ASSOCIATED PRESS

He's had many names and identities in his long musical career, but his impact on pop music has been unique and undeniable. The pop star Prince was found dead at his Minneapolis home on April 21, 2016. He was 57.

In 1996, The Globe's Elizabeth Renzetti caught up with the artist (who then styled himself The Artist) about the release of his three-CD opus Emancipation. Here's her account of their conversation, reprinted from The Globe's archives.

The worker bees swarm around, desperate to make life easy for their queen, who used to be known as Prince. Their buzzing fills the suite adjacent to his: How is he handling this? How does he look? Has anyone upset him?

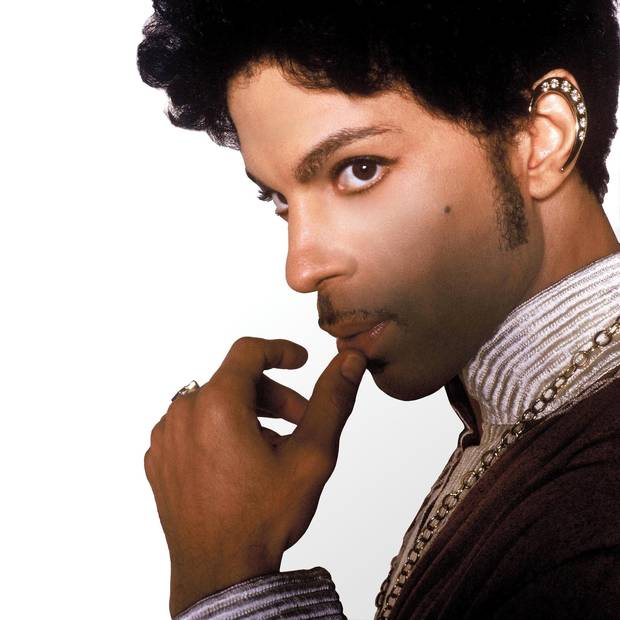

A large drone stands outside the royal chamber, opening the door to a series of sanctioned petitioners. Inside, there's a pocket of silence around the little sack of testosterone formerly known as Prince and now known only, in a fit of hubris no one else finds shocking, as The Artist. That's right: The Artist, and you'd better say it with a straight face.

A good case can be made – and has been made by the former Prince – that if anyone in the modern rock era deserves that definite article, it's him. He is often described as a genius for his ability to make records (on which he plays most of the instruments) that are great, operatic washes of soul and funk.

Like Elvis before him, and Michael Jackson alongside, Prince has put great energy into the development and promotion of his own myth, singing with equal fervour his own praises, the praise of God and the lovely ladies who stroked him along the way. He might be the only performer who borrows freely from the past, but manages never to sound like anyone but himself.

What he hasn't done, at least until the release of his current three-CD epic, Emancipation, is talk. His public appearances, apart from the legendary bump-and-drool of his live concerts, have been grudgingly parcelled out – a Letterman here, a Rolling Stone interview there. Now, however, The Artist needs Promotion, so he's on the road.

Perhaps because he's never really subjected himself to the interview process, he's not adept at the start/sound bite/goodbye routine mastered by other pop stars. The 38-year-old is good at having a conversation, at probing in return. He is willing to discuss his escape from his contract with Warner Brothers (hence the title of his disc), his recent blessed union with wife Mayte Garcia, and the connection between faith and sexual fulfilment.

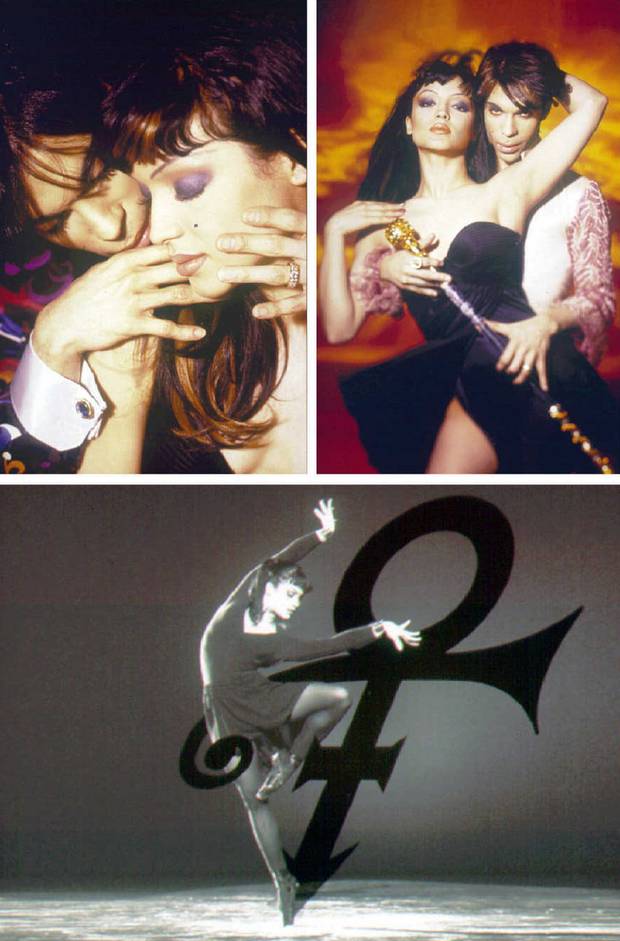

Prince and his fiancée, Mayte Garcia, are shown in these undated handout photos prior to their wedding on Feb. 14, 1996. The two divorced in 1999.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

He will not allow conversations to be taped – he used to even forbid pen and paper – because he feels "you get more from the vibe," and because his conversations have ended up as bootleg records. Neither will he discuss his personal life: It has been widely rumoured in the tabloid media that the baby he recently had with Garcia was born with severe birth defects and subsequently died. "I don't talk about home life," he says. "That falls into the private category."

If it's true, then his behaviour is strangely lighthearted in the face of such news. It's especially poignant considering that he milked his family for inspiration on the new record: Friend, Lover, Sister, Mother/Wife is a lush ode to Garcia, whom he married on Valentine's Day, and the funkier Sex in the Summer features an ultrasound sample of his baby's heartbeat.

Mainly he wants to talk freedom – from his record contract, from his demons, from the need to make disturbing records like his last effort, a contractual obligation album called Chaos and Disorder, which he doubts he will ever listen to again.

"I've been emancipated in my heart and my attitudes toward everything," he says in a voice that's surprisingly deep and rich for a man who often sings in Jeanette MacDonald falsetto. It's a strange voice coming from a guy of such teeny stature: he's so small you're afraid you'll step on him, so small it feels as if you could put him in your pocket. Small but improbably beautiful, if you can get past the goatee that looks like a 14-year-old's first attempt at facial hair.

He really, really wants everyone to know how good this record is; a plague of self-doubt has not landed on this man's house. Of Emancipation, he says, "This is one of my best moments, if not my best moment," and later, "I listen to it and I'm sort of awestruck."

While such statements make you want to take a fly swatter to him, the truth is that the record – three discs of 12 songs, each disc exactly an hour long – has left many in awe at the grandness of his plans, and his ability to carry them out. The studied triangularity of Emancipation, recorded over a year at his Paisley Park studio in Minneapolis, is deliberate; he wanted to make something perfectly formed, "something that would have frightened me if another artist had done it."

On this record, as on previous ones, he is adept at blending the sacred and the sexy, though he disingenuously defends his famous songs against charges that they are profane.

Pussy Control, from his 1995 Gold Experience record – which he coyly refers to in conversation as "P Control" – is about women taking charge of their sexuality, he says. Another song, Sexy MF (the MF is spelled out in the song, and it doesn't stand for milk-fed), is about "monogamy and marriage." We don't get into the subtext of Cream.

To him, the connection between grinding your hips and falling on your knees is obvious, and integrated in his music. "You don't think God is sexy?" he asks, sounding genuinely bemused. "When you have faith, serotonin starts pumping in your brain. It's the same as when you have an orgasm."

He is told that the Rev. Al Green, the great soul singer, talks about the spirit moving him when he sings for the Lord. This brings out the salacious, jive-talking Prince of priapism, and he leaps out of his chair to slap the floor. "Oooh, but that didn't stop him from having boiling grits poured down his back! That didn't stop him from chasing other people's wives!"

To hear him tell it, he has force-fed the spirit into others, like the unnamed music journalist who came to interview him at Paisley Park. Again Prince leaps up, does a spin on his high-heeled yellow boots – just like in the video for Little Red Corvette – and mimics getting the critic in a headlock. "I said to him, 'Do you believe in God?' And he says, 'No.' And I say, 'Do you believe in faith? In hope?' By the end of it, Blood was down on his knees, looking for a church to go pray."

Perhaps that writer had disturbed him by making reference to the ridiculous name change that took place in 1993, when Prince became The Artist Formerly Known As, and legally changed his name to a symbol that resembles a defective pretzel. (He's serious about that glyph – not only does he have a symbol-shaped guitar, but it's present in the little metal toggles on his suede boots). He said at the time that the name Prince carried "too much baggage" but he was still sufficiently attached to it to block Canadian musician Bob Wiseman's joking attempt to change his name to Prince.

His fluid identity flowed in an ever-weirder direction recently, when he took to appearing on stage with the word "Slave" written on his face, a serious comment from anyone, but shocking from a black American, considering the historical implications. Perhaps shock is what it was about, essentially – it would certainly not have been this first time in his career he took glee in provoking.

"Slave" was a comment on his contract with Warner Brothers, the company he'd been recording with for almost 20 years. The industry buzz is that a musician who was both prolific and expensive was a heavy financial burden: The company wanted fewer records so they would have to pay fewer advances and could promote each one better, perhaps even get him back to the superstar level of 1984's smash Purple Rain soundtrack.

He's wiggled out of that contract now, and is willing to be magnanimous to his former employer. "There is a value in an institution like that," he says. "There are people who don't want to own their work, they want to sell it for a gold record. That's not what I want." In a November interview with Rolling Stone, he provided a pointed aphorism to illustrate his situation with Warner, which owns the masters to his previous records. "If you don't own your masters, your master owns you."

He comes back to the issue a little later, eager to explain his complicity in the whole mess. "Understand, you can make yourself a slave," he says. "I used to say to people, 'Do you love me?' And they'd say, 'Of course we do.' And I'd say, 'Then can you help me get this off my face?'"

Now, he insists, releasing records on his own NPG label has freed him from the constrictions of charts and hits and number of radio-station spins. "Every time I hear the word 'commercial' my blood starts percolating," he says. "I don't need more money. I already have a lot of money."

And what can money buy? No, not height. Freedom. That's what he had to sweat for, and that's what he hears when he puts on his new opus. "I recorded in freedom, so you hear the sound of freedom on the record. Happiness from track to track."

End of a purple reign: Pop superstar Prince dead at 57

0:47