Downtown aftershocks

Building a freeway through a city has the impact of an earthquake. Neighbourhoods are changed forever, old landscapes and pathways through the city are destroyed, new ones are created.

As it turns out, the same thing happens when a city demolishes a freeway – or even part of one – as Vancouver is planning to do.

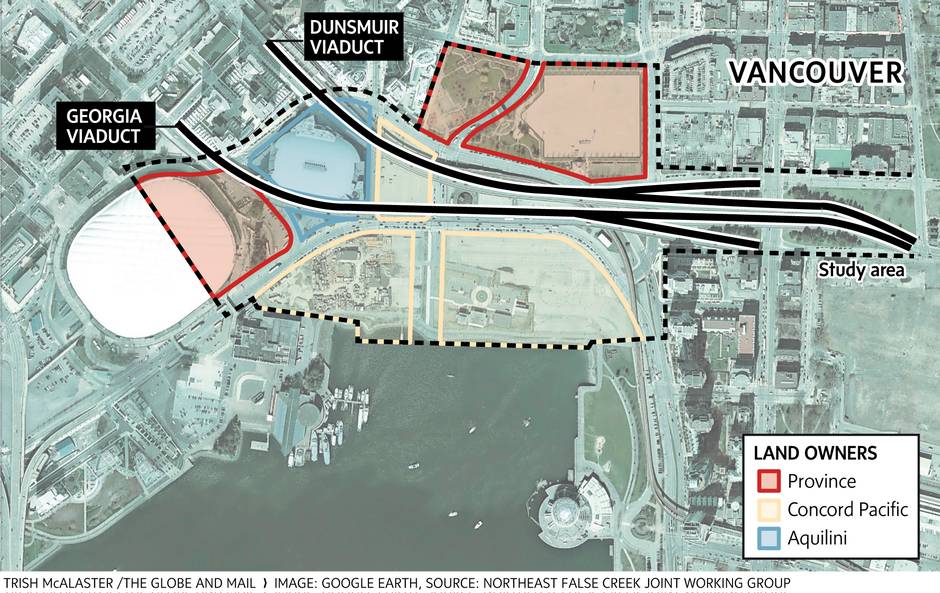

The city is preparing to take down the two 1.2-kilometre viaducts that convey vehicles smoothly off the eastern escarpment of the downtown peninsula, allowing them to fly across what used to be the mud flats and swampy end of False Creek, and then land on the higher ground of east Vancouver. The coming change has generated a lot of angst.

In the early years after the idea was first proposed in 2009, the anger was about traffic. Now it’s about what exactly will arise from this significant piece of land on the northeast shore of False Creek.

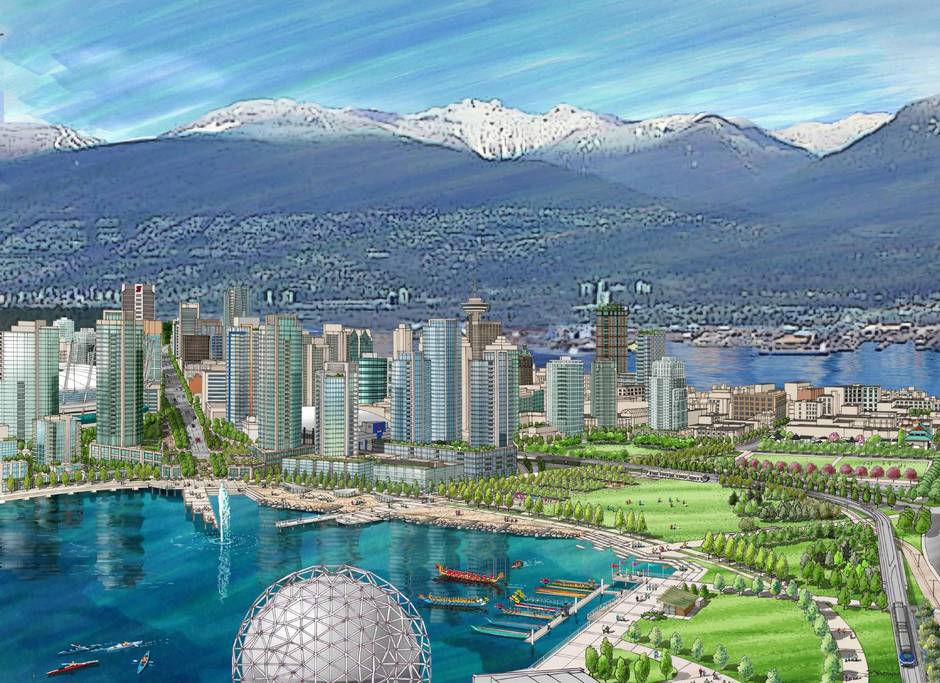

City staff have estimated the new area could see 2.5 million square feet of development. Based on recent developments in the area, that could mean as many as 3,500 new homes and 7,000 to 8,000 people, along with shops, cafés and other businesses.

Fern Jeffries, one of the most persistent critics of city and developer plans for the area, fears it will become another stuffed-to-the-gills swath of densely packed glass towers without the childcare spaces, community centre, library facilities and schools that the thousands of new residents will need.

“There’s no social infrastructure, no community building, no education strategy, nothing that has been discussed that gives us confidence,” said Ms. Jeffries. As a frequent spokeswoman for the False Creek Residents Association, she has watched the plans for the area evolve for years.

Her pessimistic view was echoed in an Insights West survey that found 71 per cent of people polled thought that taking the viaducts down would mostly benefit the landowning developers in the area – Concord Pacific being the major one – not the city’s citizens. The poll of 547 residents has a margin of error of plus or minus 4.2 percentage points.

Two Vancouver former senior planners say it’s possible to overcome that public cynicism, but they say that will only happen if city politicians change the way they’ve been handling development in recent years.

They need to get the public involved from the beginning, be open about who’s getting what, and encourage their staff to bargain hard.

Former chief planner Larry Beasley says people need to be invited to a major planning festival to generate ideas for the future neighbourhood. It also has to happen now, before the city, the province and Concord Pacific get too far down the road negotiating developer fees and provincial contributions.

“If you negotiate everything and then do the plan, that never works,” he said.

Instead, having the public participate in a large planning charrette led by good designers will give all the negotiating teams strong direction on what to trade to get the things that people seem to want most.

Mr. Beasley also said there are many possibilities to create a different-looking neighbourhood – perhaps a series of small squares surrounded by low-rise buildings, like a European city; perhaps developments with more varied materials and heights to match nearby Chinatown and Strathcona – that will get people excited about this new addition to Vancouver.

Mr. Beasley also said the city will need to be completely open about the finances and trade-offs.

“In the old days, we would let the public be a part of defining what the negotiation was going to be about. That changed in recent years. It was more behind closed doors.”

One of the planners who was Mr. Beasley’s right-hand man during negotiations with Concord Pacific in the 1990s says the city has to demonstrate it can be a tough bargainer – and it hasn’t been doing that recently.

Ralph Segal believes the viaducts should come down. When Mr. Segal was working on the 2009 plan for the area, everyone was stymied in trying to do anything creative because of the barrier those elevated roads created.

Having open land to design a new community creates many possibilities, he said. Among them is a significant chunk of housing that’s affordable, since some of the land belongs to the city.

“Yes, there will be a whole bunch of condos, 40 to 50 per cent, for the obscenely rich. But if the city negotiators have the mandate to negotiate properly, 30 to 40 per cent will be affordable.”

Mr. Segal noted though that city staff will need to be empowered to drive a hard bargain, the way they were in the ’90s and beginning of the 2000s. That’s when the city got a new seawall, parks, childcare centres, school sites, community-centre sites and much more from the developers building on old downtown industrial land at Coal Harbour and False Creek.

Mr. Segal said it’s not a given that city staff will have the backing to do that again. “I can’t predict whether Vision and Vancouver and the people who are left there to negotiate aren’t going to give up the ballpark to Concord.”

The key to what city residents will really get out of this area will be decided in the next 18 months, as a city team, Concord executives, and provincial staff negotiate over who is going to pay what and who is going to get what.

The negotiation is more complicated than it has been for any other piece of land around False Creek for several reasons. One is that the city has some land, but not complete control, as it did with the Olympic village lands on the southeast shore of False Creek.

Second, Concord won’t just be getting extra density in the new opened-up area. It will also benefit from having the viaducts come down by being able to sell the same condo for more money, once it’s overlooking a park instead of an elevated highway. That will have to be part of the financial calculation.

A third factor is that the province, as a result of the sales agreement signed more than a quarter of a century ago, will be getting money from Concord once it goes past the 12-million-square-foot mark with its developments. That is approaching. The city’s team will be working to convince the province that some or all of that money should go back into the new neighbourhood for the amenities that will make it livable.

“We have an extremely complex negotiation coming between the province, Concord and the city,” says Councillor Geoff Meggs, who has been the main champion of the viaducts removal. “The public needs to have a high degree of confidence that they’re going to get the benefits.”

Subterranean mysteries await

No one is completely certain what is under the dirt around the Vancouver viaducts.

It could be old rail cars. Bricks. For sure, there was a tar-dumping area under one part of the Concord Pacific parking lot near the company’s presentation site. A coal and coke pile existed just east of there, according to archeological investigations the city has done in preparation for removing the viaducts.

Most ominous is that there may be logs and other wood. A picture from the Vancouver Archives of the viaducts construction in 1971 shows timber pilings being driven into the ground.

“That’s the worse case if there are organics down there because they decompose and leave a void,” says Vancouver’s acting director of transportation, Lon LaClaire.

Voids can sink and collapse, taking what’s above down with them. That’s why Mr. LaClaire and his engineering team decided that dismantling the 54-year-old viaducts as soon as possible was the best thing the city could do.

“We’ve been concluding that they really have no foundation. This is a total toppling situation. The risk is that they will just fall over in an earthquake, a much more serious failure than the Burrard or Granville bridges.”

That’s just one problem with the dirt and junk that was used to fill in the northeast corner of False Creek, a place where the water use to run under the previous set of viaducts, lapping at the shore close to what is now Prior Street.

The other problem is all the soil soaked with industrial waste in this area that had blacksmiths, coal-gasification plants and fuel pipelines.

A 1992 report on the old Expo lands calculated that about 85 per cent of the fill was mostly junk and dirt, safe for recreational and residential use. About 10 per cent was safe for commercial or industrial use and just under 2 per cent was heavily contaminated.

The province has spent $68-million to date on removing or managing the debris and contaminated soil – $3-million of that in the last two years. It still has an office near the viaducts, where Pacific Place Remediation monitors runoff from the still undeveloped land to make sure no water is seeping underneath the asphalt and then leaching chemicals into False Creek.

The B.C. government will have to pay to deal with soil on its last piece of Expo ‘86 lands. There’s no price tag for that yet, but the city is estimating around $21-million for its costs on its land under the viaducts.

It came as a surprise to some residents during the viaducts debate, but engineers and soil experts say the best way to deal with that contaminated soil is to leave it where it is, capping it and putting a park on top.

“If you bury it, it’s out of the reach of the common plants,” says University of British Columbia soil scientist Les Lavkulich. “Burial is a good idea.”

Mr. LaClaire notes that trucking contaminated soil through the city, instead of burying it, creates a lot more risk.

“The very act of digging it up exposes it to the environment. Then it has to get trucked. In all those steps, it has the potential to come into contact with humans and animals.”