Every crusade demands standard-bearers who will fight for the cause. Physician-assisted death is no different. Some of the families involved in the struggle to change the law spoke about what the SCC ruling means to them.

Friday was an emotional day for novelist Miriam Toews. The award-winning author, who is celebrated for her sometimes funny, often sad, but always lyrical writing, admitted she had “no words,” only “endless tears of gratitude” for the Supreme Court ruling on physician-assisted death. The court has given federal and provincial governments a year to rewrite sections of the Criminal Code to allow physician-assisted death for competent adults with “a grievous and irremediable medical condition (including an illness, disease or disability) that causes enduring suffering.”

Ms. Toews took on the Criminal Code prohibition against assisting a suicide in her autobiographical novel, All My Puny Sorrows, a book that rips the tablecloth off intractable depression and reveals the loving but intense struggle between two sisters, one who wants to die and the other who desperately tries to keep her alive.

It is too soon to say whether the decision will translate into a law that would have helped Ms. Toews and her family, but she said it is “an amazing day” nonetheless.

Jan Crowley, widow of Nagui Morcos, said the decision came too late for her husband, but she “was happy that his dying wish has been fulfilled.” Mr. Morcos was only 54 when he died, because he was determined to act before Huntington’s disease left him too incapacitated to end his own life. “Canadians with a progressive or terminal disease should have more choices than he did,” Ms. Crowley said.

Mr. Morcos, who was born in Cairo, immigrated to Canada with his family in 1967. After he watched his father die an agonizing death from Huntington disease in 1988, he discovered he had inherited the gene for the incurable neurological disease that combines elements of schizophrenia, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s. He joined Dying With Dignity as a volunteer in the campaign to change the law against assisted suicide and gave evidence in the Carter case before the Supreme Court of British Columbia. With his chorea and other symptoms worsening, Mr. Morcos began investigating ways of ending his own life before the disease destroyed him. He died on April 22, 2012, having made careful preparations so that nobody, especially his wife, could be implicated. The decision was hard on Ms. Crowley, but she knew it was what he wanted. “Because I loved him, I let him go,” she said last year.

Early Friday morning, Ms. Crowley went to the Dying With Dignity offices in Toronto to await the Supreme Court’s decision and joined an “emotionally charged and exultant press conference where there was a posse of media,” she wrote in an e-mail. “He would be so glad to know that this has happened and that he helped to change the conversation about the right to die with dignity.” Then she made her solitary way on a cold but sunny day to “keep a date with my guy” in the cemetery.

Gillian Bennett became a household name last year when the 84-year-old great-grandmother announced her own death in a blog, www.deadatnoon.com. A private person with strongly held views on end-of-life issues, Ms. Bennett had always made it clear to her family that she was going to die on her own terms and in her own time if she became physically or mentally incapacitated. And that is what she did in August, 2014, three years after being diagnosed with dementia.

Since then, her daughter Sara Bennett Fox has responded to hundreds of admiring e-mails from strangers. “I think that my Mum would have been really pleased, because she would have understood that it is a significant step in the right direction … a step towards kindness and compassion and a step away from fear and closed-mindedness,” she said.

As for her own feelings, Ms. Fox said she felt “relief and gratitude” to the many Canadians who have worked for years to decriminalize physician-assisted death and even as her “heart goes out to all who are suffering and for whom this ruling is too late.”

The decision, which “reflects the overwhelming opinion of Canadians,” is “hugely important” for people who want some measure of control during their last months of life, she said. “That could be me, it could be you, it could be my brother, it could be any of my friends, it could be my children,” she said. “I don’t want anyone I love to suffer horribly – and against his or her will – at the end of life.”

Kim Teske had a mission. She wanted to change the law against physician-assisted death and she wanted to end her own life before Huntington’s disease forced her into an institution.

In an extensive series of interviews and videos earlier this year, she and her family shared their story with readers of The Globe and Mail. Nobody knew, when Ms. Teske’s father died of testicular cancer at 42, that he was carrying the gene for Huntington’s disease. His wife, Gwen, who was 39 and had six children to raise, kept her family together through adversity and the heartbreak of learning that three of her children had inherited the HD gene. Brian, the eldest, now lives in an institution, unable to feed himself, speak clearly or walk unaided; Deanna, the youngest, is headed to a similar place and so, possibly, is one of her two adult daughters who has also tested positive.

“I love life and I love me, but I don’t want to live like that,” Ms. Teske said. For 12 days, she went without food and water until she died in May, 2014 – the only legal way she could.

“Kim will be doing the twist!” her mother responded when she heard of the Supreme Court’s decision. “I feel Kim’s choice was right and I am very proud of her. She should have waited longer, but it was her choice.”

Kim’s younger sister, Marlene Teske, agrees. “Kim would be thrilled with the decision,” she said. “She is in heaven saying ‘fabulous’ and giving us her thumbs up.”

Speaking for all the family, Marlene said she was so proud that Kim “shared her journey” with others openly. “It took a lot of courage and determination to see it through.”

Dawn Bailie, the eldest of the Teske sisters, felt as though her heart had “melted” when she heard the ruling. “Not many of us in life get to fulfill their wishes and because of Kim and her death she has created opportunities for others’ wishes to be fulfilled,” she said.

Ms. Bailie supports her sister’s “dream about choice,” but, as a nurse, she says she will “never forget that the doctors involved in upcoming cases should also have a choice” about whether to help eligible patients to die.

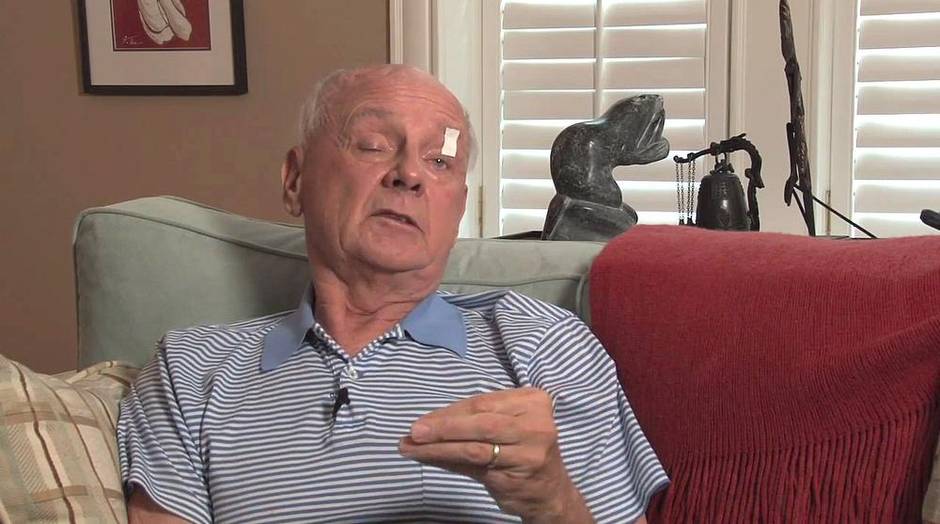

Choice was something Toronto microbiologist Donald Low wanted not only for himself but for others. Diagnosed with a malignant brain tumour, he made a video appealing to opponents of assisted suicide shortly before he died in September, 2013. “I wish they could live in my body for 24 hours and I think they would change that opinion,” he said.

Today his widow, Maureen Taylor, a physician’s assistant and a medical journalist, thinks he would have been pleased by the ruling, “even if he’d never been diagnosed with a terminal illness himself.”

As a doctor, he “was always aware that some deaths are prolonged and painful and involve weeks and even months of anxious, terrible suffering, both physical and psychological,” she said.

He might even have been a bit surprised “at how quickly this has all come about, since when he was diagnosed, just two years ago, this looked impossible.” Her own feelings are bittersweet about the unanimous decision. “It’s everything I could have hoped for, but it comes too late for the person I loved most in the world. I can’t forget how awful those months were for him. I still want to go back in time and give him a better death.”

A skeptic about politics and politicians, Ms. Taylor worries about what might happen in the political arena to the Supreme Court’s instructions to draft the necessary changes to the Criminal Code. The real heroes in the debate, she says, are those who went to court for their right to die with dignity, but she can’t minimize the role her husband played in changing medical attitudes. “I hear from physicians that Don’s video helped them come forward publicly in favour of PAD [physician-assisted death] and I’m extremely moved by that. We needed those physicians’ voices in this debate.”

Unlike so many others who took part in the debate about the right to die, Ruth Goodman wasn’t terminally ill. A social activist who had marched against the war in Vietnam and for a woman’s right to choose, she was old, tired, and beset with chronic and debilitating ailments. Like Gillian Bennett, she had talked openly for years with friends and family about her plan to end her life when she felt too worn out to continue living.

“People are allowed to choose the right time to terminate their animals’ lives and to be with them and provide assistance and comfort, right to the end. Surely, the least we can do is allow people the same right to choose how and when to end their lives,” she wrote in a suicide note made public after death at 91 in February, 2013.

Two years later, her two sons still think their mother did the right thing in ending her life on her own schedule. Michael Goodman thinks his mother would have responded, “about time,” to the Supreme Court ruling. To him, though, the decision is “far too narrow.” He thinks people “should be able to choose their time of exit, no matter what their condition” in a matter that “should be left up to them and their doctors, providing the decision and process has checks and balances.”

His brother Dean Goodman has similar views. “It’s a really good decision,” he says, “but too bad it’s only for people with terminal illnesses.” It’s a drag when the government or the court still feels it needs to be involved in this issue at all when it’s such a personal decision. I guess it’s still a number of years off before we as a society want to take this on.”

For Linda Jarrett, a 66-year-old retired French teacher from Kitchener, Ont., the Supreme Court’s ruling relieved some of the anxiety she had been feeling about her own death. Ms. Jarrett was diagnosed at age 50 with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis and uses a wheelchair. “Before [Friday’s] decision, I was left in that quandary that others before me have found themselves [in] of having to possibly hasten their own death while they were still physically capable of doing so. That is certainly something I considered looking into,” she said. “At this point in my life I’m still relatively independent, but I know that can’t remain that way with my disease for all that much longer.”

For now though, Ms. Jarrett is far from ready to die. She has two grown children, two grandkids and a third on the way. She has trips to Florida and Texas planned. Now, Ms. Jarrett has the solace of knowing that, when she is ready to die, she can ask for the help of a doctor if she wants it. “A peaceful death at the time of my choosing is now more of a reality.”

With a report from Kelly Grant