Trish McAlaster

Early one summer morning, in July of 2017, Pat McCarthy was doing his rounds of Davisville Junior Public School – garbage bag in one hand, trash-picker in the other – when he found a man, curled into the corner of a cement-floored breezeway next to the kindergarten playground, asleep.

The caretaker went about his business. When he checked back, the man was gone. But the next morning, he was back. And the next.

By the time school resumed in September, the two men were in the habit of wishing each other good morning as one packed up his sleeping bag and went on his way, into the leafy mid-town neighbourhood that my children and I have called home since moving in with my mother seven years ago.

“He was clean-cut and polite,” Mr. McCarthy recalls, adding, with evident concern, “and pretty young.”

Mr. McCarthy and the principal, Shona Farrelly, agreed there was no need to evict the man, who was invariably gone without a trace before students arrived. Their view was not shared by the Toronto District School Board security guards who discovered him on a night check and told him to clear out. But when he resurfaced on the playground some days later, Mr. McCarthy told him he could stay, and asked security to leave him alone. And so the man – we’ll call him Bernie – became a fixture at the school. Not for the first time.

Arriving early one morning, Ms. Farrelly introduced herself and the man told her that he was a former student. He’d always liked the school; it felt safe and familiar, especially now, when he was down on his luck and saving up for rent. He promised to respect the unwritten rule: no overlap with students.

Ms. Farrelly told Bernie he could leave his sleeping bag on the playground. Mr McCarthy provided a large plastic bin for him to store his things.

The kindergarten classes that used the playground daily were quick to notice these additions. Ms. Farrelly explained that they belonged to a friend of the school who needed a place to sleep. At recess, a crew of kindergartners lugged a large wooden dollhouse over to Bernie’s corner and positioned it in front, as a privacy barrier. Nobody was allowed past it.

Bernie slept there all year, through a winter in which the city issued 31 extreme cold weather alerts and had to open provisional warming respites and the Moss Park Armoury to accommodate overflow from the existing shelter system. When school was in session, Bernie was gone before students arrived, always leaving his sleeping bag neatly rolled in the corner; during the holidays, he slept longer.

Every Friday afternoon, Ms. Farrelly left a bag on Bernie’s bin containing whatever donations students, parents and staff had brought in over the week: socks, gift cards, packaged food, hand-warmers, money. Over the winter, Bernie’s holdings expanded to include a grey tarp and a new, thicker sleeping bag.

On a few frigid winter nights, my sons and I walked over the school to check on Bernie. My younger son was determined to meet him, to understand how this could happen. Sometimes Bernie’s sleeping bag was rolled up; sometimes, he was curled into the bottom of it, bathed in the red glow of a terrarium light from the classroom. Once, my seven-year-old burst spontaneously into O Canada, hoping for a response. There was none.

When Bernie attended Davisville in the 1980s, a three-bedroom house near the school cost an average of $166,000, a quaint-sounding sum today, equivalent to the total value of the cars parked in some driveways. In 2017, as rent increases hit a 15-year high, the rental vacancy rate hit a 16-year low. The waiting list for subsidized housing in this city currently stands at 200,000. “Affordability crisis” and Toronto have become virtually synonymous.

In February, the senior kindergarten class fashioned a mail box for Bernie out of cardboard and scraps of material. They collected pictures and messages for him from the entire school. Kaiden, 5, drew Bernie a house to live in. Its sole indoor feature was an orange fire roaring in a fireplace, connected to a diagonal chimney spewing curly black smoke.

“We can give him a house because we have money,” Kaiden explained. “We go skiing.”

In the spring, my sons and I saw Bernie’s thin legs sticking out of the sleeping bag. “What does he look like?” they asked, scouring the neighbourhood for someone that met Mr. McCarthy’s description. They fixated on the word “clean-cut.” Until Bernie, homelessness for them had had no face or name.

In June, Ms. Farrelly wrote in her weekly message to Bernie that the school was slated for demolition, starting in August. He wrote a note back, suggesting they meet. He wanted to thank her in person for all that the school had done.

At the local Tim Hortons, Bernie told the principal how he’d graduated high school in the 1990s, worked various jobs and managed to make rent. But gradually the city got ahead of him. He tried shelters and was robbed. Then he found his place, at Davisville. Now, he was working again, in roofing, and hoped that by summer’s end, he would have a place to live.

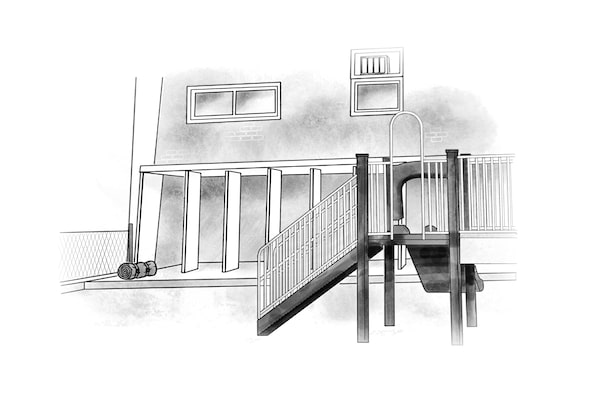

Today the school is surrounded by construction fencing. Once a showpiece of postwar Modernism, the building now looks like some kind of caged monster; electric cables dangle from its ceilings, windows are smashed, tarps patch some walls, like bandages.

Across the street, a massive crane swings bundles of steel bars across the foundation of a condo to be.

Among the woodchips of the kindergarten playground are empty cans, deflated balls and a lone toy excavator. Squirrels natter in a mulberry tree. All that remains of Bernie is his original sleeping bag, neatly rolled up, in the corner.

Special to The Globe and Mail