Germans go to the polls today after a campaign that failed to stir the soul inside or outside of Germany. Chancellor and Christian Democratic Union (CDU) leader Angela Merkel, seeking her fourth term, has played it safe, retaining her hold on the middle ground as she deftly pinched bits of territory from the parties on her left and right flanks.

Surprisingly, her main opponent, Martin Schulz, leader of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), played it safe too, a mystery given his superior oratory skills and desire for a surge like the one that revived the career of Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn in Britain's June election.

While the victory of Ms. Merkel's CDU and its Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union (CSU), is all but assured, surprises are not out of the question, since recent polls put about one-third of voters in the "undecided" camp. The fear among centre-right and centre-left voters is that the hard-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), the anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim party whose popularity surged during the 2015-16 refugee crisis, could end up in third spot, making it the main opposition party. If AfD's arrival would mark the appearance of the first hard-right party in the Bundestag since the 1950s, alarming Germany's liberal voting core.

But don't be lulled into thinking the election doesn't matter just because it hasn't electrified voters. Whoever wins will set the post-crisis European agenda. A German Europe or European Germany? More austerity or less? More immigrants or fewer? Whoever wins will, in effect, set the strategy for the European Union's response to Brexit and the bailout of Greece. The victor will also shoulder the responsibility of protecting Germany and the rest of the EU from the often rash and unpredictable impulses of the three alpha males on Germany's western, eastern and southern horizons – Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin and Turkey's Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Germany may not have the desire or the capabilities to assume the role of "leader of the free world," as Ms. Merkel has been dubbed in the wake of Mr. Trump's occupation of the White House. Still, that role might be thrust upon it.

Whoever forms the next German government won't be merely chancellor. He or she will have to be the leader of one of the world's last great liberal economic champions.

Easiest question first. Who is going to win the election?

Ms. Merkel and her CDU/CSU bloc conservative alliance seem to have the election in the bag, though her victory may not be as overwhelming as the polls suggest. The latest poll of polls puts the CDU/CSU on top, with 36 per cent of the vote, down about 2 points in recent weeks. Mr. Schulz's SPD is way down the charts, at about 22 per cent. At this stage in the game, the gap appears insurmountable for the SPD. Three of the four small parties – Greens, Free Democrats, Left Party – are each polling at 8 to 9 per cent while AfD is hitting 11 per cent, up from 7 per cent in August. The polls close a 6pm local time – noon Toronto time – and the first exit polls will appear within the hour. Historically, the exit polls have been pretty accurate.

But wasn't Mr. Schulz on par with Ms. Merkel only a few months ago?

Indeed, Mr. Schulz, the polyglot former president of the European Parliament, came out of the gates strong in the early spring, making it appear he would be the man who would end Ms. Merkel's 12-year reign. But he lost momentum quickly. And the SPD's defeat in two recent regional elections didn't help.

With the German economy on fire – unemployment was at a record low of 5.7 per cent in August – and Germans apparently more or less content with their lot in life, Mr. Schulz's social-justice campaign has struggled to win the imaginations of voters, young or old. He had, apparently, gambled that Jeremy Corbyn-style tactics – arguing that wages and infrastructure spending were too low, employment contracts too insecure and the tax system too unfair – would restore his popularity. It didn't work, and on other issues the SPD was not radically different from the CDU. So why vote against Ms. Merkel?

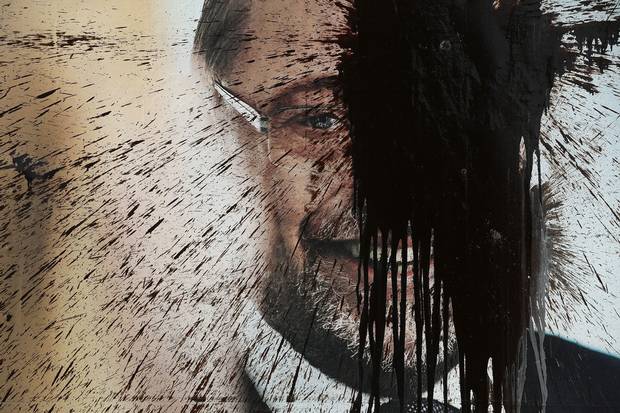

An election campaign billboard of Mr. Schulz stands vandalized on Sept. 5, 2017, in Drebkau, Germany.

SEAN GALLUP/GETTY IMAGES

Do Germany's small parties matter?

They do, all the more so since at least two of them – the Greens and the pro-business Free Democrats, led by the youthful Christian Lindner – are considered potential coalition partners in any new government. The other two small parties, The Left (whose origins are in East Germany's Communist Party), and AfD have been ruled out by Ms. Merkel as coalition contenders. But all of the small parties are expected to make it into parliament since they are polling above the 5 per cent threshold required for admission. If they do, the Bundestag will be a six-party parliament – the Free Democrats and AfD didn't make the cut in the 2013 election

What might the coalition government look like?

The make-up of the coalition is the big post-election question and negotiations to form it could take weeks, even months, and depends in good part on how many seats each party wins in the Bundestag. If the Mr. Shultz's SPD take a big blow, Ms. Merkel may try to form a coalition with the Free Democrats, or the Free Democrats and the Greens. If the SPD does well, she may try to revive the CDU/CSU coalition with the SPD that has ruled since 2013. The latter would see little change in policy direction. A coalition with the Free Democrats would put pressure on Ms. Merkel to cut taxes and regulations and take a harder stance on the Greek bailout.

Why should non-Germans care about the election?

Because Germany is the world's fourth biggest economy and Berlin is the effective driver of the European project. But the election is hardly a parochial German or European matter. If you are sitting in North America, you should care, because neither Ms. Merkel nor Mr. Schulz is a fan of Donald Trump. Relations are already strained between Ms. Merkel and the U.S. President, and if Mr. Schulz gets the chancellor's job, relations will be really strained, to the point the trans-Atlantic trade and security relationship could crumble. (When Mr. Trump was president-elect, Mr. Schulz told Der Spiegel that he "is not just a problem for the EU, but for the whole world.")

If you are sitting anywhere in the world, you should care because Germany has been a leading voice for moderation, tolerance, democracy and liberal values for decades. If voters swing to the right in the election, Germany's reputation for these values could take a hit.

Why are Germany's young voters endorsing Angela Merkel and her boring old establishment conservatives?

Elsewhere in Europe, young voters are drifting towards the underdogs or the anti-establishment parties. In the snap British election in June, they revived Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party, denying Prime Minister Theresa May her Conservative majority. In France in May, young voters backed Emmanuel Macron, the newcomer who sent the established parties packing. In Italy, the anti-establishment Five Star Movement is especially popular among the young.

Germany is a different story. There, the young are endorsing "Mutti" – Mommy – as Ms. Merkel is known. They like her unwavering liberal and democratic approach, including her "open doors" policy for refugees in 2015, and apparently see her as a bulwark against the anti-liberal, anti-environment and pro-military policies endorsed by Donald Trump. A June Forsa poll showed that 57 per cent of 18-to-21 year olds backed Ms. Merkel against only 21 per cent for Mr. Schulz.

The Germany economy is also working in favour of young voters. According to Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development figures, only 10.8 per cent of young people (20-24) in Germany were classified as NEETs – not in employment, education or training – well below the OECD and European Union average (in France, the figure is more than 20 per cent; in Italy, more than 30 per cent). In 2005, the year Ms. Merkel first became chancellor, Germany's NEET reading was 18.7 per cent.

In Finsterwalde, Germany, protesters and hecklers chant ‘Merkel must go!’ and ‘Traitor to the people!’ while holding up red slips of paper that read: ‘Red card for Merkel!’

SEAN GALLUP/GETTY IMAGES

Is the German economy an election issue?

Depends where you're standing. The German economy is on fire. Exports are soaring, the government is running a fat budget surplus and the jobless rate keeps sinking. Given all the good news, Mr. Schulz says it's time to give public- and private-sector workers hefty raises, and he's right. Germany's export success was in good part based on years of wage restraint, which made the country's manufactured goods highly competitive.

Outside of Germany, the German economy is a huge issue. Other parts of Europe partly blame Germany's huge trade and current-account surpluses (the latter happens when domestic savings exceed domestic investments) for their own economic woes, and they're right too. Higher wages would inflate the German economy, boosting domestic demand and imports from Italy, Spain and other struggling countries.

But Ms. Merkel, should she win, might be loath to change the formula that made Germany a phenomenal export success story. She has preached the virtues of austerity for everyone and there is little reason to think she will relax her stance.

Election campaign posters show Ms. Merkel and Christian Lindner, the leader of Germany’s Free Democratic Party, in Bonn, Germany.

WOLFGANG RATTAY/REUTERS

GERMAN POLITICS: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL