A true visionary and idealistic iconoclast, Frank Lloyd Wright is universally recognized as one of the most influential architects of the 20th century. Wright spoke frequently about "an architecture for democracy." This had much to do with his belief that individuality was important and that because individuals were important they deserved spaces where their full potential would be encouraged to develop. It followed then that place making was an important ritual and that the quality of that place mattered a great deal.

Arguing America needed and deserved an indigenous architecture of its own – spaces that reflected the democratic character of American life – he turned his attention to the creation of environments that addressed the spiritual as well as the physical and social needs of the American citizen – environments to inspire, characterized by simplicity, beauty and repose. With missionary zeal, Wright promoted this radical idea in lectures, exhibitions, professional journals and fashionable home publications.

In Wright's view, Americans were living in the past – and someone else's past, at that.

While there might have been a growing interest in stylistic considerations in his time, at least among the upper classes with sufficient incomes to afford it, what Wright considered substance and spiritual character were too often overlooked. He railed against the pervasive adherence to European historic styles and formulas that no longer served the present and declared architecture in general was "significant of insignificance only" demonstrated by the "economic crimes [committed] in its name." In 1908, he publicly chastised modern American citizens for the lack of any genuine interest in their spatial surroundings, cluttering their interior spaces with superfluous decorative pieces and trying to make them fashionable, but caring little for the spiritual integrity of their environment.

"Too many houses, when they are not little stage settings or scene paintings, are mere notion stores, bazaars or junk shops ... That individuality in a building was possible for each homemaker, or desirable, seemed at that time to rise to the dignity of an idea. Even cultured men and women care so little for the spiritual integrity of their environment; except in rare cases they are not touched, they simply do not care for the matter so long as their dwellings are fashionable or as good as those of their neighbors and keep them dry and warm. A structure has no more meaning to them aesthetically than has the stable to the horse." In most of the fashionable houses of the era, Wright saw opulence without elegance or comfort and impressiveness without poetry.

Wright called his architecture "organic" and described it as that "great living creative spirit which from generation to generation, from age to age, proceeds, persists, creates, according to the nature of man and his circumstances as they both change." It was characterized by what he considered such democratic qualities as human scale, spatial freedom, integration with the site and compatibility of materials, form and method of construction. Wright's skillful implementation of these qualities resulted in spaces of soothing simplicity and restorative comfort.

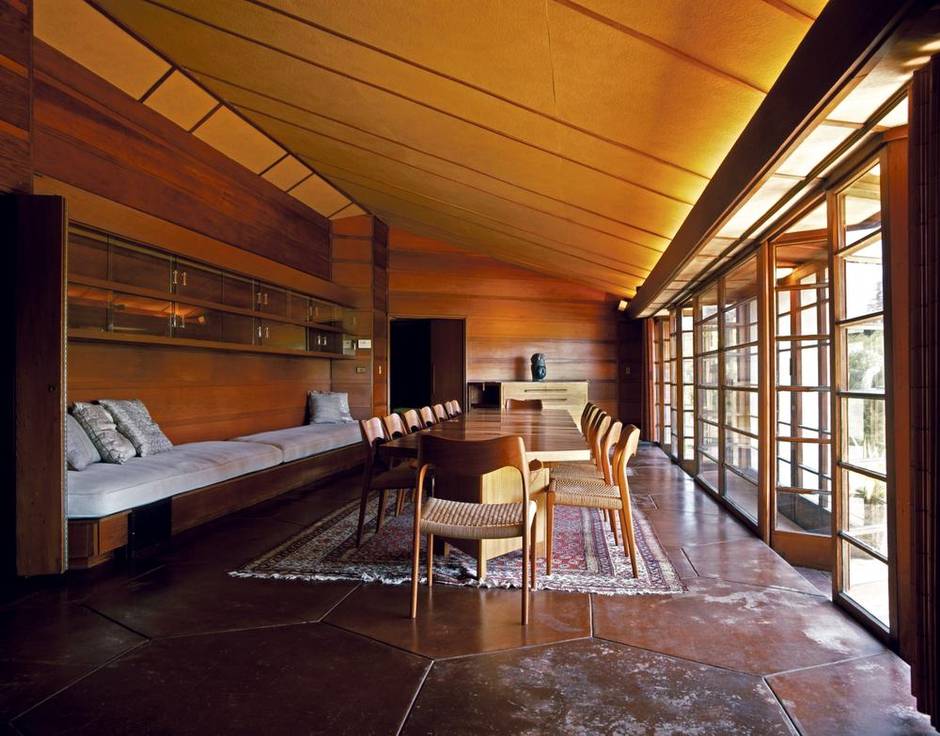

Let's eat

Frank Lloyd Wright’s appreciation for the social importance of a dedicated dining space can be seen in the layers of seating in rooms like this one at the Hanna House in Stanford, Calif. The home was one of dozens built during the architect’s Usonian era, a 20-year period when he focused on simplifying the residential form while maintaining a sense of familial comfort through the use of natural materials.

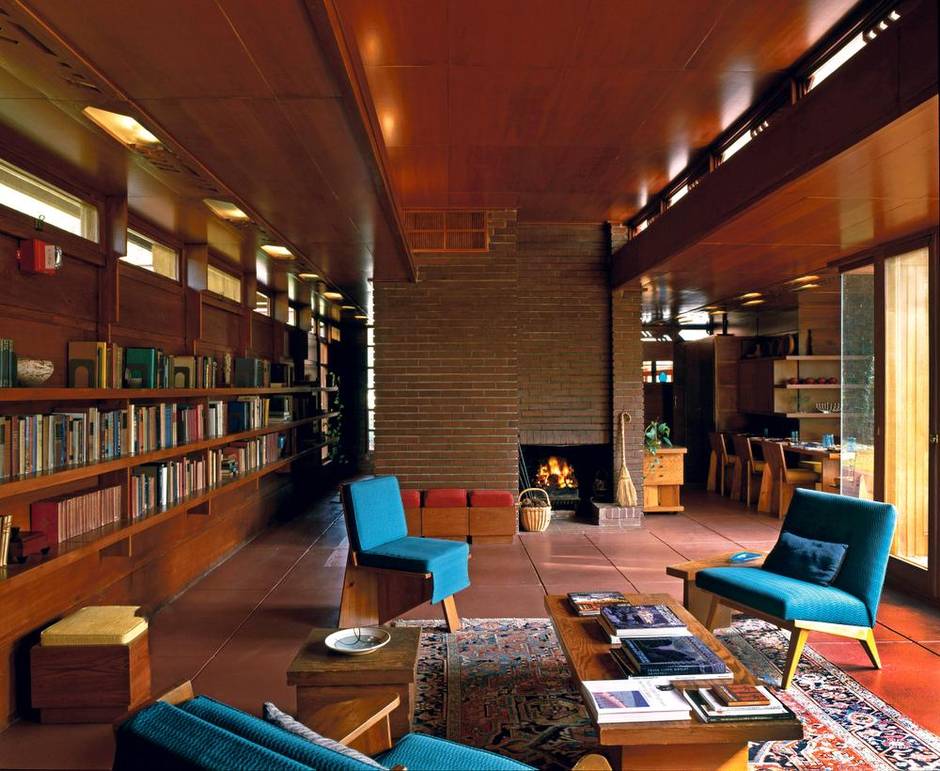

Uncommon room

The sole domicile designed by Wright in Alabama, the Rosenbaum House was an instant hit and featured in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York within a month of its completion. Like many Wright homes, it includes a central social hub – in this case, a combination living room, dining area and library – as well as doors that allowed immediate access to the outside.

Hard sell

The John Storer residence in Los Angeles is one of four structures called the Textile Block Houses. While they’re most recognized for their intricate concrete details (including the geometric walls of this bedroom), they also highlight Wright’s ability to simultaneously create a sense of interconnectivity and intimacy between private and public spaces through small changes in floor levels.

Excerpted by permission from Frank Lloyd Wright: The Rooms by Margo Stipe (Rizzoli New York, 2014). Principal photography © Alan Weintraub.

This story originally appeared in the October 2014 issue of Globe Style Advisor. To download the magazine's free iPad app, visit tgam.ca/styleadvisor.