Family photos, Martha and Eugene wedding portrait taken in Budapest 1932 , for an upcoming Opinion section piece related to the Auschwitz concentration camp and someone’s journey there, are photographed on Dec. 21, 2023.Photographs COURTESY OF JOSEPH GONDA. COPY PHOTOS by FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Joseph Gonda recently retired after more than 50 years in the department of philosophy at York University.

The mourner’s Kaddish is one of the central prayers in Judaism. There are a number of conventions that govern its recital – it is said by immediate family members in the year following a loved one’s death; it should be recited by a minyan, or a group of 10 Jews, traditionally men; it should be said on the 10th anniversary of a loved one’s death.

My plan to say the Kaddish at Birkenau alongside my son, my only child, met none of these conventions. Yet, to the best of my knowledge no one had ever said Kaddish for my paternal grandmother Regina Frankl Gonda, who was murdered at the death camps along with many other Hungarian Jews. In my 82nd year, I felt compelled to do so.

We recited it 50 yards or so from the shambles of what I understood to be the gas-chamber complex and crematoria. It was a beautiful day and we prayed in front of a large plot of tall waving grasses, where, our guide told us, the murderers had dumped ashes, the remains of past transports, almost a century ago.

It takes roughly six hours to make the drive from Debrecen, a small city in Hungary where my widowed grandmother lived during the spring of 1944, to Oswiecim, in Poland, where the death camps operated. We know from the accounts of Hungarian survivors that it could take as many as six days to reach their final destination, packed in dark cattle cars. Did Regina know what was happening?

It had taken me almost 82 years to make the trip to Auschwitz-Birkenau. By the time I was born, in December of 1941, my parents had fled Paris, where they were living before the war, and where my father owned a small newspaper. I was born in secret – a hidden child in the taxonomy of Holocaust survival – somewhere in Vichy, France, under a false name. We remained in hiding for two years, before my parents took the fateful decision to cross by foot, over many weeks, from France into Switzerland. My mother once told me that during the final leg of their journey through the Alps, walking through woods in the middle of the night, a voice called out, “You’re going the wrong way.” My mother recounts turning around upon hearing the voice. Was it real? Was it imagined? In any event, after hearing that voice, and changing our course, my father, my mother, my sister and I eventually arrived at the Swiss border and crossed into safety.

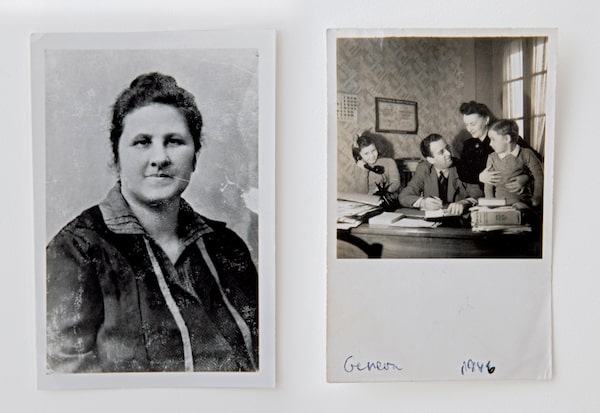

Left: Joseph Gonda’s paternal grandmother Regina Frankl Gonda is pictured in her 40s. She was murdered at the Nazi death camps along with many other Hungarian Jews. Right: The Gonda family, from left, Juliette, Eugene, Martha and Joseph are pictured in Geneva, Switzerland, in roughly 1946.Photographs COURTESY OF JOSEPH GONDA. COPY PHOTOS by FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

I first learned how Regina died within a year or so of her murder, which would have been some time in the mid-1940s. Being told of Regina’s death is a clear memory. We lived in Geneva, in a three-room apartment: ample entrance; to the left, a large kitchen, which doubled as our common room; straight ahead a small bedroom I shared with my sister – four years older than me; and to the right, my parent’s bedroom. There, sitting on their bed, I was told that my father’s mother had been done away with by Germans. We spoke French, but I have no recollection of what words were used. I assimilated the news through an image of Germans, in a civil manner, putting my grandmother into the back of a covered truck where she was put to sleep, permanently. Leaving out complications, how did this little kid know about people being put into the back of enclosed trucks by Germans and put to sleep?

I remember fleets of airplanes flying over head earlier; they must have been allied bombers on their way to Germany. My father was a journalist, at the time working for Hearst; the apartment was filled with newspapers – piles of which accompanied us to North America a few years later. Did I read something, which led me to assimilating this unwelcome news in a salutary manner? Did I already read well enough? Did I reconstruct this some time later and then predate it?

My parents never went back to the country of their birth. Their world, and almost everyone in it, was erased in the Final Solution. Instead, they moved from Geneva to New York to Washington, then back to France, where my father died. Then, my mother moved to America, for the second time, where she died just after 9/11. While she once told me the story of the guardian angel guiding us out of danger in France, we never spoke of her lost world.

My son arrived in Krakow the day before our visit to the camps. I had asked him to bring kippot, Jewish prayer caps, and copies of the Kaddish. After a sleepless night, for me, we met at dawn in the hotel lobby and took a car through the forest, to Oswiecim, where today a large, modern visitors’ centre, with the trappings of 21st-century tourism, greets you. Our driver, Pawel, instructed us, without irony, that once we made it through the security queue, we would be faced with a choice, to go left, or go right. Make sure to go right, he said.

We walked that morning through Auschwitz, which during the First World War served as a barracks for Polish soldiers. It is stately compared with the death factory at Birkenau, a few kilometres down the road. We saw glass cases filled with human hair; luggage and shoes; empty canisters of Zyklon B, the lethal gas manufactured in part by Jewish slaves down the road at Monowitz, in the factory of IG Farben, whose corporate descendants continue to operate today under names such as BASF and Bayer. We walked past a gallows where, after the war, the Allies executed camp commandant Rudolf Höss, and then through a small passageway and into the first gas chamber built by the Germans.

When we were finished, Pawel brought us lunch in the parking lot of Auschwitz: an apple; chips; again, without irony, a ham sandwich. Then we were driven to Birkenau, where we walked under the famous train tower, and beside the kilometre-long track where selections – who would live; who would die – were made and where Regina would have been pointed in the direction of the gas chamber.

The camp was a reminder of the demonic thoroughness that the Germans applied in attempting to rid the world of our people. They had undertaken extraordinary efforts to remove my widowed grandmother from her apartment in Debrecen and take her nearly 500 kilometres to Poland so they could murder her.

Kaddish is said at gravesites during funeral liturgy. It is said in shul, or synagogue. It can be said at shiva, the traditional gathering of mourners in the week after a loved ones’ death. Where would we say it at Birkenau? My son approached the guide and explained our situation. She told him about the pond, at the end of the tracks, at the back of the camp, beside a memorial. Here, she told him, survivors and their relatives sometimes say prayers. She would let us know when we arrived.

After reaching the end of the tracks, we walked past a large sculpture and turned left along a winding path past one of the four large crematoria, this one destroyed in an uprising of camp prisoners that was meticulously planned to slow the pace of murder at Birkenau, where by 1944, 12,000 Jews, mostly Hungarians, were arriving each day to be killed. Past the rubble of this crematoria were the tall grasses and the pond. The guide nodded toward my son and me, and then moved on. My son opened a leather portfolio in which he had carried from Toronto the kippot, the paper copies of the Kaddish, and photographs of Regina and other family members who were murdered by the Nazis.

We recited the prayer with trembling lips. After we finished, I looked into my son’s eyes and said, “Thank you.” The tour group stood 20 feet beyond us. My son put the kippot and the paper copies of the Kaddish away and we walked past the crematoria, back up the railway path beside the barracks and out of the camp.