This week's election of the assembly of first nations' national chief reflects the advocacy group's fractious internal politics – much of it related to its strained relationship with Ottawa. The three men campaigning for the position are Perry Bellegarde and Ghislain Picard, two veterans of the AFN executive, and outsider Leon Jourdain.

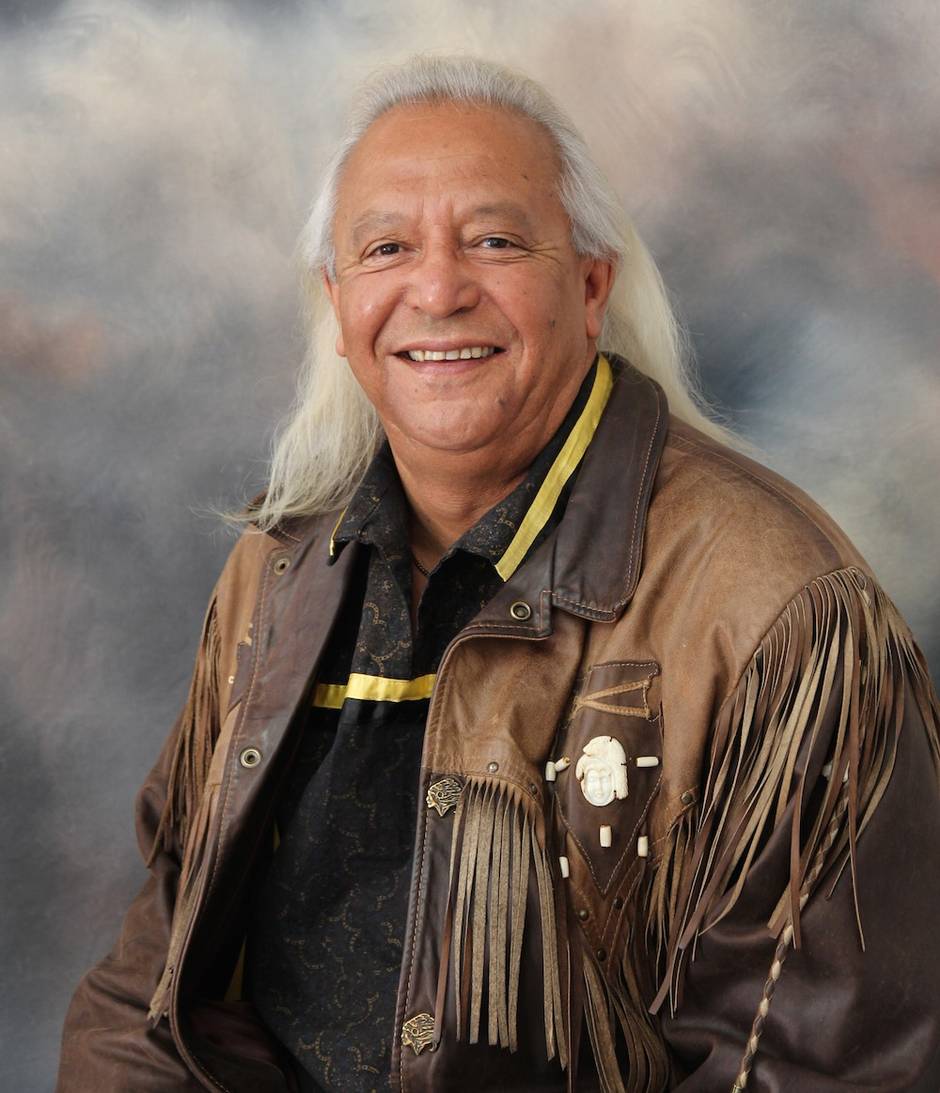

Leon Jourdain

Mr. Jourdain is a former grand chief of Anishinaabe Nation in Treaty 3 was also a councillor and chief at the Lac La Croix First Nation, at Fort Frances, Ont., for 15 years.

How should the AFN engage with the federal government?

Mr. Jourdain does not believe there is a reason for the Assembly of First Nations to engage in discussions with the government in Ottawa.

“I don’t think there is much sense in further embarrassing ourselves and putting ourselves in a position of further diminishment of our rights, our treaties, our aboriginal title,” Mr. Jourdain said.

He said he would welcome the government to the table “if they have anything meaningful to say to us.”

But individual First Nations that are part of treaties should not enter into negotiations alone, he said. Instead, he said, governments and industry are “going to deal with a collective group of people who belong to that treaty.” And where there are no treaties, Mr. Jourdain said, they “are going to deal with the collective group of people who have aboriginal titles across this country.”

First Nations are in a position of power when it comes to negotiations with governments and others, he said, because the resources that sustain the Canadian economy lie within their treaty territories.

Does the AFN need renewal and, if so, how can that be accomplished?

First Nations leaders and people across Canada are demanding change, Mr. Jourdain said.

“The leadership and the people across the country are very much saying the same thing, and that is that the national office [of the AFN] has reached a point where it must change its face, its image, and go on a different approach about how it does business with the government, particularly the sitting government,” he said.

The other candidates for national chief “are going down the same path as we have been going down for the past 40 years or so, since the birth of the AFN,” Mr. Jourdain said.

“I take the position that we have to reorganize ourselves as leaders and as people across this country, meaning that there will be no more reservation thinking. People have to be treaty-based, and it will have to be nation-based. And for those that don’t have treaties, it will be based on aboriginal title.”

Why do we need a national inquiry into missing and murdered indigenous women and girls?

Mr. Jourdain said he agrees there must be an inquiry. But, he said, the recommendations of previous inquiries on other important issues have been ignored.

“The inquiry must be controlled by us,” Mr. Jourdain said, “and we must garner some financial security to do that, so that, at the end of the day, when we learn what the findings are, we would be in control of what the next steps would be.”

Perry Bellegarde

Mr. Bellegarde is a former chief of the Chief of Little Black Bear First Nation in Saskatchewan, is the Chief of the Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations and Saskatchewan Regional Chief of the Assembly of First Nations. He was defeated on the eighth ballot when he ran for the job of National Chief against Shawn Atleo in 2009

How should the AFN engage with the federal government?

Mr. Bellegarde is the candidate who is most amenable to maintaining open lines of communication between the AFN and Ottawa.

Working relationships of the sort that exist between Canada and the First Nations are never easy, said Mr. Bellegarde, who described the existing situation as unnecessarily confrontational.

But there has to be dialogue, he said. “How else do you change people’s opinions or viewpoints other than through a respectful exchange of ideas?”

There is no question that the relationship will have to be restructured, regardless of which party is in power after the 2015 election, Mr. Bellegarde said. But “it’s still the Crown and we, as indigenous peoples, have a relationship with the Crown.”

Does the AFN need renewal and, if so, how can that be accomplished?

The schism between ordinary First Nations people and the leadership will be a challenge for the new national chief, Mr. Bellegarde said.

“It’s a matter of making sure that our AFN is relevant, responsive and respectful of that diversity, because it’s all about bringing about a change in Canada,” he said.

Some have called for all First Nations people in Canada to be able to vote for the AFN national chief, rather than the current system of an election by chiefs at an assembly. But that could turn the AFN into a form of government instead of an advocacy group, which it is now, Mr. Bellegarde said.

It may be worth a longer-term dialogue, he said. But in the short term, Mr. Bellegarde said he would look to the work of a chiefs’ committee on nation building that will also examine the AFN’s charter, and he would ask “what’s working, what isn’t working and what can we recommend to make it better.”

Why do we need a national inquiry into missing and murdered indigenous women and girls?

Education leads to awareness, which leads to understanding, which leads to action, Mr. Bellegarde said. And a national inquiry would educate Canadians about the severity of the tragedy, he said.

“Once you start talking about it, people get it, including governments,” he said. If there is an inquiry, “across Canada, there will be such a swell to change and deal with it that the government of the day cannot refuse any more.”

Ghislain Picard

Mr. Picard is Regional AFN Chief of Quebec and Labrador and was the acting national chief of the Assembly of First Nations until he announced his candidacy in September. He is an Innu from Pessamit which is located on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River.

How should the AFN engage with the federal government?

Mr. Picard said he believes there should be a line of communication between First Nations and the government, but it has to be established on native terms.

“It shouldn’t be done in a way where only government conditions prevail,” he said. “The whole relationship with government has to change, and I am not sure this government is willing to go to that extent.”

The amount of discussion and negotiation between Ottawa and the AFN cannot be decided by the national chief, Mr. Picard said. Instead, he said, it would be up to the chiefs of the First Nations across Canada to decide how far the national chief may go to advocate, promote and defend the interests of First Nations people.

The Constitution, along with treaty and aboriginal title, are the foundations for the relationship between First Nations and Ottawa, he said. And if those are not recognized, Mr. Picard said, then the government will find itself repeatedly being taken to court by First Nations chiefs.

Does the AFN need renewal and, if so, how can that be accomplished?

Mr. Picard wants to create a citizens’ forum that would allow First Nations people to express their views directly to the leaders of the AFN.

“It’s called for by the fact that the AFN of today is not the AFN of 30 years ago,” he said. “We have many more people in urban areas and certainly that changes our way of doing things.”

In the longer term, he said, a significant restructuring may be required. But at the moment, he said, many ideas are being floated about how that should be done.

“To me, one-person-one-vote is certainly very, very important to consider. But I think there are a number of questions that have to be answered,” Mr. Picard said. “There is talk of a UN-style organization. What happens to the AFN national chief then? Does he or she become a secretary-general? Personally, I don’t have any problems with that notion.”

Why do we need a national inquiry into missing and murdered aboriginal women and girls?

The chiefs, the people, and the advocacy groups that are directly touched by the tragedy have all been clear an inquiry must take place, Mr. Picard said. “And I would also suggest that, if the government is going to stand by its position not to have one, then First Nations certainly have the capacity to initiate one of their own.”