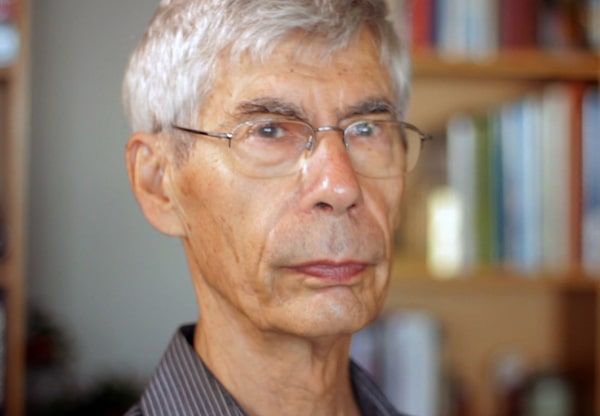

Former journalist Peter Trueman.Courtesy of Global News

Peter Trueman, who died on July 23 in Toronto at age 86, was the original news anchor for Global News and was a widely respected Canadian broadcast personality during the 1970s and 1980s. Far more than a talking head, he came to the job with a solid background as a print reporter – he covered the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 for the old Montreal Star – and he knew television news and documentary production from his years at the CBC.

William Peter Main Trueman was born on Christmas Day in 1934, in Sackville, N.B., to Jean (née Miller) and Albert Trueman. His father was a high school teacher and an academic administrator at the University of New Brunswick, who went on to work the University of Manitoba and later the University of Western Ontario and Carleton University. The elder Mr. Trueman became a major cultural figure as the first national director of the Canada Council and posts at the National Film Board and CBC.

His father’s succession of jobs meant young Peter went to school in Sackville, Fredericton, then Winnipeg. He started university at UNB and transferred to Carleton University in Ottawa when his family moved there. At Carleton, he became obsessed with James Joyce’s novel Ulysses and never graduated. Instead, he landed a job at the Ottawa Journal as a general gofer in the newsroom when he was about 20. He must have impressed somebody because he soon became a junior reporter.

At the Ottawa Journal, he met Eleanor Wark, the managing editor’s secretary. By this time he was working as an overnight police reporter.

“So our courtship took place from 5 p.m., when I finished work, until 9, when he started work,” Eleanor Trueman recalled. The couple married in Ottawa and then moved to Montreal, where Mr. Trueman started work at the Montreal Star, the largest English-language daily in the city. He was in his early 20s in 1957 when the Star sent him to New York to become a U.S. correspondent. His wife said she thought she, “had died and gone to heaven.”

Global News TV anchors Jan Tennant and Mr. Trueman in 1982.Courtesy of Global News

From New York and later Washington, Mr. Trueman covered the United States, interviewing celebrities, covering the United Nations and the dramatic 1960 presidential election where John F. Kennedy defeated vice-president Richard Nixon. But the most dramatic ongoing story was civil rights and the marches, murders and violent police actions against demonstrators in the southern United States. Mr. Trueman saw Birmingham, Ala., police chief Bull Connor attack demonstrators. He wrote about how the police stood aside as locals beat civil-rights protesters known as Freedom Riders.

“He was shocked and revolted by what he found in the south,” Mrs. Trueman said. “That was a story that really mattered to him.”

After five years in the United States, Mr. Trueman returned to Canada to work for the Toronto Star. He was there for about three years and worked briefly as national director of the United Nations Association in Canada. He soon returned to journalism, working at the CBC. An experienced print reporter, he soon learned the techniques of matching words to pictures.

After a few years, he was named the CBC’s chief news editor. He was in that job during the 1970 October Crisis, when the Front de libération du Québec kidnapped British diplomat James Cross and Quebec cabinet minister Pierre Laporte, who was later killed.

Mr. Trueman was impressed with the coverage of the bilingual Montreal reporter Peter Daniel, and in 1971 named him as the CBC’s Paris correspondent.

“Peter was really approachable. You could talk to him; it wasn’t like he was the boss and you were the underling,” Mr. Daniel said.

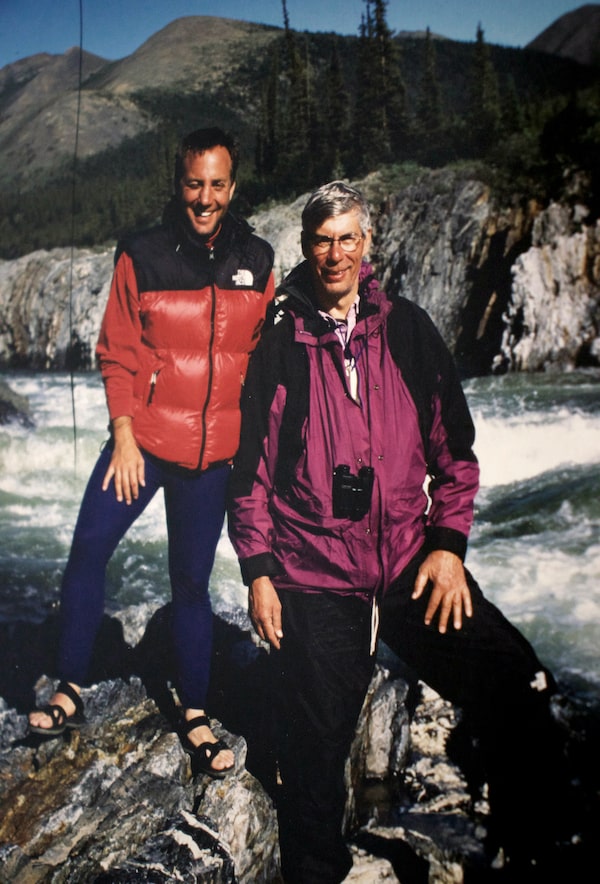

Mr. Trueman, right, and Mitch Azaria on the Firth River in the Yukon, 1997.Good Earth Productions

The pinnacle of Mr. Trueman’s career was when he became the anchor at Global in 1974, then a new television network. He was hired by Bill Cunningham, who knew him from the CBC.

“I hired him after I heard him narrate a program on the CBC. He had a fine voice and was a great writer and excellent broadcaster. He was a good-looking guy and very fit,” Mr. Cunningham recalled.

At the end of his newscast, Mr. Trueman would give a short commentary, which always ended with the phrase: “That’s not news, but that, too, is reality.” The line was written by Mr. Cunningham, and Mr. Trueman was never that happy with it. His ideal would have been all news, no commentary.

In private life, Mr. Trueman was modest and found fame uncomfortable. He was embarrassed when on vacation in London. He was riding up an escalator with his wife in Selfridges department store when a Canadian on the down escalator recognized him and shouted out his “that, too, is reality” line. “Peter just cringed at that. He didn’t enjoy the celebrity aspect of his job,” his wife said.

One thing that made his commentary popular with the public was that it was even-handed.

“Peter did not have a political point of view. And he gave Global the gravitas it needed. We called him the preacher in the newsroom,” said Ray Heard, who succeeded Mr. Cunningham as vice-president of news at Global. “Peter had a wonderful way with people. He was never confrontational. And he mentored a lot of younger people in the newsroom.”

The Global News team. The pinnacle of Mr. Trueman’s career was when he became the anchor at Global in 1974, then a new television network.Courtesy of Global News

Global hired a second anchor to work with Mr. Trueman, Jan Tennant, who had been the first woman to read the news on CBC’s The National.

“Peter was an absolute gem on the desk. I know he presented himself to the public as a serious man, but he was wonderful to work with,” Ms. Tennant said. “I think Peter relaxed in our format. He didn’t like the idea there was a performance involved in news. And, of course, there is. You have to do things on cue.”

The two were a ratings success, Mr. Heard said, as Canada’s first male-female anchor team.

While he was still reading the news at Global, Mr. Trueman wrote Smoke and Mirrors: The Inside Story of Television News in Canada, a 1980 book that was highly critical of his industry.

“It’s seldom that one of TV’s own goes further and bites deeper than its critics,” Blaik Kirby noted in his review of the book in The Globe and Mail. Mr. Kirby described Mr Trueman as “perhaps the ideal person to write a book on the inside story of television news in Canada.”

Mr. Trueman quit drinking early in life and, for the last 51 years, was a member of Alcoholics Anonymous. Half a century ago, drinking was a regular part of life in journalism, including at the CBC, where he was working when he quit. Mr. Trueman used to speak at AA meetings and would go to prisons to talk about alcoholism to inmates.

When Mr. Trueman left his news-reading job at Global in 1988, he and his wife moved to Amherst Island, a bucolic spot in Lake Ontario connected by ferry to Bath, Ont., near Kingston.

Mr. Trueman had been retired for about five years when one of the young men he had mentored at Global News went to visit him on Amherst Island. Mitch Azaria worked as a junior in the newsroom.

“At Global, I was at the bottom of the food chain, but Peter was approachable,” Mr. Azaria said.

That day, Mr. Azaria told Mr. Trueman that his tiny production company – run by Mr. Azaria and his wife – had sold the idea of a series on Canada’s National Parks to the Discovery Channel, but there was a competition with some big players.

“Peter was in right away. And we won the contest because of what Peter brought to it,” Mr. Azaria said. It was the perfect job for him since he loved wildlife and conservation.

The team produced 70 programs named Great Canadian Parks that ran on the Discovery Channel for five years, and for much of that time, it was a top-rated program. Mr. Trueman was the face of the program and the main writer.

“Peter loved it. He figured it was the best job he ever had,” Mrs. Trueman said.

One thing he loved about it was travelling to so many remote parts of Canada.

“I bet he’s seen more of Canada than any person on the planet,” Mr. Azaria said.

Like his signature closings on the Global newscast, Mr. Trueman ended his park pieces with a short homily. Here is the one from Ellesmere Island:

“Most of us will never be in a wilder place than this. Ellesmere Island National Park Reserve is not just north of 60 but north of 80. Flying here is very costly, and visitors must bring with them everything they’re going to need during their stay. The nearest store and the nearest doctor is nearly 1,000 kilometres away, three to four hours by air. But this does not seem to worry visitors unduly. They’re too caught up in the power and the mystery of the place.”

Mr. Trueman later did some consulting for documentary projects. In 2001, he was named an officer of the Order of Canada, as was his father before him.

All his life Mr. Trueman was a keen photographer. He was tall, at 6 foot 5. “Apart from home, he never had a bed that fit him,” Mrs. Trueman said. It was a problem for a man who spent so much time on the road.

After 23 years, the couple left Amherst Island a dozen years ago and moved to Toronto to be closer to their children.

In addition to his wife, Mr. Trueman leaves their children, Anne, Mark and Victoria, as well as 11 grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.