On the occasion of the 1962 debut of the Gordon Bunshaft-designed addition to the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, the Buffalo Evening News claimed the capital of the art world had moved to upstate New York in celebration of "a bright star in its firmament." On his own visit at the time, Japanese architect Kenzo Tange called the structure "the most beautiful building in the world for an art museum."

Fifty-five years later, and poised to grow both in size and name again, the Buffalo Albright-Knox-Gundlach Art Museum is in the early throes of another renovation process that's raising eyebrows. Many locals and lovers of the clean-lined architecture style that Bunshaft helped popularize are worried that an addition by the Dutch firm Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) will compromise the modernist masterpiece. But if the project's naming donor, art collector Jeffrey Gundlach, has his way, the transformation will result in a space that rivals New York City's Whitney or Guggenheim museums – a few hours drive from a good number of Canada's art lovers.

The Albright-Knox has faced controversy before. Bunshaft, a Buffalo native and partner at mega-architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, was selected as the architect for the 1962 addition after an earlier proposal was lambasted by the press and public. Known for high-rise corporate affairs like Lever House on Park Avenue in New York City, Bunshaft lavished excessive time and energy on the Knox addition, and it shows.

His dark, glassy box, housing a 350-seat auditorium, sits atop a marble-faced enclosure that is set a respectful distance from the original 1905 neoclassical building by architect Edward B. Green. They are connected by a series of galleries and a courtyard that showcases the Albright-Knox's enviable collection of modern artworks by the likes of Josef Albers, Alberto Giacometti, Helen Frankenthaler, Jackson Pollock and Clyfford Still.

These low-ceilinged, intimate galleries were meant for more informal encounters with painting and sculpture, seen in context with other works of art. But time marches on and the needs of a gallery change. OMA and design architect Shohei Shigematsu's response to the gallery's wish list for the expansion includes underground galleries and parking, as well as turning a lot on Elmwood Avenue into park space.

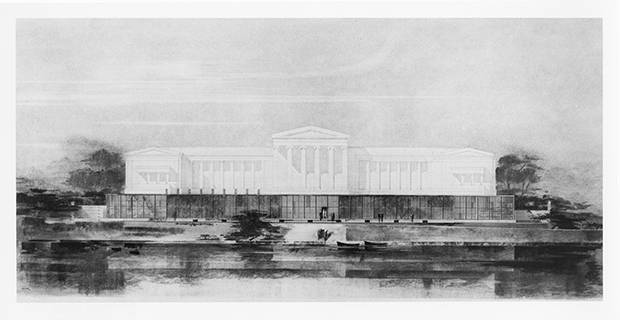

A 1957 proposal to expand the Albright-Knox (top) drew enough negative criticism to cause the gallery to abandon the scheme in favour of Gordon Bunshaft’s 1959 design (bottom).

THE ALBRIGHT-KNOX ART GALLERY

Most concerning to critics, though, is the proposal to float a box between the

Beaux-Arts and Modernist buildings, adding 13,000 square feet of exhibition space while transforming the Bunshaft courtyard and galleries into an airy but enclosed lobby with access to the Frederick Law Olmsted-designed Delaware Park and Hoyt Lake on its eastern side. While the proposal, still in its concept phase, will solve some of the challenges of the existing space, effectively doubling the number of artworks the gallery can display and giving its unassuming entrance a boost, it will also fundamentally change the scale and spirit of the Albright-Knox.

The swift backlash prompted a terse statement from gallery director Janne Sirén, who says the response is premature and the "buildings are the utilitarian tools, in some respect, that allow us to accomplish our mission." But Jorge Otero-Pailos, director of the historic preservation program at Columbia University in New York, insists they are much more than that. A proponent of an experimental form of preservation, Otero-Pailos says visitors develop attachments to museums; not just to the artwork contained within but to the buildings themselves, "because they were set up as places to represent and store what we think to be ourselves."

"Obviously, we all know that we can go on living, that we won't die without that building," he says. "But we also know that something in us will die." For this reason, Otero-Pailos recommends "subtle changes that both retain and begin to offer a different perspective; that provide experiential continuity that's somehow evolved to incorporate the realities of the present."

Line Ouellet, director of the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (MNBAQ), who oversaw the museum's own sensitive but, in the end, successful OMA-designed expansion last year thinks the Dutch architecture practice can pull it off. In the case of the MNBAQ's Pierre Lassonde pavilion, which is similarly set in a park space alongside historic structures, Ouellet says architect Shigematsu and team were able to take advantage of the natural and cultural setting, using the existing context to enrich, not unravel, the space.

"When you don't have the money, time, collection or the right talent to work on it, then you can worry, but that's not the case," says Ouellet about the Albright-Knox fracas. "For me, it's a project that I'm eager to see the result."

Visit tgam.ca/newsletters to sign up for the Globe Style e-newsletter, your weekly digital guide to the players and trends influencing fashion, design and entertaining, plus shopping tips and inspiration for living well. And follow Globe Style on Instagram @globestyle.