Stephen Smith, then-acting detective-sergeant in the cold case unit, at Toronto Police Headquarters on Sept. 19, 2022.Tijana Martin/The Globe and Mail

A Northern Ontario man was convicted this week of murdering two women 40 years ago, after police tracked him down with a new investigative technique that uses crime-scene DNA to close in on suspects by mapping their family trees.

The man, 62-year-old Joseph Sutherland of Moosonee, Ont., confessed after investigators demanded a sample of his blood for genetic testing, newly released court documents show.

Mr. Sutherland pleaded guilty on Thursday to the 1983 sexual assaults and killings of the two Toronto women, Susan Tice and Erin Gilmour. He was convicted of two counts of second-degree murder and will serve a life sentence, with no possibility of parole for 10 years.

Police arrived on Mr. Sutherland’s doorstep this past November after decades of stalled progress in their investigation of the deaths. They had used a technique known as investigative genetic genealogy to determine that DNA evidence left at the crime scenes by the killer had to belong either to Mr. Sutherland or one of his brothers.

Ms. Tice, a 45-year-old mother of four, had only recently moved to Toronto when she died. She was attacked inside her home on Aug. 16, 1983. Mr. Sutherland stabbed her 13 times, according to an agreed statement of facts filed with the Ontario Superior Court.

About four months later, the 22-year-old Ms. Gilmour, whose father was Barrick Gold co-founder David Gilmour, was alone in her second-floor Toronto apartment when Mr. Sutherland broke in, bound her hands and mouth and stabbed her twice in the chest, the statement says.

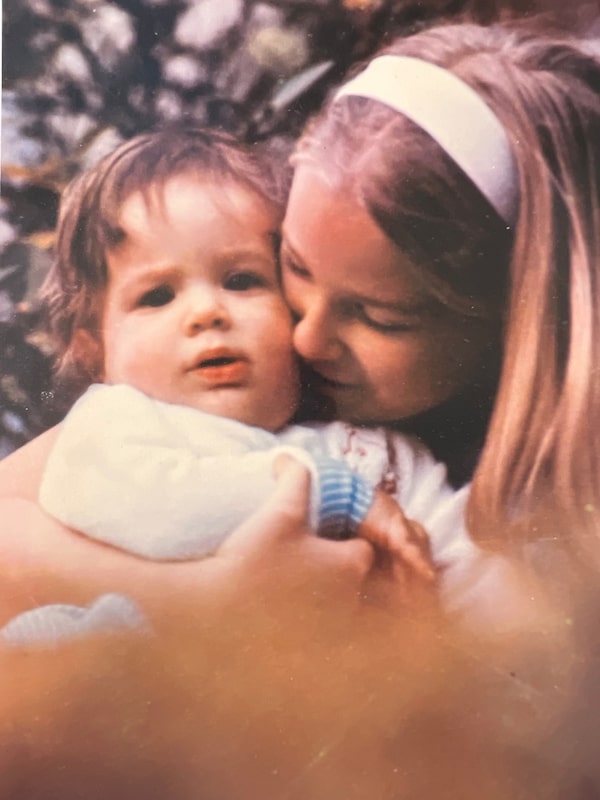

Erin Gilmour with her younger brother Sean.Handout

His biological material was recovered from Ms. Tice and Ms. Gilmour’s bodies, but police had no way of using it to determine his identity until recently.

By the early 2000s, police had access to some DNA analytical techniques. But an analysis at that time revealed only that the two women had been killed by the same man.

The investigation stalled until police gained access to genetic genealogy. The technique involves searching databases of genetic information controlled by private corporations. These businesses build their databases by encouraging individual customers of consumer genetic testing companies, such as Ancestry.com and 23andMe, to hand over their genealogical profiles for potential use in law enforcement searches.

By comparing crime-scene DNA to the genetic profiles in these databases, authorities can find people who may be relatives of the criminals they are seeking. This can help them make powerful deductions about the identities of suspects, even in cases from long ago.

In Mr. Sutherland’s case, the agreed statement of facts notes that Toronto Police started using genetic genealogy in 2021, and turned up five brothers whom they identified as potential suspects.

“A police investigation resulted in the elimination of four out of the five Sutherland brothers as the source of the crime scene DNA,” the agreed statement says. (It does not detail how the technology picked up on the Sutherland family, nor how police concluded Joseph was the guilty brother.)

Susan Tice.Courtesy of Toronto Police Service

Although critics fear genetic genealogy may erode privacy, police are embracing the technique as an investigative tool.

Detective-Sergeant Stephen Smith, who led the probe into the 1983 murders for the Toronto Police Service cold-case squad, pointed out that smaller police forces sometimes lack the resources to use the new technology.

“We’re lucky in Toronto, because we’ve had the resources and we have a cold-case unit that actually goes back and looks at these cases,” he said. “But a lot of services don’t have cold-case units. So people are kind of working on the corner of their desk with any historical offences.”

Det. Smith said Toronto Police Service policy is to retain crime-scene DNA evidence for decades. ”Anything unsolved,” he said, “we keep for 100 years minimum.”

Mr. Sutherland will appear in court in December for a sentencing hearing. He had originally been charged with two counts of first-degree murder, which carries a minimum penalty of 25 years without parole.

“We were happy to have reached this conclusion,” Ms. Gilmour’s brother Sean McCowan said of the guilty plea. “This wouldn’t have been possible five or 10 years ago.”

Several Ontario killers have been identified using genetic genealogy in the past three years, including a North Bay-area man who was convicted of a 1980s homicide and a Sudbury man who was convicted of a 1990s killing.

In 2020, Det. Smith announced that police had used genetic genealogy to find a man responsible for a notorious child slaying, the 1984 murder of nine-year-old Christine Jessop. The man had died by the time police identified him.

Ontario Privacy Commissioner Patricia Kosseim held a conference last month during which she highlighted the privacy trade-offs inherent in investigative genetic genealogy.

She said in a statement on Friday that the technology has brought “long-needed resolution for the families of victims.”

But she added that law enforcement agencies must be transparent in their use of the technique, “and be held accountable for decisions and actions that may affect the privacy rights of law-abiding citizens.”

Colin Freeze

Colin Freeze