NDP MP Blake Desjarlais, a 27-year-old Métis man, will be representing Edmonton Griesbach when Parliament resumes on Nov. 22.Jason Franson/The Globe and Mail

The man came outside, angry and yelling.

It was exactly the kind of situation Blake Desjarlais had feared. As an Indigenous man on the Prairies – and a relative of Colten Boushie – he knew all too well the peril of a brown man approaching a stranger’s door.

But Mr. Desjarlais walked up to the man, and they talked. Because Mr. Desjarlais, too, had known poverty and the deep toll it takes. Mr. Desjarlais, too, knew what it was like to not be able to afford food. And everything changed.

Mr. Desjarlais was, at the time, going door to door as a federal NDP candidate in what many believed to be an unwinnable campaign in the riding of Edmonton Griesbach.

Janis Irwin, now an extremely popular NDP MLA, had tried to take the riding in 2015, losing by a margin of about 3,000 votes despite two years of intensive campaigning and deep community connections.

Prominent social activist Mark Cherrington had lost by an exponentially larger margin after his run in 2019, in what appeared to be a sign of a widening Conservative advantage.

Going into the 2021 election, two-time Conservative incumbent Kerry Diotte – who once made headlines for tweeting a “Liberal Buzz Word” bingo card that included the words “first nations” and “indigenous,” and on another occasion posted a photo of himself with then-Rebel reporter Faith Goldy, thanking her for “Making the Media Great Again”– appeared to have a strong grip on the seat.

And here came Mr. Desjarlais, 27 years old, Métis, dark-skinned, two-spirit, with no previous experience in government. Not a lifelong New Democrat but, as he described himself, a guy who came from the bush, moved to the city and got educated because he wanted to help people.

It was a long shot, but for Mr. Desjarlais the chance felt like a gift, and he vowed to do everything he could with it.

“I felt I needed to give back to the people who gave me something. And what they’d given me, I believe, was the opportunity to be seen and the opportunity to have a voice,” he says. “And I wanted to give that back and make sure they had the opportunity to have a voice, too.”

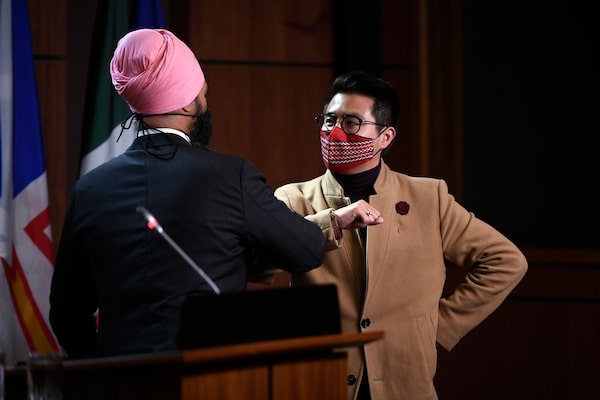

From Edmonton to Ottawa: At top, Mr. Desjarlais and NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh listen to elder Tom Durocher on Aug. 19, and at bottom, the men bump elbows on Parliament Hill after a news conference on the New Democrats' first caucus meeting.Paul Chiasson and Justin Tang/The Canadian Press

Mr. Desjarlais had been working with the Métis Settlements General Council, setting up a national office in Ottawa and working to negotiate agreements around Métis rights with the Liberal government, when he began considering the possibility of running for the NDP early in 2021.

It was his young nieces and nephews who persuaded him. They were so excited and proud, saying, “It’s gonna be so cool, uncle, having a Métis person. You’ve got to do this.”

Mr. Desjarlais – who earlier in his life sometimes said he was Chinese “just so I didn’t have to bring up the conversation as how I’m a ‘half-breed’ ” – was struck by their courage and pride.

“They inspired me to do it because I knew the potential effect it would have on them,” he says. “If I were in their shoes I’d be so proud, and I’d never feel ashamed of who I was or where I came from.”

Edmonton Griesbach covers a broad and diverse area of central Edmonton just north of downtown, and counts the largest urban Indigenous population in Canada outside Winnipeg among its residents.

Mr. Desjarlais’s birth mother, Brenda, struggled with addiction and was a sex-trade worker who worked on 118th Avenue, the artery of Edmonton’s own epidemic of missing and murdered women, and the place where Mr. Desjarlais’s campaign office would be located.

“I’m part of the story that is Canada,” Mr. Desjarlais says. “This doesn’t happen because of the individual will of one person. This happens because the state, Canada, has constructed this reality that they really wanted Indigenous people to not exist. That’s the plain, flat truth. They didn’t want them to exist, and created these mechanisms that we’re still reeling from today, and are still existing today.”

When Child and Family Services tried to seize him after his birth, his mother’s sister, Grace Desjarlais, stepped in and fought for custody. The sisters’ own family had been torn apart by the Sixties Scoop, and Grace – who only avoided being taken into custody by running away – was orphaned at seven years old.

Though she had only a Grade 3 education and limited means, Grace dedicated herself to reuniting Indigenous families, including her own.

She and her husband were able to get custody of Mr. Desjarlais and became his parents, he one of eight children they would raise in the Fishing Lake Métis Settlement near the Saskatchewan border, about three hours northeast of Edmonton.

It wasn’t always an easy life. Mr. Desjarlais’s father died when he was 12, and the family struggled with severe poverty. One of Mr. Desjarlais’s sisters went missing, and was later found dead on the streets in Vancouver.

“People think of these things as almost separate, like Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women or the CFS system or success stories, but they’re all the same story,” Mr. Desjarlais says. “There’s not one Indigenous person who hasn’t been affected by this.”

Mr. Desjarlais says anti-Indigenous prejudices 'broke my heart' when he arrived in Edmonton to study.Jason Franson/The Globe and Mail

Moving to Edmonton for university, Mr. Desjarlais discovered what he describes as “this huge hate for Indigenous people, especially queer people.”

On one occasion, three men came to his door threatening to kill him. At a party in university, he watched two white men he thought were friends stand by as another man made racist comments and violent threats against him.

“They wouldn’t look at me, so they knew what was happening was wrong but were willing to accept that reality,” he says. “And that broke my heart, and that made me lose a lot of faith. It made me very frustrated, made me angry at the world and made me think, maybe it is better that Indians go away because maybe they wouldn’t have this anger in their hearts.”

He says at some points he was too scared to go to class, afraid to even leave his apartment. He knew he couldn’t stay in that situation, and applied to the University of Victoria after learning about First Peoples House, a supportive community especially for Indigenous students.

There, Mr. Desjarlais was transformed. He studied Indigenous issues and political science and got his degree, then accepted a position with the Métis Settlements General Council and moved back to Edmonton, to help his people at home.

“At that point, I was strong enough,” he says. “I was a totally different person, I wasn’t this really broken, scared, half-scholar any more. I was like this fully fledged, Indigenous, proud person.”

Mr. Desjarlais speaks with nurse Samantha Waller at the East Edmonton Health Centre on Sept. 18.Candace Elliott/Reuters

Mr. Desjarlais’s campaign team immediately recognized the power that lay in his ability to connect with people. He was set up with Ashley Ogilvie, who had worked on several other NDP campaigns in the city and was known as a dogged and enthusiastic door-knocker.

When Mr. Desjarlais worried about his safety going door to door, Ms. Ogilvie promised she would use all her privilege as a white, blond woman to protect him no matter what, and she meant it. When they crossed a street, she always walked in front, knowing cars would stop for her.

Together, they set out to knock on every door in the riding, trying to meet as many people as possible and find out what mattered to them, regardless of whether they would vote for him. They went to every home they could, and to those who didn’t have homes at all.

These were communities Mr. Desjarlais had grown up with, tough times he’d lived himself. He had worked in oil and gas, experienced racism, lived in poverty, lost people to violence and addiction, understood – and lived – many of the social issues facing those he met.

But while Mr. Desjarlais had known hardship, he also knew the things that helped him and his family – in particular, the power of community. Sometimes he would look out at 118th Avenue and think about how he would not have existed if it wasn’t for those who helped Brenda survive. He thought about how, even when his family didn’t have enough money for food, they never went hungry.

“It’s literally neighbours, people who are also poor, giving to these people, and I know what that feels like. I know exactly what that feels like,” he said. “When my dad died, we had nothing. No money, just nothing. People coming over with a dish for suppertime, knowing we didn’t have money for food, they gave us that.”

Mr. Desjarlais and Mr. Singh stop for selfies with supporters in Edmonton on Aug. 19.Paul Chiasson/The Canadian Press

In their months of campaigning – eight hours a day, every day, including during a record-breaking heat wave when they did too much and got heatstroke – Ms. Ogilvie watched Mr. Desjarlais de-escalate situations, withstand racist encounters and completely turn around people who wouldn’t have expected to like or agree with him. She saw him persuade people who had never voted before – some of whom did not know how to vote – to cast a ballot.

She also saw the reactions in the families they met, how some of the kids, especially the Indigenous ones, looked at him. She knew the stakes were incredibly high. It would mean so much to those children if he was elected, and be equally meaningful if he wasn’t.

During the campaign, Mr. Desjarlais’s older sister, Skye Durocher, would sometimes drive in three hours to support him for a couple of hours, then drive home again.

“There’s all these barriers that are put in place to keep Indigenous people in their communities, and to keep them in unemployment and low education level,” she says. “So for people to see this young person who has been through all these barriers, barriers of poverty, all these things, and to still come out on top – that’s amazing. Even if he didn’t win, I think people would be still so proud of him.”

Mr. Desjarlais won the riding, beating Mr. Diotte by 1,468 votes, a close enough race that Mr. Desjarlais and his team waited until the advance ballots were counted before accepting the victory. Weeks later, Ms. Ogilvie still gets emotional when she thinks about it.

“Really, where my mind went was to those families, and particularly those children and the young people who would look at him and think, ‘That’s my representative,’ ” Ms. Ogilvie says. “When they talk about our MPs in school, they’re going to talk about him.”

Mr. Desjarlais says he will be thinking of Métis leaders like his great-grandfather when he takes his seat in Parliament, he told The Globe at a bookstore and coffee shop in his riding.Jason Franson/The Globe and Mail

Thinking about how he would tell his own story, Mr. Desjarlais said it would be about not only what he endured, but how he survived it. He sees and collects these survival stories for himself, and he knows the power of them. He thinks about what he has learned from Grace’s life, from books such as Jesse Thistle’s From the Ashes, from the elders he worked with at university in B.C.

“They really taught me to be brave and to acknowledge where I’ve come from, because those stories, the sad stories, are actually strength in disguise,” he says. “And they taught me how to use that strength, because they themselves were strong because of it.” He says he hopes that his story can do that for people, that his very life is proof an Indigenous person can survive the system, and that it can get better.

Mr. Desjarlais was sitting at Mandolin Books & Coffee Company, a small business in his riding. He wore a camel-coloured coat and aubergine turtleneck. His face was framed by round black glasses, punctuated with a black mustache and goatee. Outside, the first storm of the winter was blowing in. It was Métis Week, 135 years less one day after Métis leader Louis Riel was executed for treason.

While there have been about 20 MPs since then who identify as Métis, there have been none, Mr. Desjarlais says, that directly come from “the fight,” the continuing battle by Métis leaders for Métis rights and recognition.

Mr. Desjarlais says that when he takes his seat for the first time, he will be thinking of those Métis leaders, including his great-grandfather, Pierre Poitras, who seconded the Manitoba Act and was captured and beaten for supporting Riel and the Métis resistance. Another great-grandfather, François Dauphinais, also served on Riel’s provisional government.

“These are the people I come from. People call them traitor. People call them all these terrible things. But to me, it’s like giving them what was always theirs,” he says. “ … Even Louis Riel himself thought the Métis people would sleep for 100 years before we’d ever have a chance. It’s been over 100 years since his execution, but he was right. We would survive. It’s like almost fulfilling a prophecy.”

Mr. Singh addresses his caucus on Oct. 6.Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press

Mr. Desjarlais will be Canada’s first two-spirit MP, and Alberta’s only Indigenous member. He is one of 12 Indigenous MPs out of 338 total in Parliament.

His sister, Ms. Durocher, says she worries about him in Ottawa, but that she knows that he would face racism and prejudice anyway. “It’s just now he has a spotlight,” she says. “Now he has a platform.”

Whenever he can, Mr. Desjarlais likes to go into the bush to fish or hunt, returning to the things he learned from his father, profound truths he carries with him. That it’s not that bad. Nothing’s ever too hard. Nothing’s ever too much.

When Mr. Desjarlais told Grace he was elected, she wasn’t surprised at all. He recalls her saying, “Well, that’s good. Anyway, are you going to come by the house and chop wood? Because we need wood. Winter’s coming.”

It was comforting, grounding to know that, while some things in his life are about to change profoundly, others will not. New seasons will come. There will be wood to chop at home in Fishing Lake.

He says Grace always told him, “Just try. If you just survive, that’s a lot. If you survive it, you did it.”

Jason Franson/The Canadian Press

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Jana G. Pruden

Jana G. Pruden