Sylvie Fortin became director of La Biennale de Montréal the way other people take possession of a house that has just been gutted. She had no staff, no program and no financing she could count on for an event that some doubted would ever happen.

That was in September, 2013. A year later, the biennale has opened its eighth edition with work by 50 artists and collectives from 22 countries, including the likes of Shirin Neshat, Thomas Hirschhorn and Isabelle Hayeur. The pieces, half of which are new creations, will be shown in 22 venues, including some outdoor projection sites visible from the sidewalk. Fortin’s budget has gone from nothing to $3.6-million, more than half of which comes from private sources – an unheard-of amount, especially in Quebec.

On the front of the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (MACM), which co-operated in the merger of its own Québec Triennial with the biennale a few months before Fortin was hired, the exhibition’s googly-eyed logo stares out at Saint Catherine Street as if in amazement that the show is actually going on. Several audio speakers on the pavement relay bits of chatter and song from Polish artist Krzysztof Wodiczko’s projection of homeless people, visible on the upper reaches of Place des Arts’ nearby Théâtre Maisonneuve.

“This needs to be for all of Montreal,” Fortin said in a recent interview. Her primary remit was “to do something that would mobilize the community, and for me that was the most important thing. Because if it were just the museum and the biennale – one plus one equals two – then why bother?”

“Why bother?” had become a question that haunted some previous biennales, before the appointment of well-respected curator Nicole Gingras as executive and artistic director two years ago. But Gingras made a swift, unpeaceful exit just six months later, after a merger engineered by money manager Cédric Bisson and tech entrepreneur Alexandre Taillefer, each a member of the separate boards that had overseen the biennale and triennial.

“There is no room for two small, nichey events, both underfunded and both failing to receive the attention they deserve,” Bisson said when the merger was announced, and the eighth biennale postponed, in April, 2013. Taillefer, who is perhaps best known in Quebec as one of the panelists on the Radio-Canada version of Dragons’ Den, told La Presse that, within 10 years, the new entity would be one of the “20 or 25 biennales that you absolutely have to see worldwide.”

The former biennale “felt like an organization that had run out of breath,” Fortin said, while acknowledging that for much of its life, she had been out of town or out of the country, most notably for a seven-year stint as editor-in-chief of Atlanta-based Art Papers. There, in the land of thin public subsidies, she learned how “not to worry about talking about money and asking for help.” She also built a network of international connections that served her well when trying to conjure a new organization and large-scale art event in 13 months. But her first task on returning to Montreal last year was to persuade government agencies and the local community that the new independent biennale had a future.

In a way, “the future” had already arrived, as it was the theme chosen for the event postponed after Gingras’s departure. The idea and its co-curators – Gregory Burke, former director of Toronto’s Power Plant; independent curator Peggy Gale; and Lesley Johnstone and Marc Lanctôt, both curators at MACM – were retained for the current biennale. Ten of the 20 artists they had chosen for the 2013 event were also kept, Fortin said, although with different projects, more in keeping with the new event’s larger scale.

The biennale’s title – L’avenir (looking forward) – is timely, she said, because of what she called a 15-year period of “archival fever in contemporary art. Everything has been about digging in the past, which is very important, but what do you do with it? How do you begin to think about what the next step is? There’s been an unwillingness to dare to think about the future.”

The future has a peculiar resonance in Montreal, where Expo 67’s date-stamped vision of a shiny, engineered Terre des Hommes still lingers in public consciousness – and on the skyline, in Buckminster Fuller’s landmark geodesic dome. Burke’s curatorial statement says that several biennale artists focus instead on failed utopias, the end of the modernist adventure, and even “a loss of futurity” – the notion that “we are in an epoch that has gone beyond a point of no return.”

Fortin prefers to think of the event as “a rehearsal space for possible futures” – as well she might, given the recent history of her organization. She said she hasn’t yet given a thought to what the next biennale might bring in 2016. “The main thing is to listen, pay close attention, see what does or doesn’t get understood this time, and work from there.”

Biennale’s must-sees

Illusions & Mirrors, Shirin Neshat

The Iranian-American’s wordless short video installation has a dream-like Gothic air, as a woman (Oscar-winner Natalie Portman) pursues a man – or the idea of one – across a blurry beach and into a grand house where shadows of the past, or actual people, await. The most startling thing about this fine-art installation, however, may be the credit at the end to Dior, patron of the project and – one assumes – of Portman’s clingy black dress. (At theMontreal Museum of Fine Arts)

Preuzmimo Bencic (Take back Bencic), Althea Thauberger

The Vancouver-based video artist persuaded authorities in Rijeka, Croatia, to let her and a few dozen local children take over an abandoned 19th-century factory before its renovation as a cultural centre. The children dance, sing and re-enact the hopes that animated the factory during its life as a communal workplace in postwar Yugoslavia, and the betrayals and disappointments of the Balkans war era. (Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal)

Hexen 2.0, Suzanne Treister

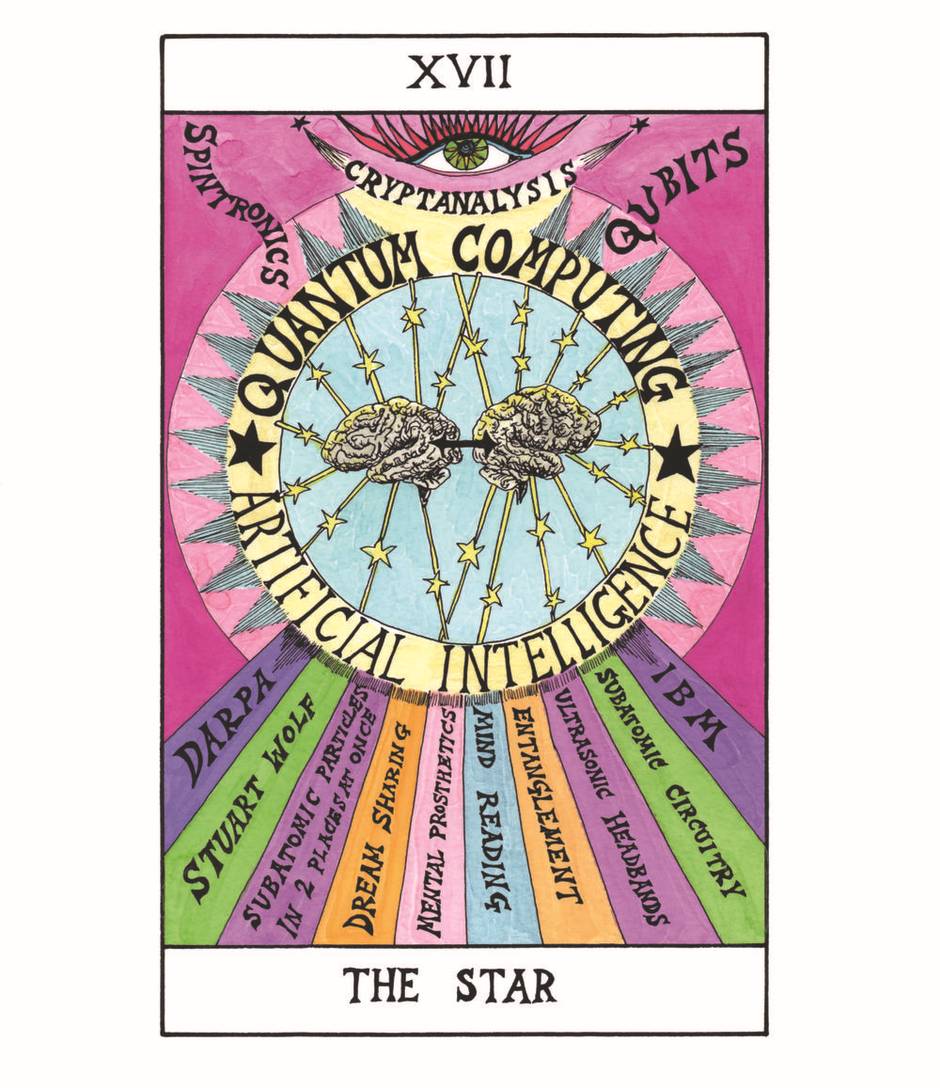

Britain’s Treister renders the networked intellectual prehistory of the wired age through coloured drawings of a tarot deck, tracing influences from Henry David Thoreau to cybernetics guru Norbert Wiener to the “technogaianism” of NASA scientist James Lovelock, as a way to fix the environment through technology. The heavily detailed drawings owe much to the geometries of Masonic symbolism, although the card for William Blake (five of wands) pays tribute to his distinctive organic style. (MACM)

Murs aveugles (Blind walls), Isabelle Hayeur

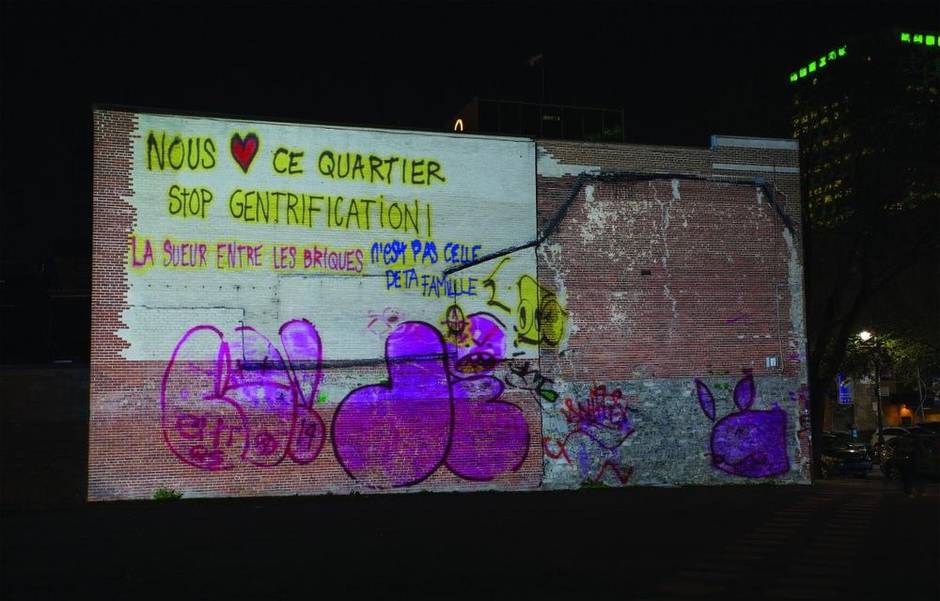

Montrealer Hayeur’s outdoor projection features a series of slogans, graffiti and other graphics related to the Occupy movement that burst forth in the city and around the world in 2011. The bright revolutionary fervour (“the power of the people is stronger than the people in power”) contrasts sharply with the desolation of the empty lot facing the projection surface, a brick wall scarred with the ghosts of vanished buildings. (St-Laurent Métro station)

L’avenir (looking forward), the eighth Biennale de Montréal, continues at various locations around Montreal through Jan. 4, 2015.