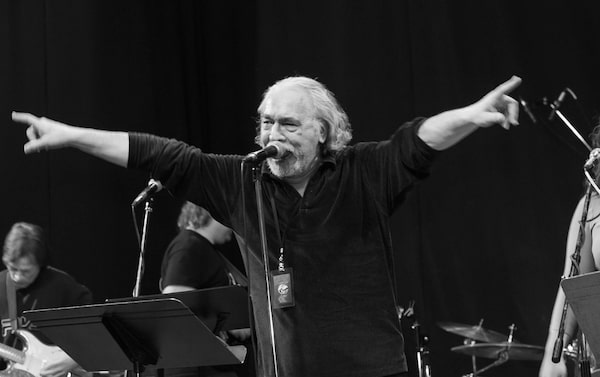

Bob Segarini brought a gravelled voice and a wealth of rock ‘n’ roll experience and knowledge to his work as a musician and DJ at Toronto radio stations.Barry Roden/Handout

On Aug. 21, 1987, DJ Bob Segarini showed up late again for his afternoon shift at Toronto rock station Q107. The excuse on this occasion? He said the sun was in his eyes on the drive in.

The good news was that the sun would be at his back for the drive home. The bad news was that he was fired.

“It’s the one unforgivable thing in radio,” former Q107 program director Bob Mackowycz told The Globe and Mail. “When your theme music goes, you’re on the air.”

It was Mr. Mackowycz who fired his friend and one-time on-air partner Mr. Segarini, an irrepressible freewheeler known as the Iceman.

The Iceman would cometh and goeth, never lasting very long at his jobs. “Bob was a force of nature,” Mr. Mackowycz said. “If he had brought any kind of discipline along with his talent, he could have been one of the all-time greats.

Mr. Segarini, a rambunctious radio personality and a gifted song-writing musician who led a chaotic life colourfully, died at Etobicoke General Hospital on July 10, after three months there. A diabetic, he was 77.

He brought to radio a gravelled voice and a wealth of rock ‘n’ roll experience and knowledge. In various bands, the California-born musician had toured as the opening act for the Doors, the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane. He befriended and co-wrote with Harry Nilsson, played an electric drill on Brian Wilson’s original Smile sessions, and had his songs recorded by Wayne Newton and Jose Feliciano.

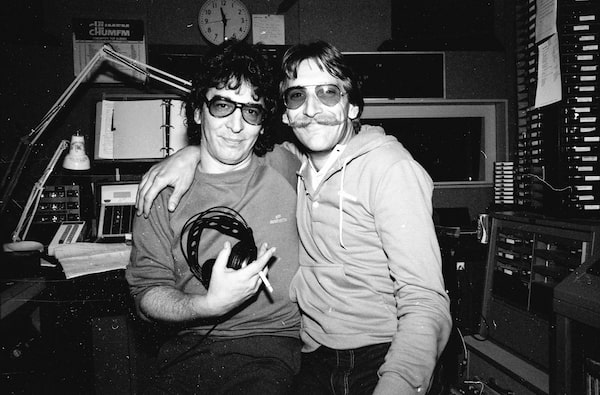

Bob Segarini, left, and Gord James in 1981.Barry Roden/Handout

He wrote the theme to the Canadian children’s television program The Edison Twins and two songs he co-wrote appear on the soundtrack to the 1971 feature film The Vanishing Point.

The self-described “minor-league rock star” came to Canada in the early 1970s as a member of the Wackers, an American group that quickly developed an avid following in Montreal during a month-long residency at Norm Silver’s Mustache club. He fell in love with the city – his affection for smoked-meat sandwiches endured the rest of his life – and with the country.

He also became an indefatigable champion for Canadian musicians. “Bob took time to listen to them, discover them and promote them,” his long-time friend Pat Blythe said. “He loved to see people fly.”

Bob Segarini, right, interviewing Lemmy and Phil Taylor from Motorhead in 1981.Barry Roden/Handout

Mr. Segarini’s radio career began in the early 1980s, when he was hired to jockey discs at Toronto’s CHUM-FM. He lasted just six months. He was canned for turning what was supposed to be a short interview with Lemmy Kilmister and the band Motörhead into a sprawling, three-hour session that included the playing of old R&B records that were banned from the station’s playlist.

Typical of Mr. Segarini, the Motörhead incident was the act of a free spirt operating in the moment. “It just happened, and I let it,” he said recently on the podcast Toronto Mike’d. “I’m not one of those people who puts a lot of thought into spontaneity.”

After CHUM, Mr. Segarini landed his first of multiple gigs at the rival station Q107, which he left for a producer’s job at the new music-video station MuchMusic. He found the job boring, and was transferred to Toronto’s CITY-TV, where he was handed the reins to the all-night Late, Great Movies in the mid-1980s.

“He and his little gang of helpers seized control of the station and ran it with hijinks through the night,” said CITY-TV co-founder Moses Znaimer. “He seemed willing to do it for very little money, but, ultimately, he went too far.”

Mr. Segarini was relieved of his duties after multiple warnings and incidents involving yogurt, a cat and a rude gesture. Mr. Segarini later recalled a “4 a.m. confrontation that shouldn’t have happened, ended up with me being angry and escalating a misunderstanding into a standoff that resulted in me not coming back to work the next day.”

Mr. Znaimer could not recall the final caper, but did say that Mr. Segarini “lived the musician’s lifestyle,” which was true enough.

Born in San Francisco on Aug. 28, 1945, Robert Joseph Segarini was adopted six months later by grocer Giovanni Segarini and Mercedes Segarini (née Walters), of Stockton, Calif. They had turned to adoption after eight unsuccessful pregnancies.

Mr. Segarini said his parents gave him much love, a crib and a bedside Emerson table radio, “which was the only thing that could shut me up and lull me to sleep.” His mother sent two birthday cards to her son (one for his birthdate, and another for his adoption date) every year until her death in 1997.

As a child, he tap-danced at county fairs and, later, impressed friends and family with after-dinner performances of Lady of Spain on an accordion almost as big as he was.

He joined or formed regional bands including the Ratz (with Gary Duncan, later with Quicksilver Messenger Service) and the Us (who recorded two songs that were engineered by Sly Stone but not released because Mr. Segarini would not allow strings to be overdubbed onto them).

By his early 20s he had enthusiastically embraced the drug culture of the era. “I’d take a number-five horse capsule of real mescaline and put it in a glass of root beer, drink it and spend the next nine hours looking for god in a three-way G.E. bulb,” he recounted in Dave Bidini’s book On a Cold Road. “I spent the entire year of 1968 on acid.”

Mr. Segarini’s year of living psychedelically coincided with the release of Miss Butters, the first and only album by the San Francisco-based band the Family Tree. The imaginatively orchestrated conceptual work was mostly written by Mr. Segarini, who seemed to be lobbying for conscription into Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The cult classic later popped up at No. 27 on Elton John’s list of his favourite 100 albums he provided for Creem magazine in 1974.

After the Family Tree splintered, Mr. Segarini moved to Los Angeles and formed the band Roxy with singer-songwriter Randy Bishop. They released one eponymous album on Elektra in 1969. His next band, the Wackers, also signed to Elektra, released three albums.

Mr. Segarini had some success on his own in Canada, but never made it big. His 1978 debut solo album Gotta Have Pop was a witty, well-received tribute to the spirit of the music of his formative years. “That record was his statement against the bloated excess of the mid-1970s,” Mr. Mackowycz said. “He was planting a flag for the return of fun, accessible power pop.”

His music career wound down at the turn of the 1980s, when he found himself without a recording contract or a band for the first time since 1961. His transition to radio and television was unplanned. “I answered the phone one morning, hung up on the caller because I thought it was a prank,” he said. The caller, from CHUM-FM, phoned again and kept Mr. Segarini on the line long enough to offer him a job.

After leaving CITY-TV and Late, Great Movies, he turned to drugs. An extended binge in his 40s cost him his home, career, health and marriage, to Cheryl Byland Martin. “I spent 10 years down the rabbit hole,” he recalled, after straightening himself out.

One of Mr. Segarini’s most popular compositions is Rock and Roll Circus, recorded by both the Wackers and Roxy. “Run away to the rock and roll circus, and leave all your troubles behind,” the chorus goes. In his last few years, Mr. Segarini struggled physically and financially. The circus had left him behind.

“I got the feeling that Bob was unhappy at the end,” said his friend, the retired music promoter and publicist Richard Flohil. “I felt something was missing. What was missing was the good old days, and they were well gone.”

He leaves his daughter, Amy Mech; and grandchildren, Marshall Mech and Matilda Mech.

Brad Wheeler

Brad Wheeler