Kelvin Harrison Jr. in the film Chevalier, by Canadian director Stephen Williams.Photo Credit: Larry Horricks/Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures / 20th Century Studios

A new movie about Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, details the life of the late 18th-century biracial polymath across music, politics and the aristocratic circles of Paris and London. Directed by Canadian Stephen Williams, Chevalier, which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in September and was released last month, is part of a broader wave of interest in the composer-artist-virtuoso that is inspiring a wholly overdue reckoning within the classical world.

Born in 1745 on the French island of Guadeloupe to a wealthy planter and his enslaved teenage mistress, Bologne arrived in France in 1753 and initially became famous for his swordsmanship. Louis XV recognized Bologne’s immense fencing skills and bestowed the title of Chevalier de Saint-Georges (derived from his father’s noble title), though Bologne was prohibited from acquiring it officially because of his African ancestry.

That was only one instance of the racism Bologne would encounter throughout his short life. The Paris Opera, for instance, would have been under his directorship but for a petition by three company singers, who told Marie Antoinette they would not submit to the orders of a “mulatto.”

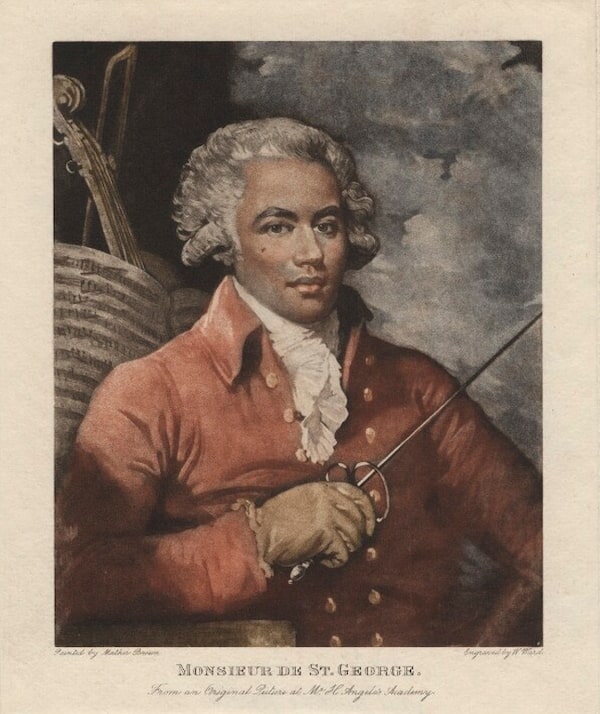

A painting of Joseph Bologne de Saint-George, better known as Chevalier de Saint-George. Born in 1745 on the French island of Guadeloupe, he was a prolific composer of symphonies, concerti, chamber music, and operas.Handout

Little is known about Bologne’s early musical training, but his prodigious talents are thought to have originated with violin lessons in childhood. He caused a stir in Parisian society when, in 1769, he played violin in the new orchestra of François-Joseph Gossec. Marie Antoinette herself attended Bologne’s concerts, and appointed him her music director in 1775.

Bologne would go on to conduct the premiere of Joseph Haydn’s six Paris symphonies, one of many important commissions he made as music director of Concert de la Loge Olympique. He was also a prolific composer – of symphonies, concerti, chamber music, operas and hybrid works fusing instruments and period styles. After a Paris visit in 1779, John Adams called Bologne “the most talented man in Europe in horse-riding, shooting, fencing, dancing and music.” Bologne went on to serve as a colonel of the Légion St.-Georges (the first all-Black regiment in Europe) and died of gangrene in 1799 at the age of 53.

Parallel to Bologne’s fame in Europe was a far uglier reality: Tens of thousands of African people were being trafficked to the French West Indies. At a time when members of the BIPOC community had few if any paths toward emancipation let alone social rank, financial means or any form of privilege, Bologne’s cachet within the worlds of royalty, culture and military life is remarkable; his birthplace of Guadeloupe would itself only get its first Black governor (Félix Éboué) in 1936.

Contemporary interest in the composer has risen alongside an increasing recognition by classical outlets of the need for diversification, with more careful attention being paid to context, narrative and history, and how these elements translate to live performance.

The London Philharmonic Orchestra, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Early Music Vancouver and the Calgary Philharmonic have all performed Bologne’s work. This past February, Chicago-based Haymarket Opera Company released the premiere recording of his opera L’Amant anonyme.

Bologne’s overdue recognition forces a reassessment of not only the culture in which his work was created, but also the environment(s) in which it is currently being programmed and presented.

Those elements came into sharp focus for Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra in 2021, when their 2003 all-Bologne album was reissued. The organization acknowledged that the album’s original title, Le Mozart Noir, “contributed to and facilitated the erasure of Joseph Bologne and his legacy.”

The reissue features a commissioned portrait of the composer by Toronto painter Gordon Shadrach and an essay by American conductor and Bologne scholar Marlon Daniel, who also acted as a consultant on album, now called The Music of Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges. The album’s release was accompanied by a panel discussion and led to an online database run by Tafelmusik filled with essays and links to educational resources.

Providing such information is particularly important given the way in which classical music is presented in many North American educational systems. In Ontario, for instance, the province’s arts curriculum for Grades 1 to 8 suggests classical works as a means of demonstrating genres and concepts, with Vivaldi, Mozart, Stravinsky, Vivaldi and Chopin – but not Bologne – proposed as part of lessons. An e-mail from the Ministry of Education stated that “teachers are encouraged to use materials and compositions that reflect the diversity of musical composition, including those of Canadian and world cultures.”

Some educators will have a chance to introduce students to Bologne this November, when a Young People’s Concert by the Toronto Symphony Orchestra will explore his life and music. If that goes well, perhaps the TSO will be inspired to feature Chevalier as one of their live film-score performances.

Change in the classical world does exist and need only be cultivated. A Hollywood film is just one step, but it may prove to be an important one.