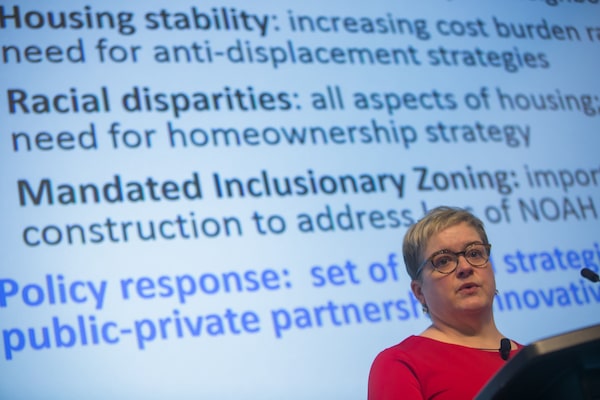

Heather Worthington, former director of long range planning with the City of Minneapolis, is working to reverse inequality in the city's housing plan.Glenn Lowson/The Globe and Mail

Heather Worthington is a consultant and the former director of long-range planning for the City of Minneapolis.

Growing up, my parents owned a single-family home in a city in Michigan. I lived within walking distance of a newly integrated school, where my Grade 2 teacher and my best friend were both Black. My parents were careful to school me in not being “prejudiced” – we were not to say the “n” word, much less talk about race. It was the beginning of the colour-blind movement in the United States; talking about race meant you were a racist.

For all their progressive talk, though, my parents moved me to a private school in third grade out of what I believe was fear – that I would make more Black friends, have more Black teachers and that more and more of our neighbours would be Black. The neighbourhood had already been affected by white flight when we left in 1979 for a small, rural farming community, where I would graduate with exactly two Black kids in my class of 250 students. The history of racial segregation is personal for white people, although we frequently ignore or marginalize both our role in racism and white supremacy, as well as the impact it has had on us.

I’ve been taking stock of this present moment of protest and reflecting on my experiences dealing with the policy foundations of racially biased land use and planning as Minneapolis’s director of long-range planning, a position I occupied for three years until this March. This moment hits especially close to home, since the recent protests in the U.S. were sparked by the death of a Black man, George Floyd, in my community.

A call for action on urbanism and race: Panelists discuss responding to anti-Black racism in cities

The words of the great American writer James Baldwin have haunted me these past weeks because they embody the mood of Minneapolis right now: “I imagine one of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, they will be forced to deal with pain." There is deep pain and there is grief. But the unrest is not as sudden or surprising as many people have said. I know from my own work, and the research produced by initiatives such as the Mapping Prejudice project at the University of Minnesota, that Minneapolis, like many other cities in North America, has a long history of racially discriminatory zoning laws and planning practices.

The long history of racially biased actions, policies, programs and institutions in North America is well known, beginning with the displacement and exploitation of Indigenous people over the course of hundreds of years, in concert with the abduction and enslavement of thousands of Black people from Africa. Even after official emancipation in the U.S. in 1863, the Jim Crow laws of the late 19th and early 20th centuries laid the groundwork for racial inequality to continue long after the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964.

After the Civil War, Black people began to migrate to the American Midwest with the hope of starting new lives free from the bonds of slavery. Many enterprising Black families settled in parts of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, buying land and establishing farms, mills and businesses.

After the First World War, Minneapolis, like many North American cities, experienced an influx of capital into land speculation. In order to maintain “desirability,” developers across North America began utilizing a legal restriction called a covenant, aimed at "protecting” the neighbourhoods they were building from the presence of Black and brown residents. These racially restrictive covenants were recorded against the property deed and were legally enforceable. If an owner sold their home to a person of colour, they could be sued and lose their financial equity in the property. The covenants led to the thorough racial segregation of the city, which persists today.

In response to the stock market crash of 1929, the federal government implemented programs that assisted home buyers with low-cost, government-underwritten loans. The administrators of these programs used what are commonly known as “redlining” maps that showed lenders where to make safe loans based on the economic wherewithal of an area and its propensity for risk. In practice, these maps were just thinly disguised tools to identify areas of a city where Black people lived. Predominantly Black neighbourhoods were deemed “hazardous” or “dangerous," thereby limiting the ability to obtain loans. Two decades later, these same maps were used by the Federal Highway Administration to plan routes for the Interstate Highway System, the result of which was an enormous loss of property in historic Black neighbourhoods through the acquisition and demolition of homes. In and around Saint Paul’s Rondo neighbourhood, the state of Minnesota expropriated hundreds of square acres of land, despite the fact that an alternate route would have affected far fewer, but whiter, neighbourhoods to the north.

Federal authorities then took the redlining practice further: They told local governments to use these maps to inform their adoption of the new regulatory tool of zoning codes. If you examine early zoning codes from most U.S. cities in the 1920s and 1930s, you will see an unmistakable pattern: Areas that were deemed hazardous or dangerous on the redlining maps are now zoned for multi-family and industrial or commercial uses; areas that were deemed desirable are now zoned for single-family uses. This was how the system ensured that Black and brown residents would be relegated to denser neighbourhoods, closer to industrial areas and without the parks, stores, schools and other amenities that white neighbourhoods enjoyed.

Redlining, racially restrictive covenants and the process for assigning single-family zoning in the city created a measurable lack of housing choice and opportunities for wealth-building for Black people and other racialized people. That’s why, in 2018, Minneapolis took the bold step of attempting to reverse its land-use limitations in the Minneapolis 2040 Comprehensive Land Use Plan.

Even with all my privilege as a white woman, I struggled to get traction with a large majority of the white community in the city when I conducted public consultations for the plan. Many times during the process, I was dumbstruck by the progressive dissonance of the community, as I came to think of it. The same white people who would attend meetings to protest the modest land-use changes we proposed – such as additional density along high-frequency transit corridors, allowing as many as three units per residential lot – also had a “Black Lives Matter” or “All Are Welcome” sign in their front yard. I once sat across the table from a white elected official who spent 45 minutes berating me for “calling her a racist” because I wanted to talk about the racial disparities in her community. In December, 2018, council voted 12-1 for our plan, which centred itself in racial equity, but it wasn’t easy; it took more than a year and the plan faced two lawsuits.

Land use and planning are part of a policy structure that forms the foundation of how people access employment, education, housing and wealth. If your family owns a home in the U.S., you are already much wealthier than many others. The Federal Reserve Bank estimated in 2016 that the median net worth of a homeowner in America was US$231,400, versus a renter’s US$5,200.

The current situation is a continuation of decades of small actions that I refer to as “box-checking." We have diversity programs, equal-opportunity hiring and lots of laws, rules and “protections,” but it still amounts to a system that incarcerates Black and brown people at far higher rates than it does white people – one that tolerates a significant gap between Black and white high-school graduation rates and policing models that tolerate a greater use of force against Black people. Mr. Floyd was a victim of that force.

The neighbourhoods that suffered most in the rioting, looting and arson that took place after the death of Mr. Floyd are among the communities that could least afford to lose those businesses, jobs and resources. They are also in the dangerous position of succumbing to the forces of gentrification and displacement that have affected many non-white communities in Minneapolis in recent years. If those businesses do not return, it will be yet another instance of disinvestment, displacement and decline for those communities. The immediate risk is that we will, once again, miss the opportunity to do the right thing – and instead focus on the politically expedient thing.

It would be easy to continue our performative response – to take a knee, say a prayer, point the finger at those “systems and institutions." But in the end, we have the ability to demand change rather than tolerate or be complicit in the oppression, injustice and bias. We are the problem and the solution. We elect the people who make these policies; we pay the police officers and urban planners. White people, including me, are responsible for changing the racist systems we created. Understanding how the very bones of cities such as Minneapolis can oppress human beings – and untangling the problems in public – is a sign of what we can achieve when we stop being afraid.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.