Tropical island wine" sounds more like a punchline than a suggestion from a respected sommelier. But the winemakers from the Canary Islands (a.k.a. "Spain's Hawaii") are succeeding in changing that, having found a winning formula, despite the region's many built-in hardships.

Along with its remote location – the Canaries are an archipelago off northern Africa, from where it's maddeningly hard to ship – much of the region's hilly terrain is a patchwork of desert and jutting rock and stretches of volcanic soil planted with vines that produce obscure grape varietals, such as Marmajuela and Vijariego. The last time Canary wine had any name recognition was back in Shakespeare's day, when it was called "sack." That backstory features the perfect combination of romance, history and esoterica, elevating the Canaries to the world's next hot wine region.

"For a lot of the 20 th century, it wasn't a rich region, so people didn't do a lot of wine for pleasure," says winemaker Jonatan Garcia Lima of Bodega Suertes del Marqués, a winery that exports to Canada and is commonly seen in restaurants in Montreal and Toronto. "There were 250 cellars on the islands, but most were making table wine, not wines to be exported. In the last 20 years, this started to change."

Lima explains that, particularly over the last decade, many of his colleagues have woken up to the region's tremendous potential, given its amazingly cool micro-climate – the result of a cold Atlantic current and a famous cloud formation called the "sea of clouds" that keeps the sun from cooking the old, rambling vines. Some of the grapes date back to pre-phylloxera days – the holy grail for many oenophiles who wonder what viticulture might be like today if that notorious louse hadn't demolished Europe's vineyards in the 19th century. The Canaries were spared – the upside of being so remote.

The wine being made in the Canary Islands now is a departure from tradition.

That said, the wine being made in the Canary Islands now is a departure from tradition. It's neither the table wine from the era of economic hardship under Francisco Franco, nor the wine that Falstaff quaffed, which would have been fortified, like a Madeira. The new wine culture is thoroughly modern, expressing the region's terroir, which is dominated by volcanic characteristics, said to impart salinity and earthy qualities to the wine. This is especially in vogue in Canada, largely thanks to wine writer John Szabo's recent book, Volcanic Wines: Salt, Grit and Power.

"They seem very zeitgeisty right now for a few reasons, including their long history, volcanic soils and current quality revolution," says Nate Morrell, sommelier at Toronto's Bar Isabel and Bar Raval. "They also tend to pair really well with food, because of their acidity and interesting, smoky, peppery, leafy and savoury flavours that work with spicy dishes."

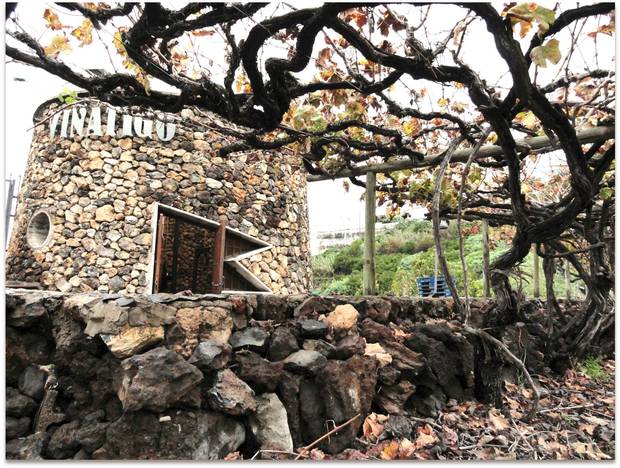

The final factor driving the new-found popularity of wine from the Canaries, which Morrell says has skyrocketed in the past six months, is the new-to-us antique grape varietals that help give it a complex flavour profile and novelty appeal. Instead of tempranillo and pinot grigio, they have gual, babosa negro and listan blanco, as well as 80-something other "extinct" varietals, that were preserved after migrating over from Spain and Portugal centuries back. Some wineries, notably Bodegas Viñátigo, are working to save these "indigenous grapes."

"Any time I sell a bottle, the reason I sell it is that it's delicious and I think it's the right wine for the guest and the food they're eating," says Morrell. "But it's always nice to have a good story. And when you can talk about these really old, untrained vines, growing almost wild, basically on a cliff overlooking the Atlantic, that's something that makes people excited about drinking it."

The outsiders

These other off-the-wine-map regions are earning kudos from in-the-know oenophiles.

Tasmania

Until recently, Tasmania's claim to fame was that it was the coolest climate in the world in which you could make pinot noir. Global warming is changing that, meaning that the region's pinot has more character, thanks to longer hang time. That boosts chardonnay and riesling, too, and might make it feasible to play around with merlot and syrah.

Baja

Many dismiss Mexico as a serious wine region on account of the heat, but with a clutch of winemakers concentrating on cool, high-altitude vineyards, opinions are starting to change. Baja California is attracting tourists from the United States seeking affordable and more casual alternatives to Napa and Sonoma.

Swartland

Given all the buzz, South African wines officially no longer qualify as hidden gems. That said, dark-horse region Swartland has recently been populated by maverick young winemakers, who are resurrecting abandoned bush vines to make wines that reflect the region's unique terroir through a strict non-interventionist philosophy of limited oak and indigenous yeasts.

Visit tgam.ca/newsletters to sign up for the Globe Style e-newsletter, your weekly digital guide to the players and trends influencing fashion, design and entertaining, plus shopping tips and inspiration for living well. And follow Globe Style on Instagram @globestyle.