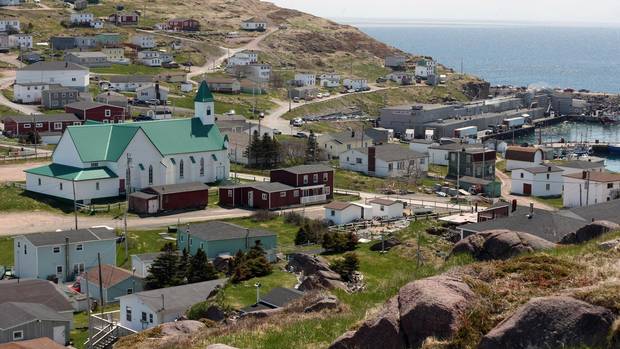

Cupids is a tiny Newfoundland village “around the bay” from St. John’s. In a nod to its English heritage, the Union Jack flapping on the shore across from the fish plant is the second-largest in the British Empire. It was here that John Guy settled the second English community in North America, here that the first English child was born in what is now Canada in 1613.Before Europeans settled in Newfoundland, the ships just followed the cod. Then it was brought ashore to be salted and dried in coastal villages founded for just that purpose. But history does repeat itself. Once again, fishing is mostly migratory, with countries sending massive factory-freezer trawlers around the world to harvest and process the catch at sea.

The long, low-slung fish-processing plant on the other side of Cupids Harbour used to employ 80 workers who processed cod caught in nearby waters. Today it employs six. Next to the building is a shed that now houses squid bait for catching snow crab. Last year, the squid came from Argentina. This year, it came from Japan.

In 1992, when federal Fisheries and Oceans minister John Crosbie came to Petty Harbour, another fishing village just south of St. John’s, to announce the cod moratorium, most people expected the fishing ban to last a couple of years. Twenty-three years on, they are still waiting for it to be lifted. Fished to commercial extinction, the cod stocks collapsed and put 30,000 Newfoundlanders out of work. Coastal villages emptied out.

Sometimes, it seems as if cod is all anyone talks about, inside the Cupids Legacy Centre and on the streets of St. John’s, where cab drivers and tattooed twentysomethings still talk about family fishing rights. So when scientists announce the cod is coming back, it’s big news. It rubs salt into old wounds throughout Atlantic Canada. And it raises questions: Can we get it right this time? If the moratorium is lifted, can we find a way to manage the fishery sustainably?

“It wasn’t just a job I had,” says Tony Doyle, a sixth-generation fisherman from Bay de Verde, north of St. John’s. “When we were sitting in the shade at a party, we were talking codfish. It consumed our community.” And their community consumed it. Cod’s spawning biomass dropped from 1.6 million tonnes in 1962 to a mere 110,000 tonnes in 1992.

We’ve been waiting decades for good news. And finally, we have some. Scientists are confirming what fishers have been saying for several seasons now: The cod really is coming back. On May 29, Dr. Sherrylynn Rowe, a Memorial University scientist aboard the research vessel Celtic Explorer, wrote a blog post describing describing the most recent measurements. “Over the last several years, we have observed extraordinary changes in cod within this area with much evidence that the stock is on the cusp of a major rebuild,” she wrote. Dr. Bettina Saier, who runs the oceans program at World Wildlife Fund Canada, agrees. “Growth has been accelerating over the last two years,” she says. “If the stock continues to grow, and if we manage it well, it will open.”

Those are two big ifs. Fishery science is not an exact science, and many researchers are afraid that cod’s rebound will lead us to “fish too hard, too soon,” Saier says. Nobody wants a repeat of what the Los Angeles Times has called a “bitter ecological fable for our time.”

Nearly everyone (government officials included) agrees that the Byzantine policies currently governing Newfoundland’s fisheries need an overhaul. But whether the players – government, scientists, offshore and inshore fishers and processors – can agree on how to do this remains to be seen. Too often these groups find themselves in a power struggle, “more concerned with dividing up the pie than in creating a bigger pie,” as Bob Verge, an economist with the Canadian Centre for Fisheries Innovation observed in a 2012 Memorial University fishery-policy meeting.

But necessity is the mother of invention. If we can’t figure out a way to harvest cod sustainably, both the fish, and Newfoundland’s fishery, could disappear forever.

The basic problem with our seafood industry – back in the 1990s, and even now – is that fish in general and cod in particular are treated as a global commodity. So we fish for quantity, not quality, and money flows out of local communities, instead of into it, because much of the harvest is shipped overseas for processing.

The offshore fishing licences issued in the 1970s were a major failure of public policy that led to the decimation of cod stocks and village fishing communities. The Individual Transferrable Quota system still favours large-scale factory trawlers, rather than small-scale fishers, and because fishers want their catch to be sold for the highest value, they will throw fish out rather than use up their quota to sell it. To make a local fishery viable, cod could be processed locally, as it is done in Iceland, which would help restore jobs to communities such as Cupids without having to catch more fish.

Tony Doyle, who is vice-president of inshore fishers at Newfoundland’s largest private union, often finds himself at odds with the big players in the offshore fishing industry. Inshore fishers are frustrated by regulations that prevent them from selling their catch directly to fellow community members, and to chefs, who would be willing to pay a premium for fish fresh off the boat. Doyle and his son could earn more money by catching less fish if the regulations changed.

“For hundreds of years my ancestors came to the wharf with fish to sell fresh from their cod traps,” Doyle says. “If somebody came by and said they wanted a codfish for their dinner, we’d gut it right there.”

In mid-May, Toronto’s Terroir Symposium founder, Arlene Stein, organized a delegation of chefs, hospitality professionals and journalists from Canada, Europe and the United States to gather in St. John’s for four days to talk about the dysfunctional policies that promote Newfoundland seafood as a commodity export, in the hopes that a frank conversation about sustainable seafood could be had. (Travel for participants, including me, was covered by Terroir, Tourism Newfoundland and the Restaurant Association of Newfoundland and Labrador.)

At times, the gathering felt like a truth and reconciliation tribunal. There were confessions of past wrongs and false accusations. Government and industry was held to account. And chefs from across the country echoed Doyle’s frustration at not being able to support local fishers by buying good-quality local seafood.

The mindset and logistics on display were reminiscent of the challenges that Ontario’s local food movement was facing a decade ago. Byzantine government policies mean the distribution channels needed to get fresh fish across the country are unreliable. Paris can get Newfoundland’s seafood faster and more easily than Montreal.

Tom Dooley, the lone representative from the Newfoundland Department of Fisheries in the room, listened to the complaints. “It’s a problem we’re aware of,” he said.

Like many of the fishers who didn’t leave the bays for St. John’s or Fort McMurray, Doyle and his son now catch snow crab for a living. That fishery, along with one for cold-water shrimp, has been Newfoundland’s redemption, both literally and figuratively: Certified sustainable by the Marine Stewardship Council, they represent a comparatively lucrative source of income for local fishers.

If all goes well, the same thing will be done for Northern cod. WWF-Canada, in conjunction with MSC, is working on a fisheries improvement project to get sustainable policies in place for the Northern cod fishery before it opens. A small project on Fogo Island now fishes cod in individual pots (to avoid catching the wrong species, or the wrong size of fish) and processes the high-quality product locally to sell at a premium to restaurants.

But getting the cod fisheries right may take on an even greater urgency because the ocean’s ecosystem is so unstable. The waters off the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador are getting warmer, which could boost the productivity and expand the range of cod and capelin, its silvery prey. That same water may soon be too warm for snow crab and cold-water shrimp. The decline in crustaceans and the rebound of cod could be yet another major change for an industry not yet ready for the shift.

Miraculously, that meeting last month did not devolve into an argument in front of the people from away, though Doyle later told me he had to bite his tongue several times. Leaning over to an offshore adversary, he adopted an avuncular, almost conspiratorial tone: “If we take care of the fish, the fish will take care of us.”