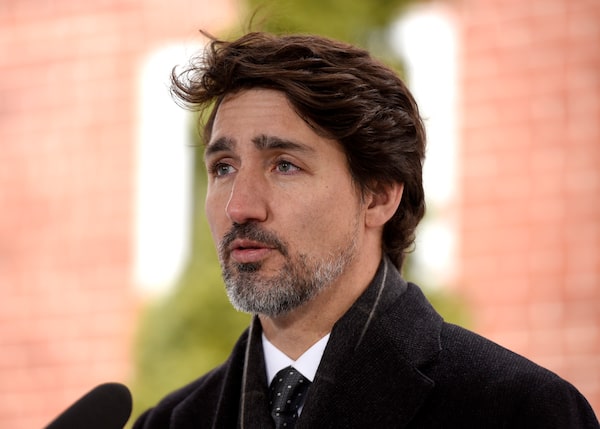

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau speaks during his daily press conference on the COVID-19 pandemic outside of his residence at Rideau Cottage in Ottawa, on April 10, 2020.Justin Tang/The Canadian Press

The people running governments are among the few in this country who don’t have much time, during the biggest crisis since the Second World War, to sit around and contemplate what the economy will look like on the other side of it.

That’s a problem, because they’re also among those who will soon have the most opportunity to shape the way Canada adapts to unprecedented disruptions and lasting implications for its industry, workforce, trade relationships and so much else.

For now, the focus of the most powerful people in Ottawa – the Prime Minister and his staff, most top ministers and bureaucrats – is day to day, if not minute to minute. That’s as it should be: The combined tasks of minimizing lives lost to COVID-19, and limiting economic devastation caused by the health measures, require an urgency previously beyond wildest imaginations.

But we’re not that far away – months, presumably, though nobody knows how many – from the point at which governments will be pressed to roll out policies to shape the economic recovery. And starting around now, serious thought should be given to what policy levers might be needed then.

For Justin Trudeau’s government to have the capacity to do that, it will have to further break from the way things normally operate.

Centralization of political decision-making in the hands of a few officials in the Prime Minister’s Office, a trend for decades, has rarely been more at odds with public-policy imperatives.

Those officials are currently being exhausted managing immediate needs, and don’t have much time to engage with those outside the office who might give thought to anything beyond what happens tomorrow. The same applies to ministers, most notably Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland, nearest the centre of power.

In terms of political leadership, there are some possibly encouraging early indications of delegation. Government officials have indicated that reasonably senior cabinet members who are not as involved in the immediate pandemic response – such as Infrastructure Minister Catherine McKenna and Environment Minister Jonathan Wilkinson – have been tasked with giving thought to eventual stimulus measures to help restart the economy, and how they might fit into the clean-growth agenda, which, until about a month ago, was seen as Mr. Trudeau’s defining priority.

But even if they’re able to move that discussion along (absent the usual level of PMO involvement), there stand to be many more – and more unusual – economic factors for policymakers to wrap their heads around, coming out of this massive disruption.

There is the question of how the workforce is being reshaped – by the accelerated decline of some sectors, the rise of others, the havoc wreaked on members of the gig economy. What new supports, from revamped employment insurance to retraining programs to workplace regulations, might be needed beyond the next few months?

There is the unknown extent to which months of Canadians working and receiving services remotely will lead to a lasting surge in digitization. What sort of help might be needed by businesses to adapt, individuals to ensure access, or consumers in terms of privacy protections?

There are the newly exposed vulnerabilities in our supply chains – the sudden shakiness of an integrated continental economy, the impacts of tightened borders around the world. Will this enormous setback for globalization necessitate different trade or industrial policies?

It’s impossible to do the full calculus on these or other equations, just yet. There are so many variables, especially around when the economic shutdown ends in Canada and elsewhere, and how gradually society returns to something approaching normalcy.

But if nobody can be expected to have all the answers, there’s a need to at least starting to work toward them, lest a possible economic reset be conducted totally on the fly. And there are various ways to get the ball rolling.

One of them is to send elected officials out pounding the pavement (or at least Zoom) in search of insights, as Ontario Premier Doug Ford seemed to do late this week when he announced that roughly half his cabinet will serve on a “Jobs and Recovery” committee tasked with consulting business and civic leaders. Such efforts risk being feel-good listening tours, but they may have advantages in transparency and avoiding perspectives being overlooked. (In a federal minority parliament, they could also be a way to engage opposition parties, if the government were so inclined.)

Another is to rely more on the public service, which may be happening somewhat in Ottawa: Several sources, whom the Globe granted confidentiality because they were not authorized to speak for the government, said that Clerk of the Privy Council Ian Shugart is assigning other bureaucrats to start plotting out road-to-recovery options. The bureaucracy has some reputation for risk aversion and overreliance on existing policy mechanisms, but should at least know where government is capable of quickly implementing impactful policies.

A third, which would play to inclinations Mr. Trudeau showed in his earlier days in office, is to appoint an outside panel of leading lights from business, academia and elsewhere – or several such panels, to get beyond broadstrokes by tackling each big recovery question in more detail. Reports they produced would run a familiar risk of gathering dust, but they also could be the best way of giving licence to fresh thinking outside of government’s current framework.

The hope has to be that whatever processes are set in motion now, they’re ones that allow for a maximizing of brainpower, from a wide swath of people, afforded more leeway and trust than usual.

When it comes time to lock in the recovery policies, it may be the same relatively few people at the centre of power making most of the decisions. But they’re going to need others to lay some groundwork, soon, if government is to be prepared for economic imperatives and opportunities of the reopened world.

Adam Radwanski

Adam Radwanski