The death of a Montreal woman, who was attacked by a pit bull, has brought a heated debate back into the spotlight: Should pit bull ownership be more widely banned in Canada?

The 55-year-old woman was first spotted by a neighbour, Farid Benzenati, when he arrived home from work around 5 p.m. He noticed a dog playing with “a large object” before realizing it was a woman. After yelling his neighbour’s name, Benzenati called the police and upon their arrival, the woman, who was found with several bite marks on her body, was pronounced dead at the scene. An autopsy will be conducted to determine the cause of death.

The incident followed plans announced last month by the city of Montreal to put in place a uniform set of rules regarding “dangerous dogs.” The new regulations are to be enacted for its 19 boroughs by 2018, but the city did not specify if they would include a ban of specific breeds.

But anti-pit bull advocates believe that Wednesday’s tragedy could have been prevented with a more far-reaching ban on pit bulls, as there is in Ontario.

While there are municipalities in Quebec with legislation in place, there is no provincewide ban limiting the ownership of a specific breed. Ontario has the only provincewide ban, outlawing the breeding, sale and ownership of pit bulls. This encompasses pit bull terriers, Staffordshire bull terriers, American Staffordshire terriers, American pit bull terriers and any dog with “an appearance and physical characteristics that are substantially similar” to those breeds.

The legislation was put into place in 2005 after a seven-year-old girl was killed in a pit bull attack. It has led to numerous debates, including well-known voices like American baseball player Mark Buehrle, a Toronto Blue Jays pitcher from 2013 to 2015 who could not bring his pit bulls with him to Ontario, and ultimately left the pets with his family in St. Louis.

Those against breed-specific legislation argue that all large dogs could potentially be dangerous if they are mistreated or trained badly, and the responsibility rests with owners.

“We are not taking the responsibility and we spin it and let fear drive us and try to eliminate the problem through one specific breed,” said Jessica O’Neill, a canine behaviour consultant based in Ottawa. “That does not mean that pit bulls don’t bite. It means that all dogs bite and they bite for different reasons.”

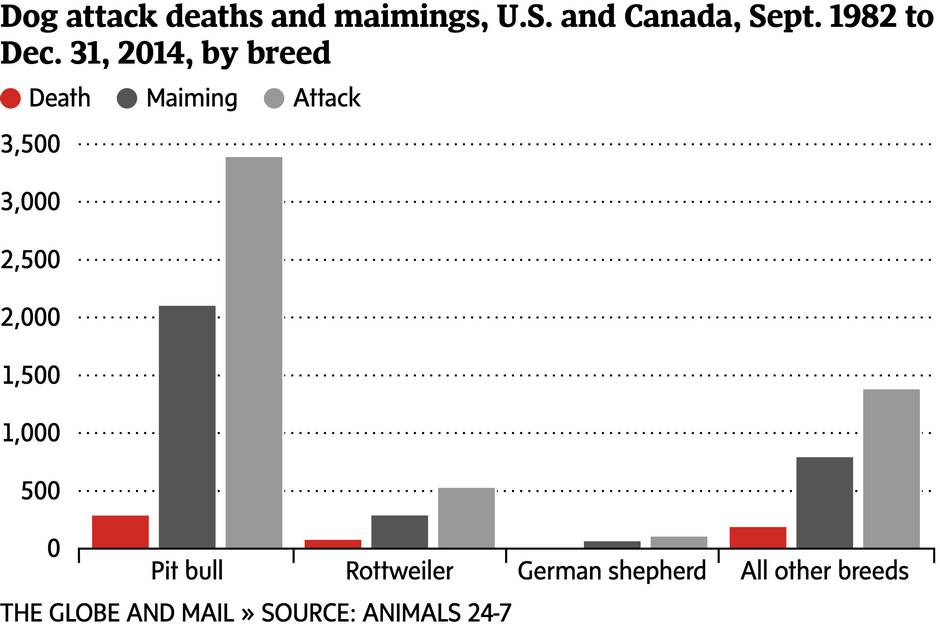

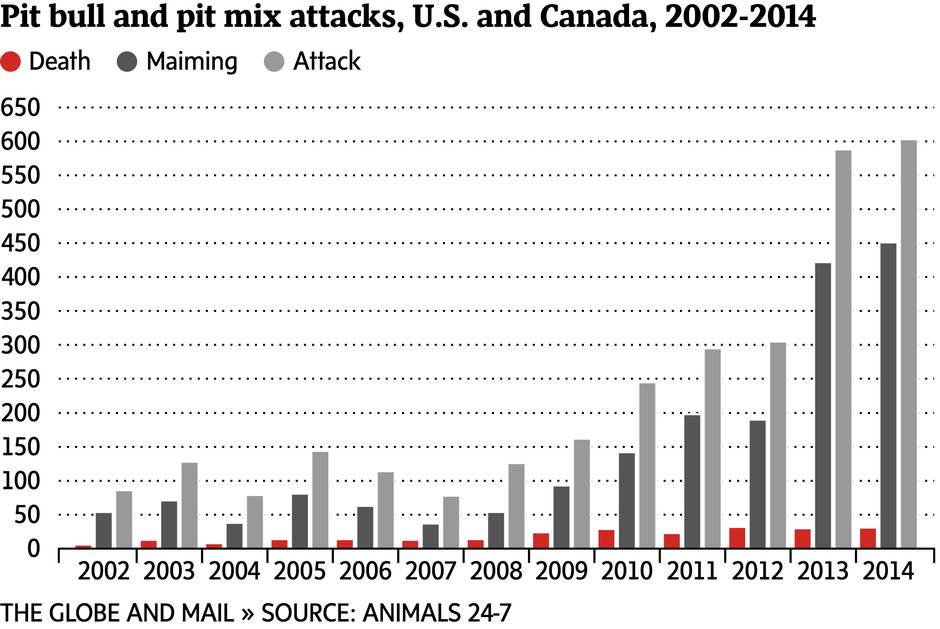

Others believe that pit bulls are uniquely dangerous, including Jeff Borchardt, founder of the non-profit Daxton’s Friends, a breed-education website. Borchardt, who is based in Wisconsin, established the organization after his son was attacked and killed by two pit bulls in 2013. The dogs, who belonged to his son’s babysitter, “never showed any signs of aggression” before that day, he said. But he noted now that “they’re the only breed that it’s recommended owners carry a break stick with. They’re used to break their jaws loose once it’s gripped onto a victim.”

Colleen Lynn, founder of DogsBite.org, a U.S. dog bite victims’ organization, said that “dramatically lowering the population of pit bulls in a community is what greatly lowers the number of attacks.”

“Do we want the pit bull population to be 6 per cent in a community or higher? I would say no, we would like them to be 1 per cent or under to avoid this,” she said.

But pit bull advocates say that despite breed-specific legislation, the number of dog bites has not significantly decreased. A 2010 Toronto Humane Society survey found no change in the number of dog bites during the years before and after the Ontario breed-specific law was put into effect.

But a decrease in the overall number of bites was never the intent of the legislation, said Borchardt, who has followed the debate in Ontario. Rather, he says, there should be a drop in “serious maimings, maulings and fatalities.”

In 2012, a study from the University of Manitoba found that there had been fewer severe dog bites in 16 urban and rural jurisdictions following Winnipeg’s breed-specific legislation banning pit bulls in 1990. But the authors did not track the proportion of bites from specific breeds.

O’Neill argued that the removal of pit bulls from a particular region does not solve the problem of aggressive dogs and will just lead to “an influx in another breed that is equally as powerful.” She said education is the key and that focusing on pit bulls is “not addressing the global problem of a lack of education, a lack of understanding, lack of regulatory legislation regarding dog ownership and the dog profession in general.”

O’Neill said there are two major problems that lead to aggressive dogs: the owner’s irresponsible behaviour or ignorance about the necessity for training and insufficient professional support. She also emphasized the importance of educating children, citing a program she’s involved with called Stop the 77, referencing the statistic that 77 per cent of dog bites are from the family dog or a friend’s dog.

After Wednesday’s incident, the Montreal SPCA released a statement on Thursday calling for new animal control bylaws to deal with dangerous dogs, but did not name a specific breed. “Veterinary associations and canine behaviourists worldwide agree that breed bans provide a false sense of security,” they wrote. “Dogs do not attack due to their appearance, but rather due to the environment in which they are raised.”

The debate over the effectiveness of breed-specific legislature is not going away any time soon, said Lynn, of DogsBite.org. “There will always be people with a great experience with their own dog.”

But “it’s not like we’re saying you can’t have a dog,” she said. “We would like for you to get one that historically for the last 35 years in this country have not been mauling and killing people at an unprecedented rate.”

With a report from The Canadian Press