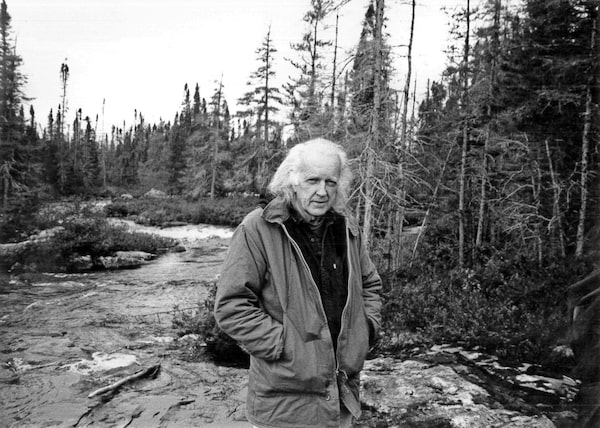

Author, filmmaker and journalist Boyce Richardson in 1990.Tamarack Productions

Boyce Richardson, an author, filmmaker and journalist who was considered a giant of his profession for his work investigating complex Indigenous issues in an era when such stories were usually ignored, died in Montreal at Jewish General Hospital on March 7. He was 91, two weeks removed from his 92nd birthday.

First as a newspaper reporter and then as a filmmaker and author, Mr. Richardson dug into the story of the James Bay Crees. Through his work, including the documentary films Job’s Garden, Cree Hunters of Mistassini, Our Land is Our Life and Flooding Job’s Garden and the books Strangers Devour The Land and People of Terra Nullius: Betrayal and Rebirth in Aboriginal Canada, he contributed mightily to the understanding of Canada’s Indigenous communities.

Mr. Richardson was a storyteller whose work was marked by exceptional clarity and elegance of expression. An advocate for social justice, he practised reconciliation decades before it became a Canadian buzzword.

Boyce Richardson was born March 21, 1928, in Wyndham, Southland, New Zealand, to Robert and Letitia Richardson. As a young print journalist in his early 20s, Mr. Richardson departed New Zealand, travelling first to Australia then to India and the United Kingdom. He was keen to see the world and to transcend his strict Protestant family background, according to his son, Robert Richardson, a lawyer. “[His parents] didn’t think much of him being a writer. They thought one day he would get a real job.”

Mr. Richardson set out in 1950 with his wife, Shirley, a woman of Maori descent whose father was a trade union activist. The couple were socialists. “They felt there was a better way for us to live than raw capitalism,” Robert said.

It was in Canada, his adopted country, where he arrived in 1954, that he made his mark working as journalist in Northern Ontario and Winnipeg before joining The Montreal Star. In the 1970s, Mr. Richardson began a profound study of the Crees of James Bay in Northern Quebec as Hydro-Québec launched its “project of the century” of dam construction and massive flooding to create reservoirs.

“Boyce was a trailblazer. He was a voice in the wilderness as one of the few mainstream journalists interested in Indigenous issues at that time," said Harvey McCue, a semi-retired Anishinaabe consultant on First Nations topics, former director of education services for the James Bay Cree and co-founder of Indigenous Studies at Trent University.

As a young man, Dr. Philip Awashish, an eventual signatory to the 1975 James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement that partially settled the furor over Hydro-Québec’s plans, worked with Mr. Richardson, introducing him to Cree chiefs and hunters and acting as a translator. “I knew him to be passionate, tenacious and loyal in matters pertaining to the pursuit and achievement of social and legal justice for Aboriginal people,“ Dr. Awashish wrote of his colleague in Nation Magazine, a news service for the Crees of James Bay.

Mr. Richardson’s work educated academics and activists. John Wadland, professor emeritus of Canadian Studies at Trent University, says he was “blown away” by the film Cree Hunters of Mistassini. Mr. Wadland used it in his courses for two decades. “I can’t think of anything that moved me more as a young academic. I was absolutely gobsmacked. It is a magnificent exploration of Indigenous community. His work opened a door for me and others.”

Mr. Richardson cut quite a figure in his heyday at The Montreal Star. Mr. McCue remembers their first meeting at an Indian-Eskimo Association of Canada meeting in 1970. “In walked Boyce, dressed entirely in black leather. He sat and glowered for the entire meeting. That was the last I saw of him until 1988, when suddenly we were neighbours in Ottawa. I reminded him of that encounter. We laughed and he said, ‘how embarrassing.’”

In the early 1970s in Cree territory, Mr. Richardson partnered with National Film Board director and cameraman Tony Ianzelo and producer Colin Low. Mr. Ianzelo believes that the methodology they worked out in the bush of Northern Quebec served them well. “Boyce would say, ‘Look I’m a journalist. I know nothing about filmmaking.’ I rather enjoyed that. I only wanted to film. I said, ‘Okay, Boyce, keep digging and then we’ll talk about how to visualize it.’”

Mr. Richardson would set out with his notepad, and accompanying translator when required, ask a multitude of questions and then confer with Mr. Ianzelo about the next filming session. “We’d meet in the morning. He often had a list of ideas or things that people had said that interested him. We’d then figure out how to film it.”

In 1978, the duo plus producer Tom Daly turned out three films based on a stay of about three months in China. North China Factory looks at the organization and discipline of workers at a textile mill in Shijiazhuang. Whether in a Chinese factory or Cree bush camp, Mr. Richardson and Mr. Ianzelo paid meticulous, respectful attention to ordinary people. Mr. Richardson "was not an elitist in any sense. He had little time for politicians or blowhards. He was always for the worker,” Mr. Ianzelo said.

Mr. Richardson remained committed to Indigenous issues in Canada for many years. Russell Diabo, a Mohawk policy analyst and activist, introduced him to the Algonquin community at Barriere Lake, Que. That resulted in the 1990 film Blockade: Algonquins Defend the Forest. The duo also collaborated in developing the book Drumbeat - Anger and Renewal in Indian Country, edited by Mr. Richardson, in which Indigenous leaders from across the country documented their struggles.

“He had a sensitivity that most mainstream journalists don’t have," Mr. Diabo said. "When he saw an injustice, he was indignant.”

After his wife’s death, Mr. Richardson moved back to Montreal in 2012. Mr. Diabo would take his old friend out for dinner there, “One time, I saw him eat a whole leg of lamb. He was from New Zealand, eh.”

His son Robert also recalls his audacious eating habits, remembering that Mr. Richardson was extremely proud that he once won an oyster-eating contest in Winnipeg. He ate 120 of them.

Mr. Diabo last spoke to Mr. Richardson in January. “We talked about the Wet’suwet’en situation. He was very angry.” In the penultimate post of Mr. Richardson’s blog, titled BOYCE’SPAPER, he wrote, "Well, all I can say, looking back 52 years to when I first looked into the lives of Canada’s Indigenous people, is that although the publicity accorded them today is immensely greater than then (when they were hardly mentioned in the press) but that in many essential ways things have not changed that much.”

Boyce and Shirley Richardson had a rich family life with their four children.

Paula Madden is mother to their only grandchild. Originally from Jamaica, she got to know Mr. Richardson’s work as a young adult when she returned to university. She believes that his output is as important today as ever. “He provided space for Indigenous people to tell their stories in their own voices,” says Ms. Madden, an adult educator in Clyde River, Nunavut. “Knowing how to move about this space where I now live in a respectful way is perhaps Boyce’s greatest gift to me.”

Mr. McCue believes that the journalist he met in the 1970s mellowed. Mr. Richardson would stop to chat as he passed by his neighbour’s house. The two compared notes about goings on in James Bay Cree communities, “we were kind of soulmates in that regard.” Mr. Richardson was also keenly interested in the career of Mr. McCue’s’s son Duncan, a CBC journalist. “He was still passionate in his views, but when we met as I was shovelling snow or raking leaves, he struck me as gentle and peaceful.”

Mr. Ianzelo last saw Mr. Richardson two days before his death. The friend he had known for half a century as a great cricketer, cyclist and walker was now confined to a hospital bed. “Boyce knew it was coming. … He said, ‘What the hell, I had 90 or so years, we had four great kids and I’ve done what I liked to do.’ ”

Mr. Richardson leaves his children, Ben, Robert, Thom, Belle, and grandson, Ngozi.