The best art collectors do a lot of looking. Hard looking. Which is just what Torontonians Ann and Harry Malcolmson did for several years before purchasing, in early 1988, the first photograph in what would eventually become a superb, centuries-spanning collection of almost 300 historic/archival photographic images of the predigital era.

That first purchase, from pioneering Toronto photography dealer Jane Corkin, was a doozy: a 1907 photogravure on vellum of Alfred Stieglitz’s The Steerage, “likely the most iconic single picture in photographic history,” in Harry Malcolmson’s informed estimation. You can see it for yourself right now at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, which until Sept. 7 is exhibiting, in its spacious, high-ceilinged European Galleries, some 85 or so highlights from the more-or-less complete collection acquired from the Malcolmsons last December.

Recently, The Globe and Mail asked husband and wife, married since 1958 (he’s a former lawyer, art critic and IMF/World Bank consultant, she a former social worker) to visit the AGO to pick, and comment on, a handful of personal favourites from among the highlights presented by the gallery’s associate curator of photography, Sophie Hackett.

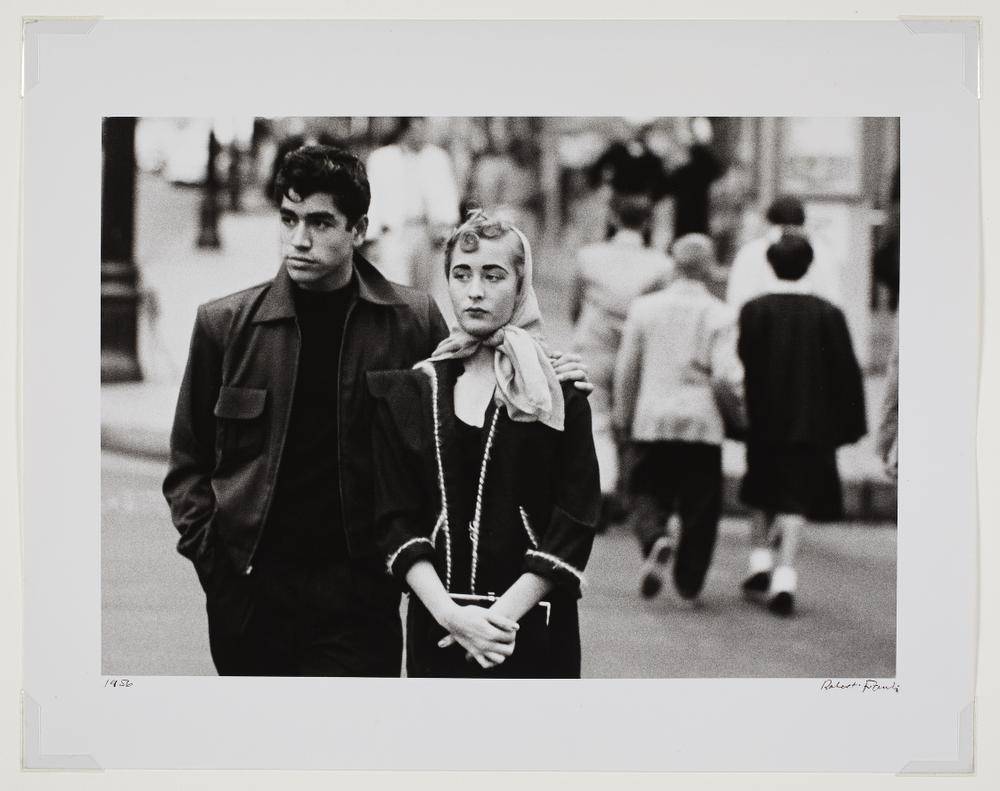

Chattanooga, Tennessee

by Robert Frank (1956, printed 1970s), gelatin silver print

This image is included in The Americans, published in 1958 and probably the most influential book in postwar North American photography. The Swiss-born Frank criss-crossed the United States between 1955 and 1957, eventually shooting more than 25,000 pictures. The Malcolmson Collection includes works by 110 photographers but Frank is one of about a half-dozen artists the couple collected in some depth. The others include Manuel Alvarez Bravo, André Kertész, Man Ray and Bill Brandt.

Ann Malcolmson: This used to be in our bedroom. I looked at it a lot when I was sick one time. It was just as Obama was running to be the Democratic presidential candidate [2012].… This somehow echoed some of the same feelings of the time, of people looking forward, looking into the future but with quite a bit of hesitation and anxiety. It’s the look in their eyes.

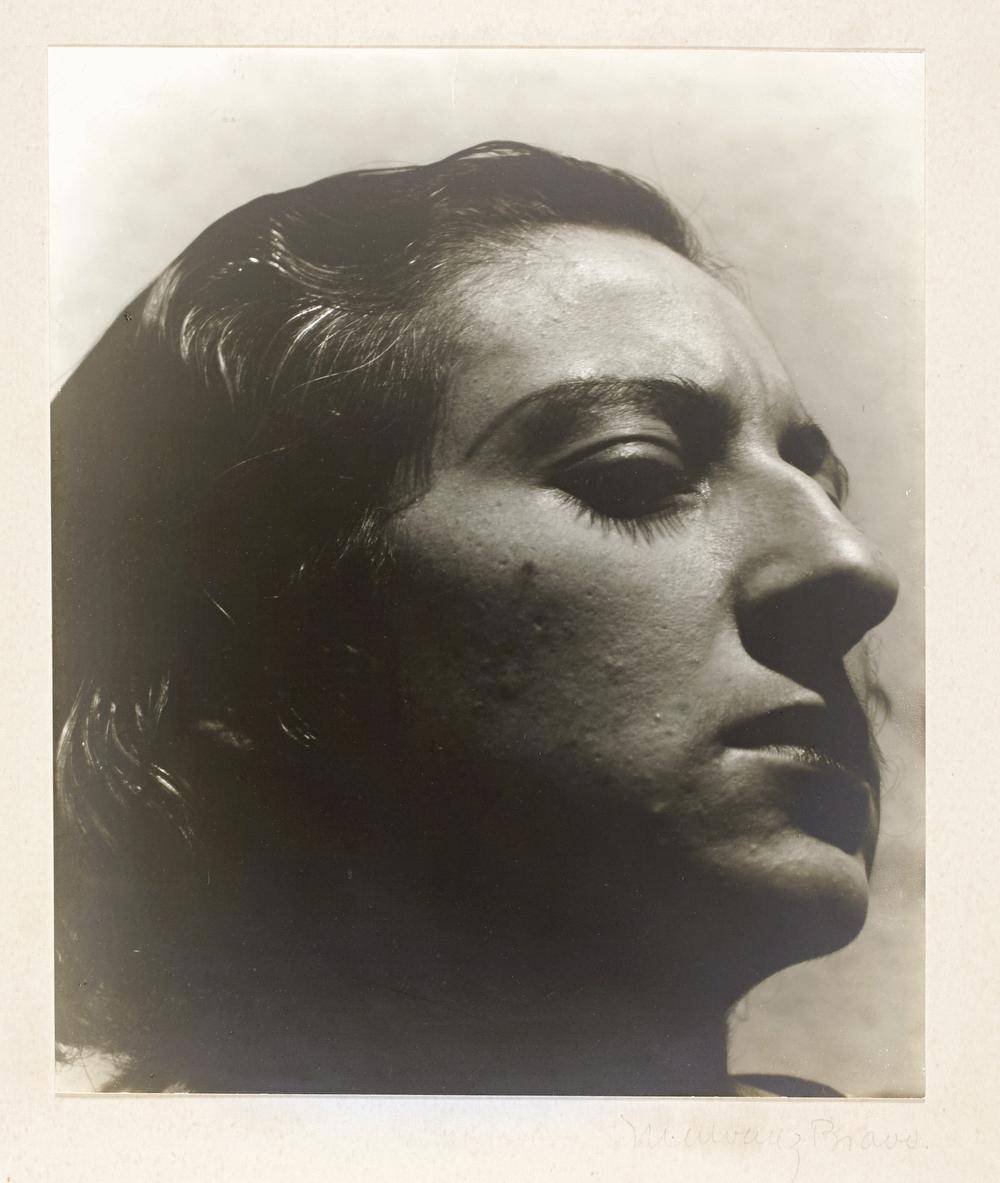

Retrato de mujer [Portrait of woman]

by Manuel Alvarez Bravo (printed 1932), gelatin silver print

Harry Malcolmson: This is a picture of Bravo’s first wife, Lola, also a photographer, whom he met in the mid-1920s in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution. What is remarkable about it is that it ended the period where portraits by serious photographers, even in Latin America, were made on the European model, so to speak. He presents Lola in her Mexican-ness. What we see is the Mexican character of purposefulness, indomitability, resilience. It’s almost like a bronze sculpture in its coloration. The way the head fills the space, the unconventional cropping, it makes you think of a sculpture on a pedestal.

Château of Princess Mathilde, Enghien [France]

by Édouard-Denis Baldus, 1854-1855, salted paper print made from wax-paper negative

Mathilde Bonaparte (1820-1904) was the niece of Napoleon I and first cousin of Napoleon III. She entertained prominent men of arts and letters in this home just north of Paris. Other vintage prints of this image can be found in the collections of the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Ann Malcolmson: It has a mystery to it, something that’s almost unreal. It isn’t just a picture of a landscape but a picture with a lot of questions, emotions and subtleties to it. Baldus was asked by Napoleon III to do a portfolio that he could give to Queen Victoria. She was going to be taking the train down to Paris so he wanted the pictures to be of things that she would see. This was in the summer of 1855 but the wintry look and the shuttered windows indicate Baldus likely took it a year earlier. I take great pleasure in the texture, the feel, of this paper print and I love the richness of its tones.

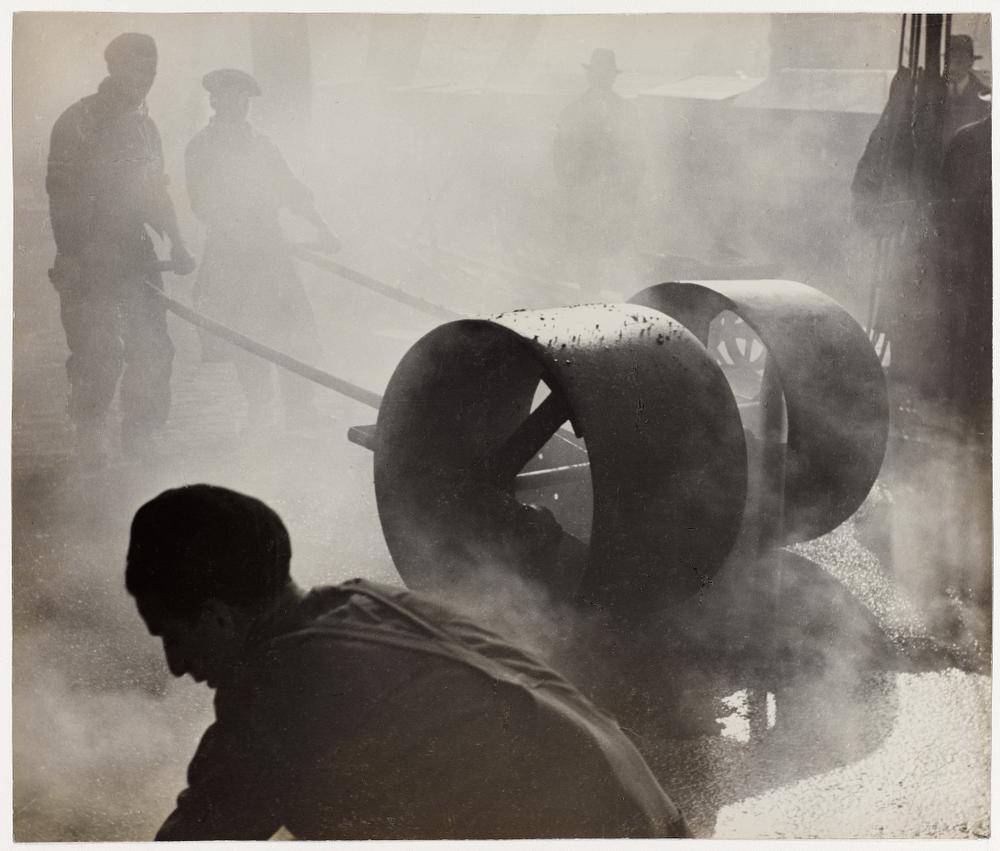

Street Work

by André Kertész, 1929 gelatin silver print

Harry Malcolmson: A very, very unconventional Kertész. His heartland was observation, sophisticated documentation, a realization of the world as it rather literally is. This work isn’t so much a documentation as a representation of an idea of the character of an activity. It’s presented in a non-literal way, a kind of ethereal, moody presentation.… It’s very painterly in that the silhouetted figure in the foreground seems almost designed as a means to present the depth of the work. Also uncharacteristic is that none of the figures have any personal individuality. There have no features and the emphasis is not on any human being but rather on the asphalt drums. What we’ve found among people who really know their Kertész is they either like it or don’t like it. We’ve had estimates of its value and of the entire collection, it’s the one photograph where the variation in monetary terms has been unbelievably variable.

The Great Wave, Sète [France]

by Gustave le Gray, 1857 albumen print from two collodion-on-glass negatives

Harry Malcolmson: An iconic photograph for a number of reasons, not least because it upset the artists of the day very much in that it intruded on their turf. It wasn’t simple documentation, which back then was regarded as photography’s proper role. Rather, there’s poetry here – about the sea, the force, dynamism and majesty of nature. Also the fact that this image is made from two negatives – the sky is something you’ll see in other le Gray photographs – is a sort of anticipation of digital photography.

Some comments have been edited and condensed.