sam island/The Globe and Mail

The young influencer’s pose is both iconic and ubiquitous: Modelling a fashionable sundress, she turns one way and then the other, with only the presence of the smartphone held steadily at collar-bone level to indicate the snippet is a selfie shot in front of a mirror.

What differentiates this clip from countless others on Instagram, TikTok or other social media platforms, however, is the presence of a “Buy Now” button on the screen that enables the viewer to instantly purchase the dress. The clip is part of a series, each with the same young woman modelling different items, which originated in a livestream broadcast—the weird re-emergence of appointment TV’s immensely popular shopping channel offerings, but projected out into the boundlessness of e-commerce.

On burgeoning platforms like WhatNot, a so-called “live shopping” marketplace, consumers can tune in to hundreds of such promotions, each featuring influencers pitching a wide range of products—everything from cosmetics to action figures—in real time. Geoffroy Robin, chief operating officer of Montreal-based Livescale Technologies, a six-year-old company that offers live shopping services to global brands like L’Oreal, says a rapidly growing number of vendors are embedding “live” into their own websites, many featuring pros with experience selling on live TV who can host “events.” In Asia, he adds, some will do 12 to 14 events per day.

This hybrid channel, he explains, surfaced before 2020 but was turbocharged by the enforced isolation of the pandemic and seems to have become a staple of consumerism in Asia. “This is a solution that is merging and unifying retail and e-commerce,” Robin says. “What we’ve seen before the pandemic is that among our clients, these teams were working in separate silos. Live shopping is really putting the glue in between these two teams.”

The global retail sector has operated in a state of permanent discombobulation ever since a meteor named Jeff Bezos fell to Earth and killed off those dinosaurs we once knew as department stores. This particular fad, which may be the next megatrend, seems to be the latest chapter in the long-running narrative about how we shop.

Canadian brands and retailers should take note. “Livestreaming shopping is an emerging business,” says Ruhai Wu, an associate professor of marketing at McMaster University’s DeGroote School of Business. “The growth speed is fascinating.” Indeed, live shopping sales in China exceeded $US500 billion in 2022 (up from US$18 billion annually in 2018 or 2019) and accounts for as much as one-fifth of Chinese e-commerce, according to some estimates. Live shopping revenue in the U.S. currently stands at about US$50 billion and is predicted to grow, albeit more slowly, says Wu.

For those so inclined, there are now dozens of live shopping platforms and apps, as well as the inevitable lists of top live shopping sites and online explainers filled with advice that’s both helpfully specific (“Partner with the right influencers”) as well as impossibly general (“Strategize your on-platform selling approach”). Service firms like Livescale, which offer live shopping services for big brands, scout for influencers, provide technical support and help vendors create “engagement,” such as polls, chat or other features.

This story begins with the deafening noise in e-commerce, which is nothing new. Searching any platform site, but especially the likes of eBay and Amazon, yields a list of options as daunting as any Google search. And the consumer decision-making process is complicated by the myriad ways in which both platforms and vendors have muddied the digital waters with fake reviews, gamed ratings and, in Amazon’s case, algorithms that preference the company’s white-label brands or those that have paid to make sure their goods float to the top of a search.

“It’s against this backdrop that live e-commerce has a huge role to play by maybe making it easier for you to find the right product by having more authoritative sources—like a livestreamer—tell you where to go,” says Shreyas Sekar, an associate professor of management at U of T’s Rotman School of Management. Influencers have a built-in incentive to be fairly straightforward with their audience, says Sekar, because they risk losing followers if the recommendations turn out to be duds.

The consumer appeal, says Wu, has a few layers, none of them all that new. The immediacy of a livestream video showing an actual human being demonstrating a product is a kind of relatable and enticing antidote to the firehose of the big platforms. At this relatively early stage of live shopping’s evolution, there are also a lot of rank amateurs, so the videos have an appealing DIY quality: They tend not to be slick, and the production values are, well—think Crazy David’s cheesy carpet ads from back in the day, or anything Bad Boy has ever done.

Yet as Robin points out, the trick to live shopping isn’t just about content; it’s about shifting consumer behaviour. “The audience needs to get used to this type of transaction,” he says. “We talk about habits and creating the habit among the audience overall for livestream [shopping] to keep growing in the West.”

Wu has observed three approaches to live shopping in the Chinese market: those run by the employees of smaller e-commerce sites; ones featuring celebrities; and clips churned out by professional influencers to their followers. In terms of the latter, some will be sponsored by brands. Robin adds that his firm and others basically offer white-label solutions to brands: live shopping events that stream on brand websites, but are produced separately.

The techniques and strategies are also evolving rapidly, a kind of highly dispersed trial-and-error process to determine whether the live shopping sweet spot is, say, an impulse buy—cool sunglasses!—or the pointy end of a multichannel digital marketing strategy that includes a lot of pushing elsewhere on social media.

Different sites are experimenting with the optimal time of day to hold live shopping events—7 p.m. to 11 p.m. is the most popular—but Wu’s research team has also gathered evidence suggesting that savvy influencers tend not to use a static time slot. “We’ve found that when they stick to a consistent schedule, the show’s performance actually drops.”

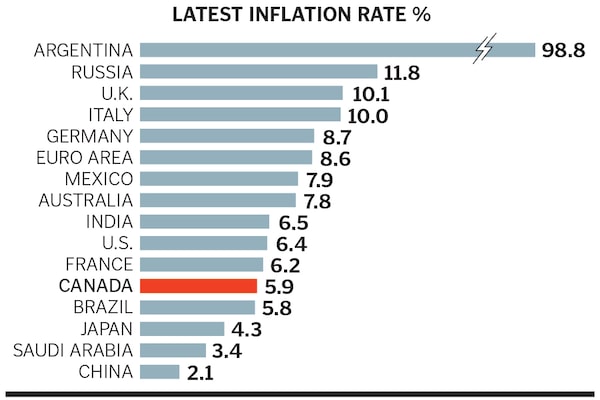

Then there’s the payments technology piece. “Online cash transfers and digital transfers picked up very early in China, but they were picked up much more slowly in the West,” says Sekar. “China is leaps and bounds ahead of the U.S. and Canada when it comes to innovating in e-commerce.”

The e-commerce giants, needless to say, are acutely aware of the potential existential threat posed by live shopping, and most have introduced features that allow consumers and influencers to create and access such events. Facebook, whose Marketplace has become a huge buy-sell space frequented by younger consumers, is trialling its live shopping service in the U.S. and Thailand, while Shopify and Amazon have both launched their own versions.

Facebook has even published a livestream shopping “mobile onboard guide,” which walks users through the back-end and set-up steps, and includes helpful advice like, “Pro tip: We recommend posting to your timeline because many people watch live shopping videos after the event has happened.” Live, it would seem, needn’t be taken literally.

It remains to be seen whether this variant of e-commerce catches on in Canada, which was notoriously slow to twig to e-commerce. Robin urges retailers and vendors to experiment with this channel, and to try out a handful of live shopping events to see what sticks. “You can easily go live with just a smartphone,” he says.

This emerging approach, predicts Wu, “will re-shape the whole retail industry, absolutely.” Large players like Walmart and Best Buy are being forced to respond, but he adds that small bricks-and-mortar businesses, including those that discovered Shopify in recent years, shouldn’t overlook both the risk and the potential.

Those small vendors and their employees need to change their jobs, says Wu: “They need to become influencers.” As Sekar jokes, “Maybe we’ll all become livestream suppliers.” /John Lorinc

The Globe and Mail

Your time is valuable. Have the Top Business Headlines newsletter conveniently delivered to your inbox in the morning or evening. Sign up today.