The latest

- Colten Boushie’s family said they felt they were finally being heard after visiting Ottawa to press Justin Trudeau’s government for changes to the nation’s criminal justice system.

- Mr. Boushie, a 22-year-old Cree man, was fatally shot on a Saskatchewan farm in August, 2016. A white farmer, Gerald Stanley, was charged with second-degree murder, but was acquitted last Friday by a jury apparently selected to exclude people who appeared to be Indigenous.

- Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould says Indigenous under-representation on juries, and the peremptory challenges used to dismiss potential Indigenous jurors in the Stanley trial, is “definitely something that we will look into.” Here’s a primer from The Globe’s Joe Friesen about how the jury selection process works now and how Mr. Stanley could have ended up with an all-white jury.

- Earlier this week, three of Mr. Boushie’s relatives – his mother Debbie Baptiste, uncle Alvin, and cousin Jade Tootoosis – came to Ottawa to tell cabinet ministers about the injustices they say they’ve experienced.

- After his meeting with the family on Tuesday, Mr. Trudeau said he thanked Ms. Baptiste for sharing their perspective. “There’s very much a desire to work together on the path of reconciliation, on improving the system that is failing far too many Canadians,” he said.

- Mr. Trudeau was also expected Wednesday to announce the government’s plans for a new legislative framework for Indigenous people, focused on treaty rights and consultation.

Boushie’s family say they have ‘little to no faith’ in justice system

The August killing of Colten Boushie on a Saskatchewan farm has set the province on edge, igniting racial tensions.

Colten Boushie: How he died

Colten Boushie was a 22-year-old Cree man from the Red Pheasant First Nation in Saskatchewan. On Aug. 9, 2016, Mr. Boushie and his girlfriend, Kiora Wuttunee, went out for a day of swimming with three friends: Cassidy Cross-Whitstone, Eric Meechance and Belinda Jackson. On the way home, their Ford Escape hit a culvert and punctured a tire. The driver, Mr. Cross-Whitstone, pulled into a farm belonging to Gerald Stanley, a 56-year-old white man, where he and Mr. Meechance got out.

Mr. Stanley, believing they intended to steal an ATV, confronted the men with his son, Sheldon. The two jumped into the Escape and tried to drive away, but veered into Mr. Stanley's car and crashed. While Sheldon Stanley ran toward the house, Gerald Stanley grabbed a semi-automatic handgun from his shed. Firing two warning shots, Mr. Cross-Whitstone and Mr. Meechance ran off, leaving Mr. Boushie and the two women in the Escape.

Accounts differ on what happened next: Mr. Stanley testified that the gun went off accidentally when he lunged into the Escape to take the keys from the ignition, while Ms. Jackson testified that the gun was fired intentionally. Mr. Boushie was killed with a direct shot to the back of the head.

From arrest to trial to acquittal

Police charged Mr. Stanley with second-degree murder. In the days and months following Mr. Boushie's death, his family and Indigenous advocates raised questions about each stage of the police investigation and court process that ultimately led to Mr. Stanley's acquittal on Feb. 9.

Police: The night Mr. Boushie died, officers searched Mr. Boushie's family home and asked whether his distraught mother, Debbie Baptiste, had been drinking. The family filed a formal complaint, but an RCMP senior investigator's report cleared the force of any wrongdoing. The force also came under criticism for sending the Ford Escape to a towing lot five days after Mr. Boushie's death, leaving it exposed in the rain before lawyers could examine it for evidence.

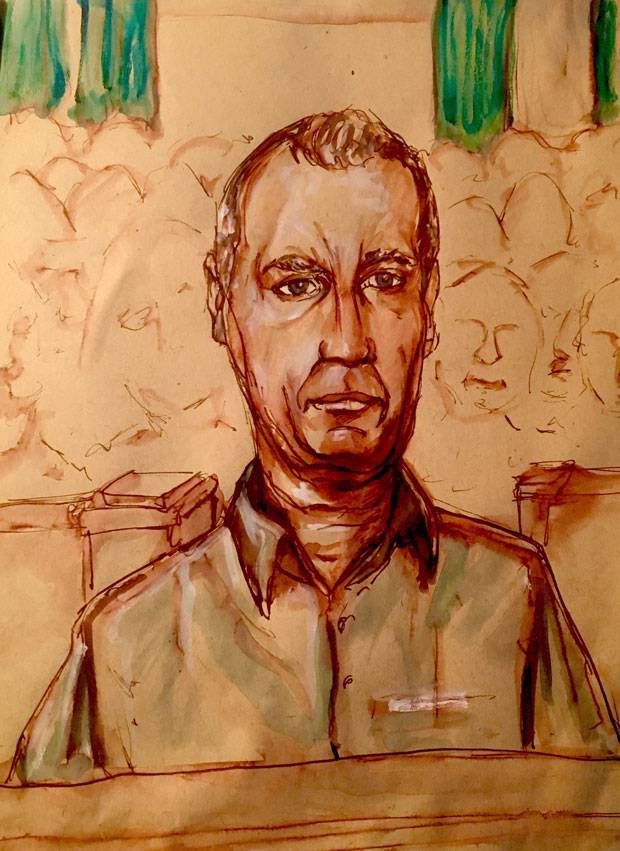

Jury selection: In January, an all-white jury, five men and seven women, was selected for Mr. Stanley's trial. One by one, the defence challenged every prospective juror who appeared to be Indigenous. This is allowed under the peremptory challenges given to defence and Crown in any criminal case; each gets 14 challenges that require no justification from either side.

Trial: The public gallery at Mr. Stanley's trial in Battleford, Sask., split along racial lines: First Nations family and friends on one side, Mr. Stanley's family and friends on the other. There, Mr. Stanley's lawyers challenged the Indigenous witnesses to the shooting, two of whom admitted they changed details of their stories after initial conversations with police. Globe and Mail reporter Joe Friesen covered the Stanley trial in January and February. Here are his reports.

- Jan. 30: RCMP left Colten Boushie vehicle in rain with door open, court told

- Jan. 31: Man accused of killing Colten Boushie only intended to scare him, son testifies

- Feb. 1: Witnesses in Gerald Stanley trial admit to changing stories since shooting of Colten Boushie

- Feb. 2: Weapon that killed Colten Boushie does not appear to have malfunctioned, court hears

- Feb. 5: Shooting death of Colten Boushie a ‘freak accident,’ Stanley defence argues in laying out its case

- Feb. 8: Gerald Stanley must be held accountable for death of Colten Boushie, Crown argues

Verdict: The jury had the option to convict Mr. Stanley of either second-degree murder or manslaughter. After 14 hours of deliberation, they acquitted him of both on Feb. 9.

Feb. 10, 2018: Colten Boushie’s uncle, Alvin Baptiste, and his brother Jace Boushie address demonstrators gathered outside of the courthouse in North Battleford, Sask.

MATT SMITH/THE CANADIAN PRESS

Feb. 10, 2018: Barbara Manitowabie lays flowers on a memorial for Colten Boushie as protesters gather in Nathan Phillips Square in Toronto to protest the acquittal of Gerald Stanley, who was charged with second-degree murder in connection with Mr. Boushie’s death.

CHRIS DONOVAN/THE CANADIAN PRESS

Beyond Boushie: Race, politics and the Stanley case

From the day of Mr. Stanley's arrest, the killing of Colten Boushie polarized Saskatchewan on issues of race, colonialism and the criminal justice system's treatment of Indigenous people. Anti-Indigenous social media messages supported Mr. Stanley's actions as vigilante justice, and then-premier Brad Wall condemned the "racist and hate-filled" comments.

But for Mr. Boushie's family and many Indigenous people in Canada, the case became symbolic of older, more widespread injustices against First Nations. The verdict was denounced by Indigenous groups including the Assembly of First Nations and Saskatchewan's Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations, which has called for an inquiry and changes to the jury-selection system.

I am calling on Prime Minister @JustinTrudeau to take immediate action to work with First Nations to overhaul the justice system. Canadians expect more and First Nations deserve far, far better. #enough #cdnpoli #JusticeForColten

— Perry Bellegarde (@perrybellegarde) February 10, 2018

In addition to pressing for an appeal, members of the family went to Ottawa the weekend after Mr. Stanley's acquittal to speak with federal cabinet ministers about broader issues of racism.

How political leaders responded

Federal government: In a rare move, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his Justice Minister commented soon after the Stanley acquittal to express their sympathy to Mr. Boushie's family. Days later, Mr. Trudeau spoke in the House of Commons about Indigenous under-representations on juries and reconciliation, saying Canada needed to do better. He met with Mr. Boushie's mother and family members in Ottawa.

’As a country, we must and we can do better’: Trudeau

Colten Boushie’s family wants ‘concrete measures’: Bennett

Federal opposition: Federal NDP leader Jagmeet Singh denounced the Stanley ruling, saying there was "no justice" in it. But Conservative Indigenous affairs critic Cathy McLeod suggested Ottawa was guilty of "political interference" for weighing in on the case.

The tragic death and pain for the family of #ColtonBoushie is unimaginable and our thoughts are with his community. We need to let the many steps of an independent judicial process unfold without political interference.

— Cathy McLeod MP (@Cathy_McLeod) February 11, 2018

There was no justice for Colten Boushie. Already Indigenous youth live with little hope for their future & today they have again been told that their lives have less value. We must confront the legacy of colonialism & genocide so They can see a brighter future for themselves.

— Jagmeet Singh (@theJagmeetSingh) February 10, 2018

Saskatchewan: Premier Scott Moe expressed sympathy for Mr. Boushie's family issued a statement advising "measured" reactions to the Stanley verdict. He said he planned to meet with Mr. Trudeau and Indigenous leaders.

What's next?

The federal Liberals say they're taking a look at Canada's policies for jury selection, including peremptory challenges. Such challenges have been eliminated in British courts, and in the United States, a 1986 court ruling allowed defence and prosecution lawyers to challenge jurors' rejections if they believed them to be racially discriminatory. Either option could make the jury selection process somewhat longer in Canada. Here's a fuller explanation from The Globe's Joe Friesen of the pros and cons of different models of jury selection.

With reports from Joe Friesen, Gloria Galloway and The Canadian Press

MORE COMMENTARY AND ANALYSIS FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL