SUPPLIED

Investors and pundits caution inflation may soon soar for myriad reasons: governments’ fiscal spending, rising oil prices, increasing shipping costs—just to name a few. However, Fisher Investments Canada believes many misunderstand inflation and its drivers. In this article, we will define inflation, dispel some recent fears about inflation and discuss when the right time is to fear inflation.

Inflation, defined

Inflation is an increase in the general level of prices for goods and services throughout an economy over an extended period. Since inflation covers a broad array of goods and services, it can affect people differently, and your personal inflation experience will vary based on the goods and services you purchase often. Inflation’s broad scope can make it somewhat difficult to measure, but there are multiple indicators that try, including indexes that track certain baskets of goods and services to capture general trends in prices.

Whilst the true cause of inflation is somewhat complex and debated, Fisher Investments Canada shares Nobel Prize–winning economist Milton Friedman’s view that inflation is driven by too much money chasing too few goods and services. Based on that definition alone, it may seem reasonable that inflation is set to rise now—and it might! But we will discuss why we believe many of today’s inflation fears may be unfounded.

Addressing some recent inflation fears

1. Will supply-chain disruptions and increasing shipping costs cause inflation?

Supply shortages—like those in semiconductors and other products recently—can cause temporary price increases due to the “too few goods and services” part of the equation. However, shortages like these tend to be fleeting in nature. For example, the recent semiconductor shortage developed partly from a lack of production during the pandemic-related lockdowns and partly from rising demand for work-from-home equipment in the pandemic environment. However, these higher prices likely tell producers it’s time to invest in new production to meet demand, eventually helping to increase supply and bring prices back into balance.

Another fear is that shipping disruptions—like those caused by the stuck tanker in the Suez Canal earlier this year—will lead to higher shipping costs, causing inflation. However, these disruptions are often similarly temporary. They can cause backlogs of container ships and trucks, but companies and the shipping industry normally adapt to get around short-term issues like this one.

2. Are higher oil prices inflationary?

Technically, yes, because energy (meaning oil and gas) is a component in many broad inflation measures. However, many of these measures also offer “core” readings, which exclude things like oil and food, whose prices often fluctuate based on their individual market forces. Some people believe energy prices can leak into prices of other goods as businesses mark up their products to pay for rising energy costs. However, companies that use a lot of oil and gas often avoid having to raise their prices by hedging oil purchases with futures contracts. Whilst rising energy prices can influence some inflation measures, they aren’t really a primary driver of systemic inflation, and “core” measures can help investors see whether inflation is broad-based or tied to fluctuations in commodity prices.

3. Will COVID-related fiscal-relief packages stoke hot inflation?

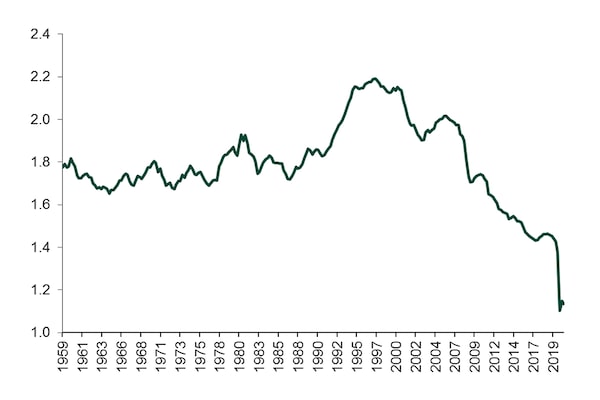

Following governments’ COVID fiscal-relief packages during the pandemic, some people feared governments were pumping too much money into their economies, which would overshoot potential economic output and stoke inflation. For example, in the U.S., whilst a significant portion of that U.S. relief package was in the form of checks to American families, they don’t necessarily translate immediately into higher spending and prices. People could just as easily use those funds to pay down debt or rebuild savings. The huge increase in America’s savings rate from 7.2% in December 2019 to 13.7% at 2020′s close suggests many people did just that last year.¹ To drive inflation, you need money chasing after goods and services—and, so far, that isn’t happening. To go back to the U.S. example, whilst U.S. money supply has risen some, M2 money velocity—a measure of how often money is changing hands—is still hovering near all-time lows. Such low velocity of money suggests the “chasing too few goods and services” part of the equation may not be present yet.

Exhibit: Velocity of M2 Money Supply Remains Low

Source: US Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, as of 09/04/2021. US M2 money velocity, quarterly, January 1959–October 2020.SUPPLIED

When investors should worry about inflation

Inflation isn’t inherently bad for equities, which have actually done quite well amidst rising inflation in the past. Inflation can be a risk to the equity market and economy—but it may not be in the way many people assume. Fisher Investments Canada believes the issue begins when central banks try to combat rising inflation by hiking short-term interest rates too high. Here’s how it works.

Generally, banks generate revenue from the interest they receive on new loans (often roughly reflecting long-term rates), whilst they pay interest on deposits (usually near short-term rates). Therefore, the difference between long- and short-term interest rates acts as a proxy for banks’ loan profitability. When long rates surpass short rates, banks are encouraged to make new loans, which can spur rising money supply and—crucially—how often that money is changing hands (aka the velocity of money). This process is often how systemic inflation begins.

But the real trouble usually stems from central banks reacting rashly to rising inflation. When this happens, central banks, in an effort to rein in inflation, may hike short-term interest rates above long-term rates. If short-term rates get too far above long-term rates and stay that way for a long time, it can reduce banks’ profits on new loans and discourage further lending. Lower lending, in turn, disrupts credit availability for businesses and consumers, ultimately hurting economic activity.

Whilst we don’t see signs of this happening soon, we believe central banks’ actions are inherently unpredictable and worth constant monitoring. Luckily, people are increasingly worried about rising inflation today. We believe that’s good because markets efficiently price all widely known information, thus removing any surprise power to move equities much. We believe the more people are watching and talking about inflation, the less likely it sneaks up and surprises investors and central bankers.

¹Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, as of 02/10/2021. Personal savings rate, December 2019–December 2020.

Fisher Asset Management, LLC does business under this name in Ontario and Newfoundland & Labrador. In all other provinces, Fisher Asset Management, LLC does business as Fisher Investments Canada and as Fisher Investments.

Investing in stock markets involves the risk of loss and there is no guarantee that all or any capital invested will be repaid. Past performance is no guarantee of future returns. International currency fluctuations may result in a higher or lower investment return. This document constitutes the general views of Fisher Investments Canada and should not be regarded as personalized investment or tax advice or as a representation of its performance or that of its clients. No assurances are made that Fisher Investments Canada will continue to hold these views, which may change at any time based on new information, analysis or reconsideration. In addition, no assurances are made regarding the accuracy of any forecast made herein. Not all past forecasts have been, nor future forecasts will be, as accurate as any contained herein.

This content was produced by Fisher Investments Canada. The Globe and Mail was not involved in its creation.