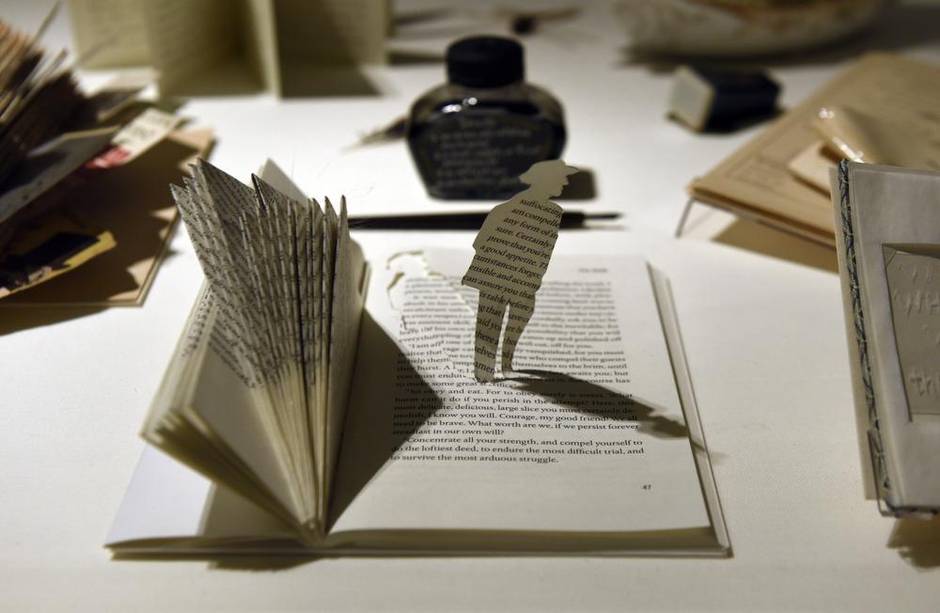

Conversing with the icons on the walls is the vitrine, with its potpourri of small, three-dimensional mnemonics, variously allusive and elusive, evocative and provocative. Among the objects: a feather, an ink bottle with dip-nib pen, a dragonfly, a cockroach, a cheap ceramic of a cherub paddling a vessel with a bird-head prow, a broken eggshell in a nest, a couple of glass lenses, three keys, the wedding certificate of Eisenstein’s parents, a tie clip of (apparently) her father’s. And, of course, befitting Eisenstein’s reverential, readerly sensibility, there are books – a folded copy of Bambi inserted with the miniature covers of titles such as Ulysses, A Farewell to Arms, The War of the Worlds and Theodor Adorno’s Minima Moralia; a copy, also folded, of Walser’s novella The Walk, with its admonition to “concentrate all your strength and compel yourself … to endure the most difficult trial and survive the most arduous struggle,” in addition to an Eisenstein handmade containing mini-portraits of Einstein, Kafka, Camus, Emily Dickinson and Goodnight Moon creator Margaret Wise Brown.

Here, in short, we have a concentrated show, haunted and haunting, requiring the viewer’s concentration and time to excavate its myriad impacts.

Genizot: Repositories of Memory by Bernice Eisenstein is installed at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, through Feb. 8 (rom.ca).