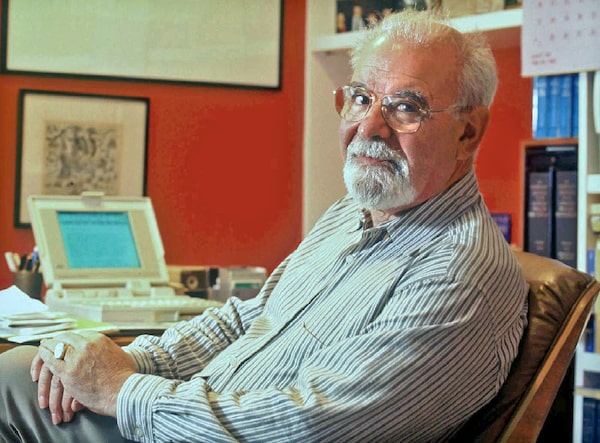

Dr. Vivian Rakoff, seen here on Aug. 24, 1997, is remembered for his extraordinary intellect, kindness, sense of wonder and the agility with which he wove together ideas from a vast range of disciplines.John Lehmann/The Canadian Press

It has been nearly 20 years, but the words of esteemed Toronto psychiatrist Vivian Rakoff still ring out clearly in Aristotle Voineskos’s memory.

“I will not tolerate the distinction between psychology and biology. Every thought is a neural event," Dr. Voineskos, the incoming vice-president of research at Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), recalls his mentor saying.

With this statement, the senior professor staked his position in a long-standing and ongoing disagreement over “the soul of psychiatry,” Dr. Voineskos explained.

“There’s still these sort of artificial dualities between psychology and biology, the brain and the mind,” he said. “Vivian was sophisticated enough to understand that there’s no such divide, that these things are integrated and they’re really similar representations of the same thing.”

Dr. Rakoff, a past chair of the University of Toronto’s department of psychiatry, psychiatrist-in-chief at the former Clarke Institute of Psychiatry and member of the Order of Canada, died Oct. 1 in his home in Toronto at the age of 92. He had Parkinson’s disease.

To the many he inspired, he is remembered for his extraordinary intellect, kindness, sense of wonder and the agility with which he wove together ideas from a vast range of disciplines, from classic literature and philosophy to politics and pop culture. If every thought is a neural event, then Dr. Rakoff’s brain composed complex neural symphonies.

At a time when many people are divided and entrenched in their own viewpoints, Dr. Rakoff’s open-mindedness and willingness to engage in reasoned discussion are qualities the world needs now more than ever, Dr. Voineskos said.

“That way of thinking, that ability to tolerate complexity and uncertainty and multiple viewpoints concurrently, I think, is not just important for the future of psychiatry, it’s important for the future of science and the advancement of humanity,” he said.

Vivian Morris Rakoff was born on April 28, 1928, in Port Nolloth, a small fishing town on the west coast of South Africa. He was the second of four children to David and Bertha Rakoff. His father, who had emigrated with his family at age 10 from Belarus, worked to earn a living from a young age and eventually became a successful businessman, operating a wholesale and retail store, liquor store and hotel in the small town. His mother, who hailed from Chicago, once told her daughter-in-law she had never needed to work a day in her life.

Vivian was the intellectual star of his family, his wife, physician Gina Shochat-Rakoff, said. He learned to read at an exceptionally young age, and followed his older brother to school, only to be turned away because he was too young.

When he was about five years old, he and his mother and siblings moved to Cape Town, where he was able to attend good schools. He read every book he could get his hands on and devoured his brother’s set of encyclopedias. With an eidetic memory and a love of poetry and the arts, he often acted in school performances and had a knack for reciting entire plays. Until the week before his death, he was able to recite the works of Shakespeare, Yeats, Wordsworth, Keats and Eliot, his daughter Ruth Rakoff said. He wrote numerous poems, plays and essays throughout his life, and in his later years, gave lectures on the plays performed at the Stratford Festival.

After receiving a bachelor of arts degree in Cape Town, he had intended to attend Oxford University or Cambridge University. But instead, he took a year-long break from his academic studies in 1948 and travelled to Palestine, where he witnessed the establishment of the state of Israel and worked on a kibbutz.

Upon his return to Cape Town, he earned a master’s degree in psychology, then went on to medical school in London. His decision to enter medicine arose from a chance encounter with an acquaintance on the street, Dr. Shochat-Rakoff said.

When he learned his acquaintance was now pursuing medicine, "he said, ‘Oh, good idea,' and went and registered for medicine,” she said. “He did not grow up thinking of himself as a physician.”

After eight years in England, he returned to South Africa where he began his psychiatric training at the University of Cape Town. This field suited his compassion for others and his pioneering spirit.

“After all, there are no new bones in the foot since the first textbooks were published, but the frontier of the mind was ripe with unexplored territory for a curious intellect,” his son Simon Rakoff wrote in his eulogy.

In 1959, through family friends, he met Gina Shochat, who was then an intern in Port Elizabeth, South Africa. The two married six months later.

The couple, along with their eldest child, Simon, at eight months old, boarded a cargo boat with their meagre belongings in 1961, and arrived in Montreal after an 18-day journey at sea. Dr. Shochat-Rakoff said their departure was motivated by their desire to leave the politics and racism of South Africa. In Montreal, where the couple’s two other children, Ruth and David, were born, Dr. Rakoff completed his psychiatric training at McGill University.

Their early years in Canada were lean, as the couple had little money and Dr. Shochat-Rakoff, a general practitioner, was not permitted to write the exams for her credentials to practise medicine in Canada until she became a citizen. Nevertheless, they made new friends quickly and soon had a social circle.

Simon and Ruth recall a childhood home in which witty banter was a competitive sport and the mantra was “Let’s look it up.” It was common to witness their father laughing at juvenile jokes, while their mother shook her head.

“He never heard the word shampoo without giggling and saying, ‘I prefer the real thing,’” Simon wrote, noting that in his later years, his father would ask to be taken to see the Berczy Park dog fountain on Toronto’s Wellington Street during their lunch outings together. “Its whimsy and humour made him smile.”

While in Montreal, Dr. Rakoff and his colleagues published one of the first articles on intergenerational trauma in 1966, after observing the high percentage of children of Holocaust survivors in the clinical population. However, he stopped pursuing this area of research soon after, owing to opposition from survivors who didn’t want their children pathologized, which was not his intention, Dr. Shochat-Rakoff said. Today, intergenerational trauma is a widely studied phenomenon.

In 1968, the family moved to Toronto. From 1980 to 1990, Dr. Rakoff served as chair of the department of psychiatry at the University of Toronto and psychiatrist-in-chief at the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry, a psychiatric hospital that later amalgamated into what is now CAMH.

In 1992, he opened the Vivian Rakoff Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Centre, bringing Canada’s first PET centre devoted to imaging research into mental illness to the Clarke Institute.

“It’s important to bear in mind he was not an imaging researcher. This didn’t meet some selfish need to surround himself with equipment he was going to use. It was much more high-minded than that,” said David Goldbloom, senior medical adviser at CAMH. By doing so, he put the Clarke Institute “on the map globally as one of the world’s leading research imaging centres in psychiatry.”

In 1997, Dr. Rakoff inadvertently found himself in a media maelstrom, after a private memo he wrote for his friend Liberal MP John Godfrey about his impressions of then-Quebec premier Lucien Bouchard was made public. In a response, published in The Globe and Mail, Dr. Rakoff emphasized that his speculations about Mr. Bouchard’s character, which deputy premier Bernard Landry decried as “pseudo-scientific mockery," were not a psychiatric report.

“My document obviously took on a life of its own, but if it generates so much demonizing passion, it should at least be read,” he wrote. “It takes only 10 minutes without moving the lips.”

As a polymath and dazzling speaker, Dr. Rakoff was “a vanishing breed,” Dr. Goldbloom said.

Ultimately, his multi-dimensional perspective gave him a better understanding of the patients he sought to help, said Roger McIntyre, a professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto.

“It made him a better physician, in my view, because I still believe despite all the technology we have and all the exciting advances in science… the role of the physician, still to this day, is to bring relief to people’s suffering,” Dr. McIntyre said. “He had an uncanny ability to express his empathy in a way that was so sincere, in a way that was so connecting, that it was so alleviating of distress, so alleviating of dysphoria or disaffection.”

Dr. Rakoff leaves his wife, Gina Shochat-Rakoff; children Simon and Ruth; grandchildren, Micah, Amit, Asaf and Zoe; and his sister, Riva Levick. He was predeceased by his son David Rakoff, an acclaimed writer who was known for his books of essays, including award-winning Half Empty, and his regular appearances on This American Life. David died of cancer in 2012 at the age of 47.

Wency Leung

Wency Leung