BRYAN GEE/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Amitha Kalaichandran is a physician and writer based in Toronto. Her first book, On Healing, will be published in 2023.

The books, I’ve realized, are the gateway drug. I thought back to the first time. It was 2010, and several friends had recommended the same one: A New Earth, by Eckhart Tolle. “You’ll hate it if you aren’t ready,” a friend said. “But trust me, if you are, then … well, boom!” She made a gesture to suggest her brain (or perhaps it was her mind) was exploding into the air. My own mind might not have exploded, but it definitely expanded – at least I thought so.

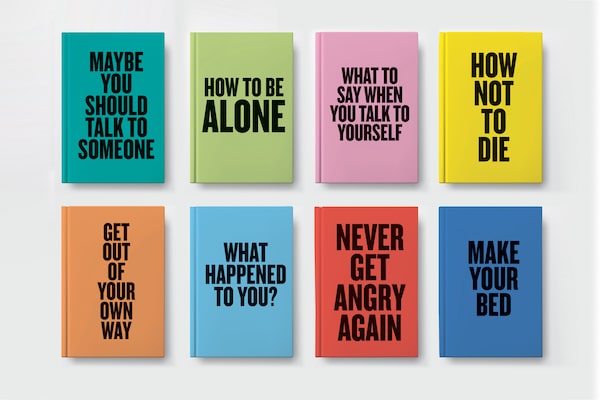

Mr. Tolle had introduced new concepts about living in the present, understanding the “pain body” that may govern our unpleasant reactions, and mindfully separating from our thoughts (that is, the monkey mind, as Buddhism teaches): all things I incorporated into my life. But then I fell into a pattern – every time I faced a challenge, from dealing with stress, to figuring out the fastest way to heal from a knee injury, to understanding how to work with difficult people, to whether a given choice was the “right” one – I’d beeline it to the bookstore and look for the now familiar sign: self-help.

I wouldn’t always leave with a book in hand. But I’d always leave a little calmer. There was something about going on a quest for an answer, to satiate the curiosity of my inner seeker, that was satisfied by perusing the book spine titles. Better, stronger, happier, smarter, fitter … improved!

Since the beginning of the pandemic, I’ve received more frequent e-mails from public relations firms all touting different online “self-improvement” workshops that the firms’ clients were offering, everything from rehabilitating a relationship that had soured while in lockdown to healthy nutrition while minimizing grocery store trips – things they hope I might write about.

Curiously, very few of the clients had a background or credentials, or even experience, in the field they were teaching. (To be sure, credentials alone don’t reflect expertise: Sometimes non-experts with experience and a track record of success can offer insights that are welcome breaks from the status quo.)

Around the same time, Instagram “recommended” that I follow an Instagram account for a “masterclass” (not to be confused with MasterClass™) course on “resilience,” seemingly taught by someone with no training or credentials in psychotherapy or coaching who had created a curriculum based on the books of Brené Brown and Esther Perel. As a final straw, a friend recently shared that she had hired an online life coach, as part of a program that included a series of videos and personal one-on-one coaching. It would cost her more than two months’ salary, but she was assured it would be worth it, even though the coach’s credentials amounted only to life experience and a smattering of testimonials. All for the sake of “improvement.”

This industry, with its promises of self-improvement with minimal credibility, reminded me a bit of the drug trade. Indeed, while these books, workshops and classes have their uses, when the demand reaches a threshold – as it did with opioids – an illicit market develops, where risks are high (the opioid crisis itself may be a response to pain, and a form of self-help as well). For self-improvement offerings, the threshold is indeed here: A mental health crisis and economic crisis, all within the context of a pandemic that has raged for two years is ripe for languishing or worse – fulminant depression and anxiety.

The natural response is to seek comfort or healing, especially if it’s easily obtained with a credit card. When it comes to self-improvement, there are researchers and credentialed professionals (many offering their courses free or for a modest fee on sites such as Coursera) who teach and offer their wisdom effectively while also having a grasp on how to offset harms. Others, like my alma mater, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, share simple, evidence-based strategies for free. Still others advise common sensical but effective approaches like social connection as part of self-care, or the salience of routines.

But there’s also another side: Fed by clickbait and newsletters selling “limited time low-priced offers” for video courses with pithy worksheets, usually by well-styled influencers, clouded in grand promises and testimonials, where a desperate individual in crisis runs the risk of being retraumatized if they are forced to recount an experience without adequate support, self-help, effectively, becoming a form of self-harm.

During this time of massive uncertainty, where many are questioning their life path, struggling with anxiety over the future, and with a deep desire for direction, the peddlers of these promises are usually the only ones who win, through recurrent payments and passive income from the desperate and vulnerable (the irony being that “financial wellness,” which is a crucial element of well-being and a social determinant of health, suffers).

The “wellness” industry in general is valued at more than US$4.5-trillion a year; the self-improvement industry (everything from apps to online coaching to seminars) was worth US$11-billion in 2017, and is now worth more than US$13-billion. This may be an underestimate now, given the fertile ground that a pandemic provides. But when it comes to the various self-improvement offerings online, there’s no data breaking down the percentage of those who offer legitimate credentials or experience versus those who are just glorified marketers. Most have a compelling story: coaching programs led by a former monk, nutrition programs by those who have “cured” themselves of a rare autoimmune disease, relationship advice from a baby boomer who (with a few simple tricks) found love again after years alone.

It goes on, sometimes ending in trauma through cult. A good story, after all, is the cornerstone of any good marketing campaign.

This all made me think back to what first brought me into that bookstore that day to thumb through A New Earth – it was low risk, in that the most I had to lose was $12.99, and I could always return the book if I wanted or if “I wasn’t ready” for the message (as my friend suggested). The promise was tempting much like a slot machine: Slip a few coins in, knowing that the chances of a windfall (and a dramatic life change) were slim but experiencing the proverbial high it offers anyway.

Because, driven by our curiosity, we’re addicted to possibility, the “what ifs” that appear not as a mirage but as something real. That, with a few pricey video courses, we are finally permitted to grasp the steering wheels of our proverbial cars and drive down an entirely different – but surely much better – road.

Recognizing that part of the drive is curiosity, we can harness it and choose our teachers wisely, and understand that much of the industry may not be legitimate but guided by a desire for profit (albeit clothed under aspirational influencer marketing). The quest to “self-improve,” is, after all, a natural part of being a human moving through the world, but when the quest for change is accelerated by troubling situations – a pandemic being the most obvious – we’re made all the more vulnerable to coy tactics.

We can also adopt a “quality improvement” approach, which is guided by formal principles, and involves defining the issue to be improved, facilitating buy-in, setting up clear goals, anticipating failures along the way, and understanding how to interpret the end result. Framing self-improvement this way might be better.

That Eckhart Tolle book might have been a gateway drug (and one I still really enjoy) but after being disappointed by flipping through other similar books, I eventually stopped searching for answers between the covers of an intriguing title. It doesn’t mean I never do, but now as a writer myself I usually look through non-fiction more for style, structure and story – never promises. In medicine, when a drug loses its effect unless more of it is given, we call it “tachyphylaxis”; at some point no amount of the drug will have an effect – which breeds addiction.

I suppose that that’s what happened with me – the high eventually wore off, but the idea might also explain why the illicit self-improvement industry has so many repeat customers.

Because while some of us stop, or might draw the line at books or podcasts, many continue to wonder if the answers still lie out there somewhere. For them, the lure to finally be “improved” never goes away. And so, while making resolutions during this uncertain time, with the allure of drastically improving our lives and our selves, some of us keep pulling the lever, allowing our hypnotized eyes and minds to reflect back those promises with glee and wonder, as we mindlessly reach for our wallets to purchase just a little more hope, even when the end goal always seems to remain just slightly out of reach.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.