The most shocking elements of Hurricane Harvey in Houston were how intensely it rained, how fast the flood happened, and how relentlessly unstoppable it was. The weather seemed to live by rules of its own. The Class 4 hurricane was "downgraded" to a tropical storm Monday and to a tropical depression midweek, but the 6.6 million residents of Houston upgraded their grasp of the gravity of the disaster with every ensuing day.

Water levels in parts of the fourth-largest city in the United States rose six inches an hour. The Brazos River surged 30 feet, and the water was coming for Louisiana too: the deluge was aggressive, relented, then got worse again, like a bitter nighttime argument. Submerged, Houston's cityscape of turnpikes and malls and parking lots is smoothed out and featureless, almost prehistoric: You half expect a brontosaurus to lumber into view, munching treetops. Highway off-ramps have become rescue boat launches.

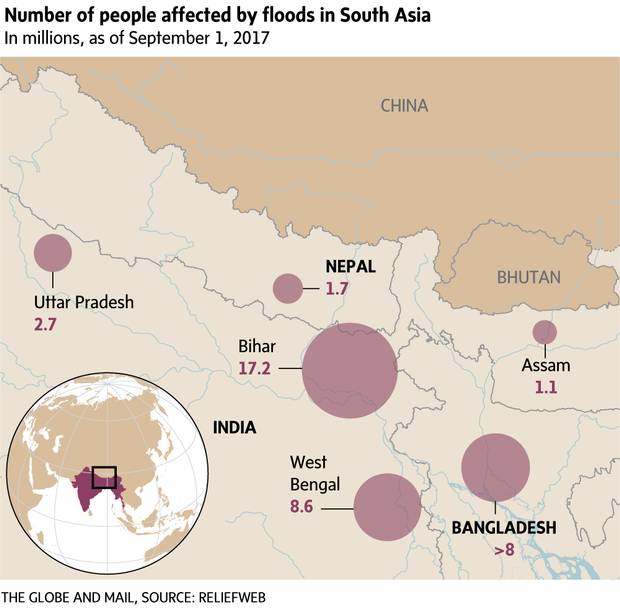

As many as 39 people are thought to have died at the time of writing, a miraculously small number (1,200 have died and millions are homeless due to current floods in India, Bangladesh and Nepal), except that rescue crews have yet to sweep the vast majority of the buildings under water, and no one knows what they will find. More than 32,000 people have taken refuge in emergency shelters; 450,000 will need federal aid to rebuild and recover. The U.S. Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) promised Houston two million meals and two million litres of water, a number that instantly seemed as inadequate as it was huge.

Rainfall from the storm was expected to top 1.3 metres – a year's worth of rain in a week, and the biggest downpour in American history, prompting various officials to classify the disaster as "an 800-year flood event" and "a 1,200-year flood event" – allegedly 57 trillion litres of rain, more than twice the volume of Hurricane Katrina, roughly two-thirds of the Red Sea, or – this is America, after all – "enough water to fill all the NFL and Division 1 college football stadiums more than 100 times over," as one sprightly television network put it. The spectacle was awash in big numbers. More than 3,500 people had been rescued by midweek, plucked from roofs and cars where some had been living for two days. Property losses will be in the double-digit billions, at best.

As the rain fell and the water rose, the economic and social future of an entire state warped and split. Somewhere between 11 and 30 per cent of Texas's vaunted refining capacity is literally underwater; gas futures hit a two-year high (there are always winners in disasters), but recovery may take a decade. The endlessly looping pictures on television revealed how quickly fates are decided, and how randomly, in a climatic crisis: a gaggle of elderly women in the living room of a retirement home, knitting as they sat in their wheelchairs and walkers up to their waists in water, were rescued; in one haunting case, a couple in their eighties and their four great-grandchildren found in a van in Greens Bayou, were not. (Some 66 per cent of U.S. flood deaths in 2014 occurred in cars.)

Blame for the flood was quickly aimed at climate change and Houston's cavalier enthusiasm for development, for paving over spongy wetlands and absorbent floodplains and then building houses on them. The most obvious fear was the terror on the surface: Where is all the water going to go, if Galveston Bay is already swollen and refusing it?

But under that question ran another prospect, unstated but more terrifying: that Houston is just a dress rehearsal for what's to come when the sea level rises, as it is guaranteed to in the next 85 years. (Nearly two metres is the optimistic scientific guess.) Imagine the chaos when Houston and Miami and New York and Boston and Toronto and Vancouver are underwater at the same time.

No wonder human societies have always been afraid of floods – deep in our bones, in our collective unconscious, throughout human history, and to this day. We know floods are coming, just as Houston did, and yet, like Houston, we cast the prospect from our minds and fail to prepare. There are more floods, and more severe floods, today, thanks to global warming, than ever before, and yet our behaviour toward them in the 21st century is just as irrational as that of our pagan ancestors, who considered them a punishment from a vengeful God. As much as we fear floods, another corner of the human psyche refuses to think about them. From an evolutionary point of view, we seem incapable of planning ahead. Why is that? Do we prefer the short term profit of the status quo? Or have we now scared ourselves too much to make a move?

We ought to fear floods, especially now. This summer, in addition to Manitoba, British Columbia, Toronto, Montreal and other places in Canada, floods were wreaking catastrophe in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Taiwan, Uruguay, Brazil, Arkansas, northern India, Honduras, the Philippines, northeast Scotland, Serbia and (just this week) Mumbai, to name just a few very wet spots. Between 1995 and 2015, 3,062 floods killed roughly 175,000 people, displaced 2.3 billion others (nearly a third of the global population), and accounted for 56 per cent of all weather-related disasters. (Famine, in second place, affected only 1.1 billion people. Fires – remember how much media space the infernos in B.C. took up this summer? – accounted for 4 per cent of weather-related crises.)

These floods are getting worse, fast. In South America alone, between 1995 and 2004, 560,000 people were affected. Between 2005 and 2014, the number rose to 2.2 million, a fourfold increase. Flash floods like the one that inundated Houston this week (the National Weather Service defines a flash flood as one that happens in under six hours) are more and more common, and deadlier. Roughly 2,100 people died in such inundations in Pakistan in 2010; by 2013, in India, the number was 6,500. By 2030, global flood losses will be worth $300-billion a year. Food supplies are already suffering. In Europe and Britain, where the surviving flood plains are no longer adequate, property losses are expected to quintuple by 2050.

The central culprit seems to be climate change. (And that's despite what human boxcar Ann Coulter tweeted midweek about Houston: "I don't believe Hurricane Harvey is God's punishment for Houston electing a lesbian mayor. But that is more credible than 'climate change.'" She did not mention the fact that Houston's current mayor, Sylvester Turner, is an African-American man, but given Ms. Coulter's political leanings, that might not have changed her tweet.) A recent study in the American Meteorological Society's Journal of Hydrometeorology revealed that between 1996 and 2014, extreme rainfall in the U.S. Northeast was 53 per cent higher than it had been in the previous 94 years. Similar patterns have occurred in the Midwest and on the Great Plains, among other places.

This August, floods claimed 13 lives in Karachi, Pakistan.

Akhtar Soomro

No scientist has openly declared that the Houston deluge was specifically caused by climate change. But a strong hypothesis is already emerging. Harvey was the worst rainstorm in American history. As with an increasing number of storms, its rain also fell in a shorter period of time, a phenomenon linked to the warming atmosphere. Oceans are heating up; the Gulf of Mexico is at least one degree Centigrade warmer now than it has been, historically. The steamier air and water supplied the overhead storm with a bottomless well of rain.

And why was Harvey stalled in one place, instead of blowing through in a few days, as happened with storms of yore? Scientists believe melting Arctic ice desalinates the ocean, which in turn confuses and redirects both ocean currents and the jet stream, resulting in more jammed and stalled weather fronts. Harvey was trapped between two such inert atmospheric bollards all week.

Meanwhile, in June, at the other end of the earth, a long-building crack in the Larsen C ice shelf in Antarctica grew more than 16 kilometres in six days; in July, the cracked portion broke off completely, calving an iceberg the size of Delaware. More than 60 per cent of Earth's freshwater is frozen in Antarctica's ice sheets. Imagine that thaw, and fear it.

We come by our terror of floods honestly. The water – maternal and evolutionary, baby! – we all slithered out of is the medium we most dread, the original pool that threatens to suck us down and back again, to devolve us. Flood myths have terrified human cultures forever.

Some of the myths are fairly eccentric. Otto Rank, a pal and later sworn enemy of Sigmund Freud's, believed the human preoccupation with flooding stemmed from the suppressed desire to pee in dreams. In the creation myths of the Chukchee, who live near the Bering Sea in easternmost Siberia, male ravens compete with females to create the world. Females give birth to fledgling ravens, whereas the envious males have to be content with creating the land out of feces and the rivers and seas from urine. (There's an entire school of scholarship devoted to the role of urine in flood myths.) The Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh, the earliest known work of literature (its last major edit took place in 1200 BC), revolves around a flood so severe that even the gods get nervous.

Nor is our preoccupation with flooding just an ancient thing. The Mississippi River's Great Flood of 1927 – also caused by wetland destruction, as in Houston 90 years later, because we never seem to learn – submerged 77,700 square kilometres across seven states under nine metres of water, rendered nearly a million people homeless, and single-handedly changed the cultural history of the United States. The official death toll at the time, according to a recent essay about the Great Flood in the Times Literary Supplement, was 246; that didn't include the corpses of African-Americans, which brought the figure over 1,000. The deluge inspired writers from William Faulkner (

As I Lay Dying, an eco-disaster novel) to W. E. B. Du Bois, and musicians from Bessie Smith to Led Zeppelin. The 1927 flood is also credited with transforming American politics: it convinced disillusioned black Americans, who had been supporters of Lincoln and therefore Republican, to switch to the Democrats. It also spurred their mass migration to Chicago from the South. Ken Kesey placed the ever-stubborn Stamper family's house on a water-threatened peninsula in Sometimes a Great Notion, and Bob Dylan built an entire pier of his career on songs about floods and levees, as a metaphor for both racism and love, most recently after Hurricane Katrina flooded New Orleans and killed 1,833 people 12 years ago this very week. "If it keep on rainin', the levee gonna break," Dylan sings on Modern Times. "Everybody saying this is a day only the Lord could make."

Which brings us to Noah. The Biblical account of the Flood in Genesis 6-9 kicks off when rowdy men, God's creation, take their own daughters for wives, thereby breaking the incest taboo. God concludes man's heart is "only evil, continually," and decides "to destroy all flesh" via a world-wide flood. The only exception is 600-year-old Noah, his wife, his three sons and their wives, and one pair of every living species on earth. Why God has to wipe out the entire world to enact his revenge on some men is never clear, but the Old Testament never does things by half: If one man is guilty, all men are guilty.

Noah packs everyone and everything into a 150-metre-long, 23-metre-wide and 14-metre-high ark he has built with his own hands from gopher wood, which is Bible talk for cypress. (Ark Encounter, a contemporary theme park that features a full-size, hand-built Noah's Ark that is the sister attraction of the Creation Museum in Williamston, Kentucky, charges $40 a head for adults and $28 for children. Then again, it's the largest timber structure in the world.) You could fit about four arks into one of the largest container freighters on the ocean today.

Once the chosen are safely inside, God opens "the windows of heaven" and raises the water level of the world by about 15 metres for 150 days. The tops of the mountains disappear, and everything not in the ark drowns and dies. The water finally subsides 10 months after it rose; only then does God promise never to do such a dastardly thing again. What a jackass! And yet Noah's first act, unctuous wiener that he is? He makes a sacrifice to God for saving his family from the Deluge. God in turn gives Noah and his offspring dominion over the land and animals. That hasn't worked out so well.

The idea that environmental catastrophes are the work of a vengeful God (or gods) has dominated human culture for more than 10,000 years. No wonder so many people think floods are out of our control, that there's very little we can do to prevent or control them. That, for instance, is a publicly stated opinion of both Mike Talbot, the former director of the Harris County Flood Control District that oversees Houston, and Russ Poppe, his successor, according to an extensive (and excellent) study of Houston's flood history published last year by the Texas Tribune and ProPublica. And it's an idea that lingers, on one form or another, even among scientists.

Once, in a coffee shop in Calgary, I met David Keith, the Canadian-born Harvard professor who has been one of the world's leading investigators of the possibility of geo-engineering a reflective chemical layer in the atmosphere, to instantly lower global warming by a degree or two. "Will it work?" I asked the professor. "Well," he said, pursing his lips, "we'd want to make sure of that. Because if we get it wrong, we could bring the ice caps down to the temperate zone very quickly." Prof. Keith has suggested we might not want to bio-engineer our way out of climate catastrophes. But the lurking warning is the same, for scientists and believers alike: this is tricky stuff, and whatever we do, our fate may be out of our hands. You can say that's just a way of supporting the status quo, and you would be right; but the source of our passivity runs deeper, into our frightened marrow.

The water in Houston has started to ebb, but the fear a flood spawns lasts an especially long time.

A House moved with during the aftermath of the Galveston flood on October 15, 1900.

Library of Congress

Wendy Best has been a lawyer in Calgary for more than 30 years. Very little intimidates her. For decades she has belonged to a brainy book club – judges, lawyers, psychiatrists. Until "the flood of the century" swamped Calgary four years ago this past June, she inhaled two novels a week. It was her lifelong habit, maybe her most private pleasure.

But ever since Calgary's Elbow River rose two metres above the main floor of her house and forced her out of her home for 10 months, she hasn't been able to read a book. Four years. Magazines, yes; newspapers, sure. Anything short that doesn't require the surrender of her immediate attention, she can manage. But she hasn't been able to read a work of fiction since the water rushed up fast and anything but imaginary from the river and then the yard and then the basement. The Calgary flood of 2005 had been called the flood of a century; no one expected the water to rise again in 2013, three times as high. She figures she has PTSD, widely acknowledged as the most common post-flood ailment. She traces it back to the first seven weeks after the flood, "when we were just kicking around, staying at a hotel, staying with friends, staying with my in-laws. We were unsettled for a very long period of time. " For nearly two months she carried her daily belongings in a Walmart bag. "All of a sudden, I couldn't concentrate."

She still can't. Because the Alberta government and the insurance industry still haven't fully resolved who should pay for what, her street still isn't rebuilt, "so you're constantly reminded of it." She started her first book in four years – Ann Patchett's This Is the Story of a Happy Marriage – this June. But June is when the river swells; June is permanently stamped on her memory as the month of catastrophe. She managed three pages in four days. Her house, too, is emptier than it used to be. "It gives you a new perspective on all the crap you accumulate, that we were saving for some purpose…We're going crap-free." That way they can't lose it again. An insurance payout of $250,000 covered half the cost of her post-flood renovation.

And now that it's over? "We just sit on the back deck, and we watch the water, and ask, 'How high is it?' That's our little weirdo thing now, instead of looking at the birds."

Even mild floods change the way people understand a landscape they've relied on. Last spring the water in Lake Ontario, fed by another stalled storm system, rose a foot and swamped 60 per cent of the Toronto Islands, the heavily populated sandbars sprinkled off the shore of downtown Toronto.

Tubular-metal lifeguard chairs were stranded metres from the shore, utterly useless. A baseball diamond was a pond. The islands were officially closed to visitors until August, and Island kids had to attend school on dry mainland. Islanders hefted 40,000 sandbags, the Sisyphean symbol of floods everywhere. A visitor who paddled out to the islands in a kayak heard an incessant nag, industrial pumps flushing floodwater back into the lake. Speaking of flushing: no one wanted to think about what was in the water. But the bird life! Astonishing. The swans and ducks didn't even move out of the way: Humans, reduced to floating, were suddenly guests in their world. It felt like some kind of revenge.

Joanna Kidd has lived on the islands more or less steadily for 51 years. She spent her summer sandbagging the Queen City Yacht Club, a hundred-year-old building. "And then the water just rose and rose and rose. It kind of wasn't an issue, and then it was. It was just relentless." The water came over the wharfs, over the boardwalk, but also up through the sand, like the devil. Her home was fine. "It's not in peoples' homes," she told me one afternoon. "But it's under peoples' homes." She worried steadily: Would the sandbags hold, would the beaches wash away? "The thing about water is, it will do what it will do. It'll go everywhere." She has been a sailor all her life, but the flood water looked different. "It might be a trick of the light, but it looks almost viscous. Really strange." But then, everything's strange when it's underwater and isn't supposed to be: The rules of predictable reality are altered. "Just the fact that roads disappear, totally disappear," Joanna said. "The park's disappeared." Pause. "Driving along and seeing carp right there beside you on the road" – two-foot-long carp at that. "A plague of carp." She too is a voracious reader, and she too hasn't been able to read a book since the water rose in May. "I think the stress makes you so tired, you don't have the energy to read. Water is such a powerful force." It's so powerful, it may be permanently altering the place she has loved as a home for half a century. "I feel like I'm watching the islands turn into a swamp." What if these changes are permanent? That's another fear. Toronto's city council has been a laggard on the issue of urban drainage, just as Houston's has.

Every flood story is different but they all have these same elements: the deluge, the surprise despite the warnings, the heroics and the tragedies, the resignation, the post-traumatic anxiety. PTSD, depression and pathological watchfulness are the most common symptoms in the aftermath, in that order. Women are more susceptible than men, children and adolescents most of all. Having to vacate a home, having it happen more than once, suffering financial loss, all make it worse. Anywhere from five to 60 per cent of flood victims are affected. Psychologists identify various coping strategies: rational problem solving, emotional coping, avoidance coping. None of these work very well. Better to try detached coping – getting down and doing what you have to do as soon as you can and as calmly as possible, without taking it personally. Sheer endurance is your best bet.

Experts consider the entire constellation of problems to be "a growing public health concern." Houston will boil up a cauldron of trauma.

The other thing everyone remembers, of course, the other common element in every flood story, in all our personal Gilgameshes, is the way people band together to help each other, creating what the writer Rebecca Solnit optimistically refers to as "a paradise built in hell." The enormous hidden capabilities of large cities surface, as do otherwise dormant Samaritan impulses. Wendy Best remembers waiters from nearby restaurants carrying free trays of food, sliders, soup, you name it, into her drenched and stricken Calgary neighbourhood. "Who wants key-lime pie?" the waiters shouted. A surprising number of flood victims did.

This is why footage and stories of people stranded on and then rescued off their cars and roofs and chimneys in Houston were so compelling, and also essential to our modern flood narrative. Those people stayed behind, for a multitude of reasons, good and bad; they tried to resist the rising tide, and became stranded. We're terrified by the prospect of being left behind by nature – of drowning, alone – and the images of the rescues, repeated again and again in the media, help sustain our irrational fantasy that we can defeat the forces of nature (forces we pissed off by abetting climate change). Which is not to say that the rescues aren't worth honouring, or that the sight of people helping one another in a crisis isn't inspiring. The day after the peak of the flood in Calgary three years ago, a Sunday, an unprecedented 300 people turned up for service at Hillhurst United Church in downtown Calgary. The Reverend John Pentland was not surprised. In a flood, he says, "you do get a sense that we are a part of Creation, not distant from or above it. And that's really humbling." There might be a sopping lesson there: The quicker we admit how fragile we are, the faster we can drop our pretense of control.

A flood is a catastrophe but also a lens, an opportunity to acknowledge that disaster is upon us. But acknowledging the truth isn't automatic. A lot of flooding is preventable, with sufficient and timely infrastructure, but the need for thoughtful development gets lost in a city's lust for more and faster money. Then the flood comes, and we see human life stripped to its essence, survival and loss and grace and courage. It's all very moving, even Biblical, for a while. Then the water evaporates and we forget and get greedy again. It's not a difficult pattern to discern.

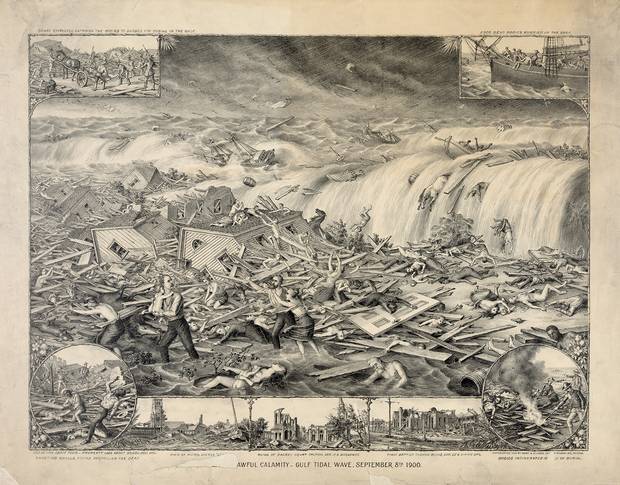

Houston is the perfect example of our willful blindness. Flooding is to Houston's history what the fur trade was to Canada, its reason for being: The city came into its own after the Great Hurricane of 1900 wiped out thriving Galveston and put inland (and presumably safer) Houston on the map.

In 1900, a hurricane swept through the town of Galveston, Texas. The deadliest natural disater in U.S. history

Library of Congress

But Houston cares more consistently about development than it does about flooding and its victims. Between 1992 and 2010, 30 per cent of the vast metropolis's water-absorbing pastureland was lost to development, while paved areas increased by 25 per cent. Water doesn't drain through concrete. The location of the concrete is even more of an issue. In June, 2001, Tropical Storm Allison poured 40 inches of water onto Houston, at a cost of more than 40 lives and $5-billion in damages. About half the buildings that flooded in 2001 were outside the city's official 100-year floodplain (the flood zone that, historically, had only a 1-per-cent chance of being equalled or exceeded in any given year). In other words, the official floodplain was already out of date in an era of rapid climate change. But since 2010, ten years after the havoc of Allison, thousands more residential and commercial buildings have been constructed on the floodplain.

Harvey is the fourth time in eight years Houstonian homes have been badly flooded. In Houston, they refer to this as "the overflow problem." People are dying because of the overflow problem.

That was the kind of short-sighted development Barack Obama sought to prevent when he signed an executive order in 2015 "establishing a federal flood risk management standard" in new public infrastructure. The new standard was designed to protect against more frequent floods due to climate change as well as a sea level rise of anywhere between eight inches and six feet by the year 2100.

Donald Trump revoked the Obama order just over two weeks ago – 10 (ten) days before Hurricane Harvey burst from the skies. Not many people noticed Mr. Trump's repeal because the press conference at which he announced it was the same one where he said white supremacists could be fine people. And he certainly didn't mention his revocation of the Obama flood protection when he popped down to Corpus Christi this week to "witness" the periphery of the Houston flood, when he said of the recovery, "we want to do it better than ever before."

This is what happens when decisions come down to money first and everything else last, when a culture prefers the glory of survival – o brave countrymen! – and the grit of recovery – this is what America's all about! – to the quiet, expensive, hard work of prevention. A few Christmases ago I took an evening boat cruise down Florida's Intracoastal Waterway near Palm Beach, the seaside winter home of billionaires and Donald Trump, among others. The cruise director kept pointing out $30-million homes whose front doors were now only a foot above the lapping water. These days the rising sea floods nearby Fort Lauderdale about twice a month, and the city recently spent $100-million on seawall reinforcements. Billionaires keep buying the watery mansions regardless: They are certain they can defeat the water, buy their way dry. Theirs was the (polar) opposite of the approach to climate I had encountered a few months earlier on a mountainside on northern Baffin Island in a 50-kilometre-an-hour wind in minus-30-degree weather. It was so cold an instant's exposure scalded your skin. I asked some locals how the Inuit had survived for 10,000 years in such brutal cold and wind and darkness. "We stay inside when it's cold and dark," someone replied, as if I had asked the stupidest question in the world. The Inuit – who confront extreme climate conditions every day – may or may not call what they face "climate change." But whatever they face, they see it as something to acknowledge, accommodate and work around.

In a 2008 paper entitled "The Conquering of Climate: discourses of fear and their resolution," a British climatologist named Mike Hulme pointed out that humans have always reacted to cataclysmic climate events through the lens of their predominant culture. Before the scientific revolution, Europeans understood bad weather in only one way, as God's punishment for our sins. A year after the Great Storm of 1703 killed at least 8,000 English, decimated the Royal Navy and felled 4,000 oak trees (it also marked the first time news bulletins of a weather calamity were sold on the street), a public ceremony was held to beg God's forgiveness. Daniel Defoe and Isaac Newton attended.

Today, six decades after scientific warnings about man-made climate change were first sounded, we still describe and therefore understand it in the language of catastrophe and endgames, as

the end of the world. (It's not the end of the world: climate change is caused globally, but its effects are local.) We occasionally test other, more sophisticated approaches – the idea of geo-engineering (mirrors around the earth), international co-operation (the Paris accord), even social engineering (everyone must drive an electric car!) – but we always revert to the hair-raising scare talk. Nearly all the footage and photographs of the floods in Houston, to say nothing of the key words used repeatedly in headlines – ravages, surreal, despair, ordeal, devastation – reinforce this trope of floods as overwhelming, unstoppable, unmanageable. Global warming is more threatening in the long run, we are often warned, than terrorism will ever be. The language and concepts we use to describe climate change never normalize it, but instead keep us scared and paralyzed, cowering blind under the bedsheets. It gets to be a habit.

"This naturally imposes the question," Hulme writes: "How will the contemporary discourse of fear about future climate change be conquered, or are we destined to remain living perpetually under the shadow of climate catastrophe?" Does our ancient habit of describing extreme climate events as disasters guarantee that they will always be just that?

It's a good question. The ironic thing is that we still take an essentially irrational, faith-based approach to the catastrophes climate dumps upon us: We wring our hands and feel bad in the midst of the crisis, and then do almost nothing and pretend the crisis doesn't exist when it abates. Maybe it's time we stopped doing that. Maybe it's time we grew up and got over our atavistic fear of flooding, of cruel Mother Water. If instead of only being terrified and hysterical we at least acknowledged floods as a permanent fixture in our lives, we'd be further ahead than simply pretending – as Houston did until last week, when it couldn't pretend any more – that the water will never get this high.

It is that high, and it's time to plan for it. Not by drowning, as the famous romantic poem by Stevie Smith does not say, but by waving.

Ian Brown is a feature writer at The Globe and Mail.

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL