When part of a 13-panel art installation called Witness Blanket is revealed to the public next week by artist Carey Newman of Victoria, it will mark another healing moment for First Nations residential schools survivors and their families. Some of those families have agreed to tell their stories as they relate to personal artifacts that will be included in the art work.

John Lehmann/The Globe and Mail

Marilyn Murray

It was rarely spoken about, what happened to Marilyn Murray’s mother at St. Joseph’s Residential School in Fort Resolution, Northwest Territories. Ms. Murray did know that her mother, then Florence Dodman, had been sent there when she was about 10, along with her five siblings – after their mother, who was Gwitchin, died giving birth to her seventh child. Ms. Murray also heard about her mother’s little sister Alice. There was a day when Alice, who was seven, was very ill, but was forced to play outside nevertheless. Florence, seeing how grave her sister’s condition was, pounded on the school doors “for what seemed like forever” before someone took Alice in. “That was the last time they ever saw or heard of her,” says Ms. Murray. Efforts to find any information years later were fruitless. Then, a few years ago, Ms. Murray was watching a CBC program about the residential schools when there was a shot of that school’s graveyard. “Suddenly the camera focused in on a close-up of a grave, and there it was: ‘Alice Dodman.’ ” Ms. Murray phoned her mother. “She was sobbing. She said I can’t believe what we just saw,” she recalls. The documentary encouraged her mother to speak about her residential school experience. When Florence moved in with Marilyn a year before her death (at 86, in 2012), she brought a shoebox full of personal belongings – treasures Marilyn had never seen. Packed in the box was a pair of small caribou-hide moccasins, made by Florence’s mother and worn by each of her children who lived, before they were sent away to school. When Ms. Murray heard about the Witness Blanket, she knew the moccasins belonged with it. “It helped me through my grieving period for my mother,” said Ms. Murray, holding the little shoes, “that I could do something for her that was never spoken about until the last five years of her life.”

John Lehmann/The Globe and Mail

Newman Family

Seeking refuge in rebellion, Victor Newman, who was born in Alert Bay, B.C., was ultimately kicked out of St. Mary’s Mission and Residential School in Mission for stealing sacramental wine, which he and his friends used to drink under an apple tree. He was seven on the day he and his little brother were playing outside in New Westminster, B.C., when the priest approached. “He said ‘okay we have to take you to school,’ ” Mr. Newman, now 76 and Carey Newman’s father, recalls. Their mother was at work in the cannery, and their father was up north fishing. So the boys went inside, threw some clothing into a bag and were taken away to remote Sechelt, where the first order of business was having their hair shaved off. “Losing your hair for the first time wasn’t a very nice thing,” Mr. Newman recalls. And so for the Witness Blanket, his two daughters grew their hair for a year, then cut it off in braids as part of an eight-day ceremony this spring as their contribution to the Blanket. “It was a way to honour our dad, but a way to honour all the children ... because it was just a universal experience” says Ellen Newman, now sporting an above-the-shoulder bob. The whole family returned to Mission this year, found the orchard, and took a branch from an apple tree, which has been mounted onto a photo of little Victor and some of his siblings (two of his two sisters died alcohol-related deaths in their 20s after suffering abuse at school). Ellen says that family trip to Mission was transformational for her father, who was initially anxious. “As the day went on you could just see him getting lighter, and starting to remember things. Starting to picture where the buildings were and where his dorm was. After that I feel like he’s just been much lighter. He’s been, he’s seen it, it’s done.”

John Lehmann/The Globe and Mail

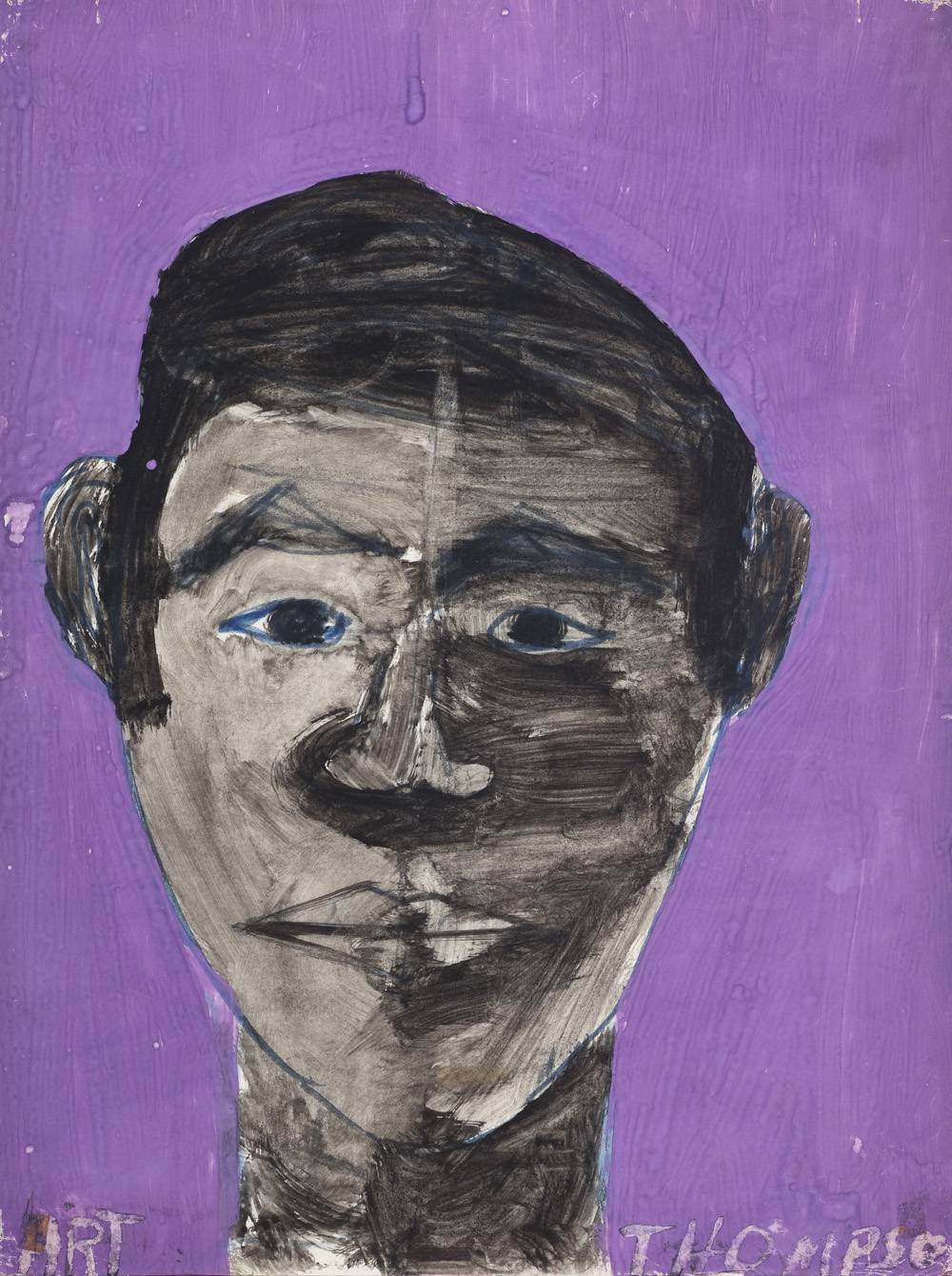

Carmen Thompson

Carmen Thompson didn’t know her father Art – residential school survivor, reconciliation pioneer, and celebrated Nuu-chah-nulth artist – until she was 12, when she met him at a relative’s funeral. But the true connection finally developed around the time she turned 17, after they hadn’t spoken in about a year, and Mr. Thompson, who was among the earliest to seek justice through the courts, gave her his victim impact statement. “I had no preparedness for what I was about to read,” says Ms. Thompson, whose mother had had a positive residential school experience. “I sat down and read it and it was mortifying.” Mr. Thompson had been taken to a TB ward when he was two, and spent three years in hospital. At five, he was sent to the Alberni Indian Residential School, where he endured horrific abuse – sexual, physical and emotional. “I heard a lot of my dad’s stories and what actually happened within those walls and I cannot fathom stability in your life after the fact,” says Ms. Thompson, now 40. There were many years of instability – alcohol and drug abuse, homelessness, estrangement from his family. His grandmother healed him back to life. And his art, says Ms. Thompson, was a sanctuary. “It was a release. It was a purging. It was something to have control of.” A few years after Mr. Thompson’s 2003 death, a painting he had made at residential school was discovered. Ms. Thompson found the image disturbing – the large, ominous face, maybe representing a perpetrator. “This piece of paper just seemed to transfer his sadness and his hurt, and I could feel it.” The work will be the only painting installed into the Witness Blanket rather than photo-transferred, following a decision by the Thompson family to donate the work to what they believe is an important project. “It’s elevating things to the forefront that need to be talked about.”