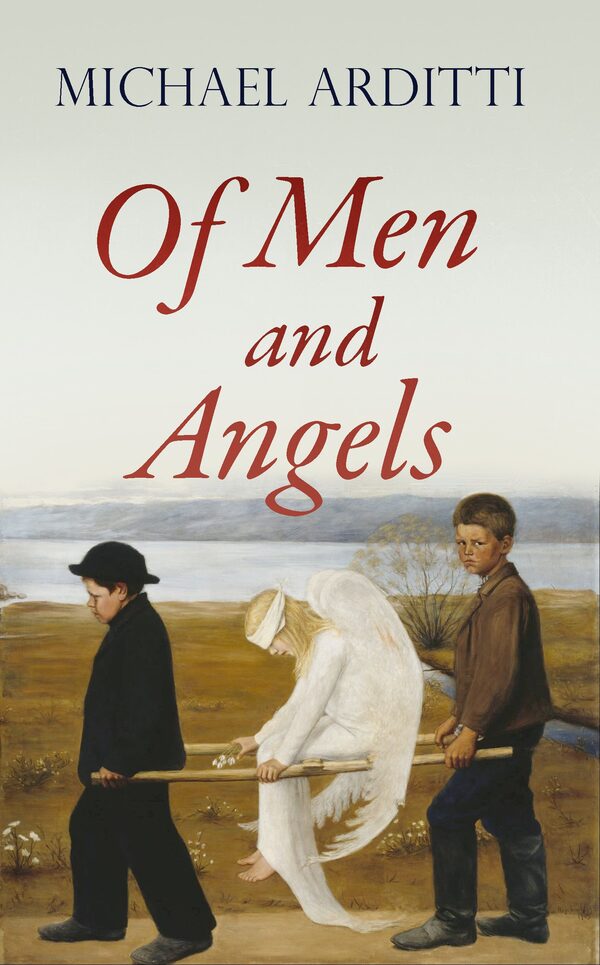

- Of Men and Angels

- By Michael Arditti

- Arcadia Books

- 536 pages

The 1962 movie The Last Days of Sodom and Gomorrah is hardly the finest example of Bible epics. Stewart Granger tries his best as an Old Testament heartthrob, but the script groans and the plot bewilders. For all that, it’s one of the very first lines that earns the film its place in bizarre cinematic history: “Watch out for Sodomite patrols!”

Watch out indeed. Christians have been watching out for a long time, causing incalculable pain, grief and suffering. Today, however, there is open debate within Christian and Jewish theology about the genuine teaching about homosexuality in the Hebrew Scriptures. Many of the most informed, erudite scholars are convinced that faith-based homophobia is a product of tendentious misunderstanding rather than historical and textual accuracy.

Which is where Michael Arditti’s graceful and stylish work of fiction enters the fray. For more than two decades now, the British novelist and critic has been chronicling the influence of faith on our lives in a series of works that subtly sway believer and cynic alike. Of Men and Angels, to a large extent a collection of five novellas around a central theme, follows in that tradition.

In this case, that thread is the story of Sodom, where angels, commanded by God, destroyed the city with fire and brimstone. The elimination of Sodom and its neighbouring city Gomorrah is recorded, of course, in the Book of Genesis, and it’s a story popularly known even in this Biblically indifferent age. It’s why we have the word sodomy and why churches have traditionally supported the persecution of gay people – even now they often oppose LGBTQ rights and marriage equality.

Arditti takes issue with all of that, and with a delicate panache manages to weave modern scholarship into stories that range from the Babylonian exile of ancient Hebrews through a mystery play in medieval York in England, from Renaissance Florence and 19th-century Palestine to Los Angeles during the height of the AIDS crisis. He has angels framing the book, and occasionally whispering the narrative. “Yet just as I cannot but admire your ability to turn timeworn myths into a subtle and enduring theology, so I cannot but deplore the consequences,” says the Archangel Gabriel. “And looking back at the earliest account of events in Sodom, I am amazed at the difference from the story that later became canonical.”

Quite so. Thus we are introduced to Jared, one of the Jews taken to Babylon after Judah’s military defeat. He is chosen to translate the Talmud, and realizes that the original account of Sodom is, in fact, largely lost. He becomes convinced that authentic Jewish values are irreconcilable with the hatred and destruction evinced in this part of Genesis. The Babylon where he lives is far more tolerant than he had been told, and his own sexuality is not condemned as it is in the revised version of Genesis.

And this is the key: Revisionism. What was considered absolute, immutable truth for centuries is now thought to have been edited so as to conform to a new puritanism and a need to distinguish the Jewish people from their powerful, and often seductive, conquerors. Simon Muskham in 15th-century York participates in a local play about Sodom, but comes to see same-sex love as God-given and precious. Frank Archer, the final leading character, is a Hollywood star – echoes of Rock Hudson here – who, while dying with AIDS, begins his last, greatest movie, speaking truth to church power about the reality of Sodom.

It’s all deeply moving and convincing, and one of Arditti’s many strengths is that he doesn’t allow the argument to dominate the humanity. He is convinced, and I agree with him, that the sin of Sodom concerns the rejection of the stranger, lack of hospitality, greed and mistrust of God. But he is disarmingly subtle in using this as a subtext, lived and breathed through his various characters. He is about storytelling and not propaganda; he is implicit rather than didactic.

On one level this is a novel of human failing and fragility, a splendid observation of our needs and desires, our triumphs and failings, told through the prism of history. On the other, however, it’s a roaring indictment of the obsessive hostility toward homosexuality that even today flows through the bloodstream of the church body like a toxin. It’s the combination of these two literary brothers-in-arms that makes Of Men and Angels so compelling, and so vitally important.

Michael Coren is the author of The Future of Catholicism, Why Catholics Are Right and Epiphany: A Christian’s Change of Heart and Mind Over Same-Sex Marriage.