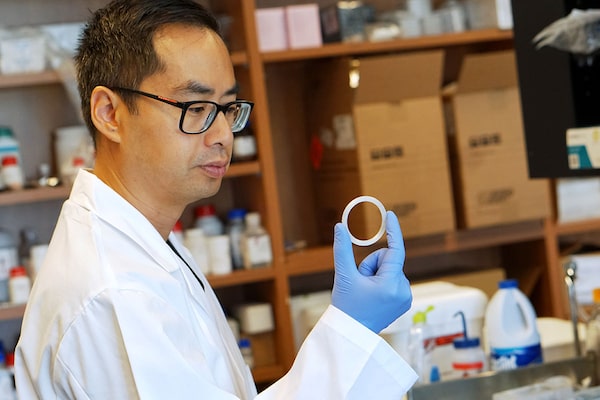

Dr. Emmanuel Ho, associate professor at University of Waterloo’s School of Pharmacy, with 3-D printed drug delivery device.SUPPLIED

Pioneering researchers are looking to the burgeoning world of 3-D printing to devise new drug delivery options that are more precise, cost-effective and accessible than traditional forms.

One of these innovators is Dr. Emmanuel Ho, an associate professor at the University of Waterloo School of Pharmacy and an international expert in nanomedicine.

Dr. Ho’s goal is to deliver a 3-D-printed, intra-vaginal ring that would provide highly precise doses of medication to protect women from getting HIV, the virus that causes AIDS and kills one million people globally each year, according to UNAIDS.

“Why take [the drugs] orally where they can go everywhere in the body, if we can actually stop HIV at the site of transmission?” Dr. Ho says. “We can potentially deliver a product that is more effective, and we can also reduce [the drug’s] side effects.”

Dr. Ho and his team hope the IVR will become a viable option for women in the fight against HIV and AIDS. According to UNAIDS, of the 36.9 million people globally who were living with HIV in 2017, 19.6 million of them were living in eastern and southern Africa, and 6.1 million in western and central Africa. In sub-Saharan Africa, three out of four new infections among adolescents aged 15-19 are girls. Young women aged 15-24 are twice as likely to be living with HIV than men. By leveraging powerful pharmaceutical research, rapidly developing 3-D printing innovations and the University of Waterloo’s unique position as a leader in Canadian research, Dr. Ho aims to introduce a more effective, affordable drug delivery tool to areas of the world that need it the most.

Dr. Emmanuel Ho with members of his team in his University of Waterloo research lab.SUPPLIED

The IVR is made of medical-grade plastic with hollow tubing and tiny pores. Medicine is loaded into the ring, which is then placed in the vaginal tract, where it slowly disseminates drugs through its porous material to be absorbed by the area.

Dr. Ho is currently testing the delivery of a combination of anti-HIV and anti-inflammatory drugs through the IVR. According to Dr. Keith Fowke, professor and head of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases at the University of Manitoba and one of Dr. Ho’s collaborators, inflammation in the genital tract increases one’s risk of acquiring HIV, because it draws the immune cells that are infected by HIV into the area. Releasing anti-inflammation medication directly in the tract could mitigate this risk.

“If a woman has high levels of inflammation in the genital tract, then the probability of HIV infection is much higher,” Dr. Fowke says.

This model could be adapted to deliver a variety of medications beyond the HIV prevention drugs that are currently being tested. In fact, the team hopes to use the IVR to deliver hormonal contraceptives since the device is capable of holding more than one drug at once.

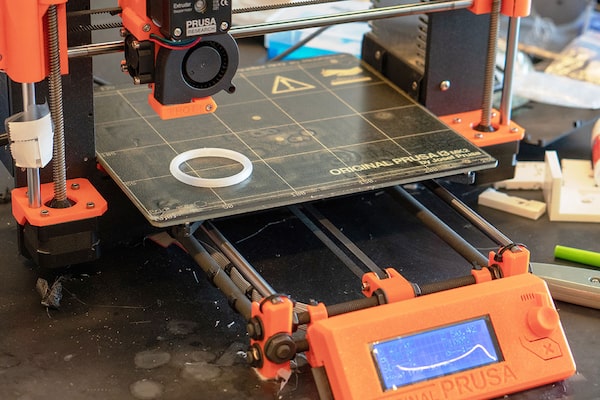

Dr. Ho says that while rings of similar shape and design, such as the NuvaRing, have already been approved for birth control and hormone replacement therapy, developing a 3-D-printed model will allow for more precise design and drug delivery through very small pores in the ring’s exterior.

Another benefit of 3-D printing is cost reduction, Dr. Ho notes. With conventional ‘hotmelt’ injection molding, polymers are poured into an aluminum mold, creating ‘dead spaces’ in the mold where material could get stuck and be wasted, he says. With 3-D printing, that kind of waste is eliminated.

3-D printed intra-vaginal ring (IVR) prototype on 3-D printer in Dr. Ho’s lab.SUPPLIED

3-D printing’s ability to achieve very complex geometries makes it optimal for projects like Dr. Ho’s IVR, says Conner Janeteas, medical applications specialist at Cimetrix Solutions. In his work at the division of Oakville, Ontario-based Javelin Technologies, a leading 3-D design engineering and solutions provider across Canada, Janeteas consults with hospitals, universities and research organizations about medical applications of 3-D printing. He says he’s excited about the technology’s potential to revolutionize processes like drug delivery.

While traditional manufacturing might be able to achieve similar results, he says, with 3-D printing you get more design freedom.

“With 3-D printing … you don't have those design compromises that you would normally,” Janeteas says. “You can just design for optimal outcome and rely on the technology to help make that feasible.”

“The potential impact on the medical community [would be] astronomical,” he says. “There are many ways that this technology could be used to improve patient outcomes right now.”

And while an IVR is unlikely to eliminate pills from the medical realm, it could provide women more choice.

“Having more options is always more beneficial,” Dr. Ho says.

Advertising feature produced by Globe Content Studio. The Globe’s editorial department was not involved.